Automated Tank Gauges (ATGs) are nifty bits of tech, sitting unseen in just about every gas station. They keep track of fuel levels, temperature, and other bits of information, and sometimes get tied into the automated systems at the station. The problem, is that a bunch of these devices are listening to port 10001 on the Internet, and some of them appear to be misconfigured. How many? Let’s start with the easier question, how many IPs have port 10001 open? Masscan is one of the best tools for this, and [RoseSecurity] found over 85,000 listening devices. An open port is just the start. How many of those respond to connections with the string In-Tank Inventory Reports? Shodan reports 11,113 IPs as of August of this year. [RoseSecurity] wrote a simple Python script that checked each of those listening IPs came up with a matching number of devices. The scary bit is that this check was done by sending a Get In-Tank Inventory Report command, and checking for a good response. It seems like that’s 11K systems, connected to the internet, with no authentication. What could possibly go wrong? Continue reading “This Week In Security: 11,000 Gas Stations, TrustZone Hacks Kernel, And Unexpected Fuzzing Finds”

This Week in Security292 Articles

This Week In Security: One-click, UPnP, Mainframes, And Exploring The Fog

A couple weeks ago we talked about in-app browsers, and the potential privacy issues when opening content in them. This week Microsoft reveals the other side of that security coin — JavaScript on a visited website may be able to interact with the JS embedded in the app browser. The vulnerability chain starts with a link handler published to Android, where any https://m.tiktok[.]com/redirect links automatically open in the TikTok app. The problem here is that this does trigger a redirect, and app-internal deeplinks aren’t filtered out. One of these internal schemes has the effect of loading an arbitrary page in the app webview, and while there is a filter that should prevent loading untrusted hosts, it can be bypassed with a pair of arguments included in the URI call.

Once an arbitrary page is loaded, the biggest problem shows up. The JavaScript that runs in the app browser exposes 70+ methods to JS running on the page. If this is untrusted code, it gives away the figurative keys to the kingdom, as an auth token can be accessed for the current user. Account modification, private video access, and video upload are all accessible. Thankfully the problem was fixed back in March, less than a month after private disclosure. Still, a one-click account hijack is nothing to sneeze at. Thankfully this one didn’t escape from the lab before it was fixed.

UPnP Strikes Again

It’s not an exaggeration to say that Universal Plug and Play (UPnP) may have been the most dangerous feature to be included in routers with the possible exception of open-by-default WiFi. QNAP has issued yet another advisory of ransomware targeting their devices, and once again UPnP is the culprit. Photo Station is the vulnerable app, and it has to be exposed to the internet to get pwned. And what does UPnP do? Exposes apps to the internet without user interaction. And QNAP, in their efforts to make their NAS products more usable, included UPnP support, maybe by default on some models. If you have a QNAP device (or even if you don’t), make sure UPnP is disabled on your router, turn off all port forwarding unless you’re absolutely sure you know what you’re doing, and use Wireguard for remote access. Continue reading “This Week In Security: One-click, UPnP, Mainframes, And Exploring The Fog”

This Week In Security: Malicious Clipboards, Snakes On A Domain, And Binary Golf

There’s a bit of a panic regarding Chromium, Google Chrome, the system clipboard, and of all things, Google Doodles on the New Tab Page. It’s all about Chromium issue 1334203, “NewTabPageDoodleShareDialogFocusTest.All test fails when user gesture is enforced”. You see, Chromium has quite a large regression test suite, and Google engineers want to ensure that the Google Doodles always work. A security feature added to the clipboard handling API happened to break a Doodles test, so to fix the Doodle, the security feature was partially reverted. The now-missing feature? Requiring user interaction before a page can read or write to the clipboard.

Now you understand why there’s been a bit of a panic — yes, that sounds really bad. Pages arbitrarily reading from your clipboard is downright malicious and dangerous. And if no interaction is required, then any page can do so, right? No, not quite. So, Chrome has a set of protections, that there are certain things that a page cannot do if the user has not interacted with the page. You might see this at play in Discord when trying to refresh a page containing a video call. “Click anywhere on this page to enable video.” It’s intended to prevent annoying auto-play videos and other irritating page behavior. And most importantly, it’s *not* the only protection against a page reading your clipboard contents. See for yourself. Reading the clipboard is a site permission, just like accessing your camera or mic.

Now it’s true that a site could potentially *write* to the clipboard, and use this to try to be malicious. For example, writing rm -rf / on a site that claims to be showing off Linux command line tips. But that’s always been the case. It’s why you should always paste into a simple text editor, and not straight into the console from a site. So, really, no panic is necessary. The Chromium devs tried to roll out a slightly more aggressive security measure, and found it broke something unrelated, so partially rolled it back. The sky is not falling.

