[John Blankenbaker] did not invent the personal computer. Museums, computer historians, and authors have other realities in mind when they say [John]’s invention, the KENBAK-1, was the first electronic, commercially available computer that was not a kit, and available to the general population.

In a way, it’s almost to the KENBAK’s detriment that it is labelled the first personal computer. It was, after all, a computer from before the age of the microprocessor. It is possibly the simplest machine ever sold and an architecturally unique machine that has more in common with the ENIAC than any other machine built in the last thirty years..

The story of the creation of this ancient computer has never been told until now. [John], a surprisingly spry octogenarian, told the story of his career and the development of the first personal computer at the Vintage Computer Festival East last month. This is his story of not inventing the personal computer.

A Career of Small Computer Systems

A Career of Small Computer Systems

[John] began his career as an intern working at the National Bureau of Standards in Washington, D.C. He was assigned to the SEAC, a project to build a relatively small computer for the US Government before a much larger computer could be completed.

The SEAC was a small computer, but it was not by any means simple. There were over seven hundred vacuum tubes in the racks, tens of thousands of very expensive diodes for all of the logic. The memory was a set of mercury delay lines — tubes, filled with liquid mercury, with acoustic transducers at each end. These transducers would send pings through the mercury, representing zeros or ones. Because of the speed of sound through this mercury, a small amount of information could be stored, like a gigantic shift register.

There were only a handful of instructions available for this computer – addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, comparison, and an instruction for input and output. There weren’t many instructions, but it was enough; SEAC was the first stored program computer in the United States, and the only computer in Washington, D.C. Everything from calculations needed by Los Alamos to navigation tables for the new LORAN network were created on SEAC.

After working for the National Bureau of Standards, [John] moved on to Hughes Aircraft. His work on the SEAC made him extremely valuable for another small computer – an airborne computer, built in 1952. This was only a few years after the development and commercialization of the transistor, and as such this airborne computer used the latest vacuum tubes, arguably the most technologically advanced vacuum tubes ever made. All the memory was contained in a rotating magnetic drum, and most of the logic was implemented with diodes so expensive they were stored in a safe.

This was the very beginning of the computer age, and as such semiconductors were in short supply. Adding a flip-flop to a design meant the cost of this computer would increase by $500. It was the time of small computer systems, and the architectural limitations of early computers wasn’t because they couldn’t build them bigger; these computers were small because anything bigger would cost too much.

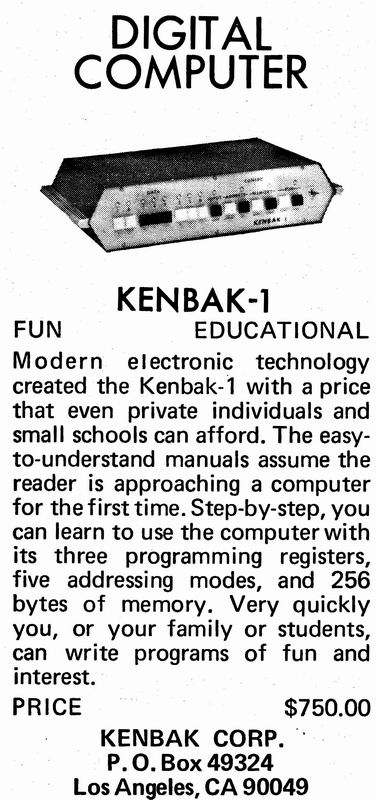

Building the KENBAK

In 1970, [John