Continue reading “This Week In Security: Malicious Clipboards, Snakes On A Domain, And Binary Golf”

This Week In Security: In Mudge We Trust, Don’t Trust That App Browser, And Firefox At Pwn2Own

There’s yet another brouhaha forming over Twitter, but this time around it’s a security researcher making noise instead of an eccentric billionaire. [Peiter Zatko] worked as Twitter’s security chief for just over a year, from November 2020 through January 2022. You may know Zatko better as [Mudge], a renowned security researcher, who literally wrote the book on buffer overflows. He was a member at L0pht Heavy Industries, worked at DARPA and Google, and was brought on at Twitter in response to the July 2020 hack that saw many brand accounts running Bitcoin scans.

Mudge was terminated at Twitter January 2022, and it seems he immediately started putting together a whistleblower complaint. You can access his complaint packet on archive.org, with whistleblower_disclosure.pdf (PDF, and mirror) being the primary document. There are some interesting tidbits in here, like the real answer to how many spam bots are on Twitter: “We don’t really know.” The very public claim that “…<5% of reported mDAU for the quarter are spam accounts” is a bit of a handwave, as the monetizable Daily Active Users count is essentially defined as active accounts that are not bots. Perhaps Mr. Musk has a more legitimate complaint than was previously thought.

Continue reading “This Week In Security: In Mudge We Trust, Don’t Trust That App Browser, And Firefox At Pwn2Own”

This Week In Security: Secure Boot Bypass, Attack On Titan M, KASLR Weakness

It’s debatable just how useful Secure Boot is for end users, but now there’s yet another issue with Secure Boot, or more specifically, a trio of signed bootloaders. Researchers at Eclypsium have identified problems in the Eurosoft, CryptoPro, and New Horizon bootloaders. In the first two cases, a way-too-flexible UEFI shell allows raw memory access. A startup script doesn’t have to be signed, and can easily manipulate the boot process at will. The last issue is in the New Horizon Datasys product, which disables any signature checking for the rest of the boot process — while still reporting that secure boot is enabled. It’s unclear if this requires a config option, or is just totally broken by default.

The real issue is that if malware or an attacker can get write access to the EFI partition, one of these signed bootloaders can be added to the boot chain, along with some nasty payload, and the OS that eventually gets booted still sees Secure Boot enabled. It’s the perfect vehicle for really stealthy infections, similar to CosmicStrand, the malicious firmware we covered a few weeks ago.

Continue reading “This Week In Security: Secure Boot Bypass, Attack On Titan M, KASLR Weakness”

This Week In Security: Breaches, ÆPIC, SQUIP, And Symbols

So you may have gotten a Slack password reset prompt. Something like half a percent of Slack’s userbase had their password hash potentially exposed due to an odd bug. When sending shared invitation links, the password hash was sent to other members of the workspace. It’s a bit hard to work out how this exact problem happened, as password hashes shouldn’t ever be sent to users like this. My guess is that other users got a state update packet when the link was created, and a logic error in the code resulted in too much state information being sent.

The evidence suggests that the first person to catch the bug was a researcher who disclosed the problem mid-July. Slack seems to use a sane password policy, only storing hashed, salted passwords. That may sound like a breakfast recipe, but just means that when you type your password in to log in to slack, the password goes through a one-way cryptographic hash, and the results of the hash are stored. Salting is the addition of extra data, to make a precomputation attack impractical. Slack stated that even if this bug was used to capture these hashes, they cannot be used to directly authenticate as an affected user. The normal advice about turning on 2-factor authentication still applies, as an extra guard against misuse of leaked information. Continue reading “This Week In Security: Breaches, ÆPIC, SQUIP, And Symbols”

This Week In Security: Symbiote Research And Detection, Routing Hijacks, Bruggling, And More

Last week we covered the Symbiote Rootkit, based on the excellent work by Blackberry, Intezer, and Cyber Geeks. This particular piece of malware takes some particularly clever and devious steps to hide. It uses an LD_PRELOAD to interfere with system libraries on-the-fly, hiding certain files, processes, ports, and even traffic from users and detection tools. Read last week’s column and the source articles linked there for the details.

There is a general technique for detecting rootkits, where a tool creates a file or process that mimics the elements of the rootkit, and then checks whether any of the fakes mysteriously disappear. In reading about Symbiote, I looked for tooling that we could recommend, that uses this technique to check for infections. Coming up short, I dusted my security researcher hat off, and got to work. A very helpful pointer from Intezer led me to MalwareBazaar’s page on Symbiote. Do note, that page hosts live malware samples. Don’t download lightly.

This brings us to the first big problem we need to address. How do you handle malware without getting your machine and wider network infected? Virtualization can be a big part of the answer here. It’s a really big leap for malware to infect a virtual machine, and then jump the gap to infect the host. A bit of careful setup can make that even safer. First, use a different OS or distro for your VM host and research client. Sophisticated malware tends to be very targeted, and it’s unlikely that a given sample will have support for two different distros baked in. The bare-metal host is an up-to-date install for best security, but what about the victim?

While we want a bulletproof foundation, our research VM needs to be vulnerable. If the malware is targeted at a specific kernel version or library, we need that exact version to even get started. Unfortunately the samples at MalwareBazaar don’t include details on the machine where they were found, but they do come with links off to other analysis tools, like Intezer Analyze. One particular embedded string caught my eye: GCC: (GNU) 4.4.7 20120313 (Red Hat 4.4.7-17) That’s likely from the machine where this particular Symbiote sample was compiled, and it seems like a good starting point. GCC 4.4.7-17 shipped with Red Hat Enterprise Linux version 6.8. So we grab a CentOS 6.8 live DVD ISO, and get it booting on our VM host.

The next step is to download the malware samples directly from MalwareBazaar. They come in encrypted zips, just to make it harder to accidentally infect yourself. We don’t want those to land anywhere but the intended target. I went a step further and disconnected both the virtual network adapter and physical network cable, to truly air gap my research environment. I had my malware and likely target, and it was time to test my theory that Symbiote was trying too hard to be sneaky, and would sound the alarm on itself if I poked it just right.

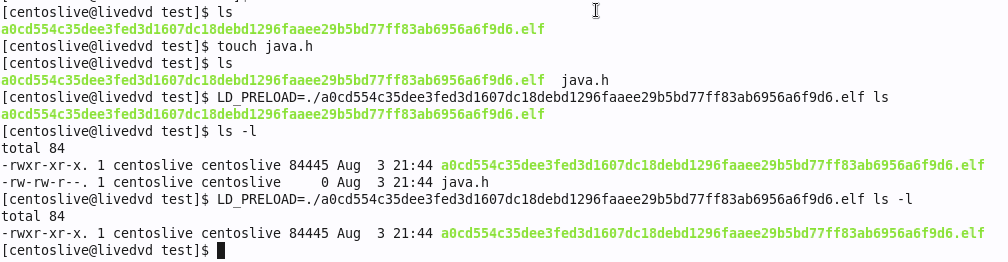

Success! We’re using touch to create a file named java.h, and using ls to verify that it’s really there. Then, add the LD_PRELOAD and run ls again, and java.h is mysteriously missing. A similar trick works for detecting process hiding. We turn java.h into a script by writing while true; do sleep 1; done into it. Run the script in the background, and see if it’s listed in ps -A -caf. For a filename on Symbiote’s hide list, it too disappears. The best part is that we can script this detection. I give you, sym-test.sh. It creates and runs a simple script for each of the known Symbiote files, then uses ls and ps to look for the scripts. A Symbiote variant that works like the samples we’ve seen in the wild will give away its presence and be detected. If you find Symbiote on your machine via this script, be sure to let us know!

BGP Hijack — Maybe

There was a bit of BGP weirdness last week, where the Russian telecom company, Rostelecom, announced routing for 17.70.96.0/19. This block of IPs is owned by Apple, and all signs point to this being an unauthorized announce. BGP, the Border Gateway Protocol, is one of the most important network protocols you may not have heard of, and essentially carries the instructions on how to route internet traffic around the world. It’s also historically not had any security protocols baked-in, simply relying on good behavior from all the players. There is RPKI, a new standard for cryptographic signatures for routing updates, but it’s not a hard requirement and not widely deployed yet.

BGP, without any of the security enhancement schemes, works by honoring the most specific route available. Apple announces routes for 17.0.0.0/9, a network of over 8,000,000 IPs. Rostelecom started announcing 17.70.96.0/19, a much smaller subnet containing just over 8,000 IPs. The more specific route wins, and Rostelecom has a valid ASN, so the Internet made the routing shift. Someone at Apple was paying attention, and pushed a routing update for 17.70.96.0/21, moving what is presumably the most important 2,046 IPs back to their proper destination. After about 12 hours, Rostelecom dropped the bogus routes. Neither Apple nor Rostelecom have released statements about the incident.

Were this the first incident involving Rostelecom, it would be natural to conclude this was an honest mistake. Rostelecom has demonstrated bad behavior in the past, so the element of plausible deniability is waning. Could this have been part of a targeted operation against someone’s iPhone or Apple account? It’s hard to say whether we’ll be privy to the details any time soon. At the very least, you can watch a replay of the network carnage.

Email Routing Hijack

Cloudflare is expanding into email routing, and researcher [Albert Pedersen] was a bit miffed not to get invited into the closed Beta. (The Beta is open now, if you need virtual email addresses for your domains.) Turns out, you can use something like the Burp Suite to “opt in” to the beta on the sly — just intercept the Cloudflare API response on loading the dashboard, and set "beta": true. The backend doesn’t check after the initial dashboard load. While access to a temporarily closed beta isn’t a huge security issue, it suggests that there might be some similar bugs to find. Spoilers: there were.

When setting up a domain on your Cloudflare account, you first add the domain, and then go through the steps to verify ownership. Until that is completed, it is an unverified domain, a limbo state where you shouldn’t be able to do anything other than complete verification or drop the domain. Even if a domain is fully active in an account, you can attempt to add it to a different account, and it will show up as one of these pending domains. Our intrepid hacker had to check, was there a similar missing check here? What happens if you add email routing to an unverified domain? Turns out, at the time, it worked without complaint. A domain had to already be using Cloudflare for email, but this trick allowed intercepting all emails going to such a domain. [Albert] informed Cloudflare via HackerOne, and scored a handy $6,000 for the find. Nice!

Post-Quantum, But Still Busted

The National Institute of Standards and Technology, NIST, is running an ongoing competition to select the next generation of cryptography algorithms, with the goal of a set of standards that are immune to quantum computers. There was recently a rather stark reminder that in addition to resistance to quantum algorithms, a cryptographic scheme needs to be secure against classical attacks as well.

SIKE was one of the algorithms making its way through the selection process, and a paper was just recently published that demonstrated a technique to crack the algorithm in about an hour. The technique used has been known for a while, but is extremely high-level mathematics, which is why it took so long for the exact attack to be demonstrated. While cryptographers are mathematicians, they don’t generally work in the realm of bleeding-edge math, so these unanticipated interactions do show up from time to time. If nothing else, it’s great that the flaw was discovered now, and not after ratification and widespread use of the new technique.

Bits and Bruggling Bytes

A portmanteau of Browser and Smuggling, Bruggling is a new data exfiltration technique that is just silly enough to work. Some corporate networks try very hard to limit the ways users and malicious applications can get data off the network and out to a bad actor over the Internet. This is something of a hopeless quest, and Bruggling is yet another example. So what is it? Bruggling is stuffing data into the names and contents of bookmarks, and letting the browser sync those bookmarks. As this looks like normal traffic, albeit potentially a *lot* of traffic, it generally won’t trigger any IDS systems the way odd DNS requests might. So far Bruggling is just an academic idea, and hasn’t been observed in the wild, but just may be coming to malware near you.

LibreOffice just patched a handful of issues, and two of them are particularly noteworthy. First is CVE-2022-26305, a flaw in how macros are signed and verified. The signature of the macro itself wasn’t properly checked, and by cloning the serial number and issuer string of a trusted macro, a malicious one could bypass the normal filter. And CVE-2022-26306 is a cryptographic weakness in how LibreOffice stores passwords. The Initialization Vector used for encryption was a static value rather than randomly created for each install. This sort of flaw usually allows a pre-computation attack, where a lookup table can be compiled that enables quickly cracking an arbitrary encrypted data set. In up-to-date versions of LibreOffice, if using this feature, the user will be prompted for a new password to re-encrypt their configuration more securely.

Samba has also fixed a handful of problems, one of which sounds like a great plot point for a Hollywood hacking movie. First is CVE-2022-32744, a logic flaw where any valid password is accepted for a password change request, rather than only accepting the valid password for the account being changed. And CVE-2022-32742 is the fun one, where an SMB1 connection can trigger a buffer underflow. Essentially a client tells the server it wants to print 10 megabytes, and sends along the 15 bytes to print (numbers are fabricated for making the point). The server copies the data from the way-too-small buffer, and uses the size value set by the attacker, a la Heartbleed. I want to see the caper movie where data is stolen by using this sort of bug to print it out to the long-forgotten line-feed printer.

And finally, Atlassian Confluence installs are under active attack, as a result of a handful of exploits. There were hard-coded credentials left behind in the on-premise Confluence solution, and those credentials were released online. A pair of critical vulnerabilities in Servlet Filters are exploitable without valid credentials. If you’re still running unpatched, unmitigated Confluence installs, it may be time to jump straight to containment and cleanup. Ouch!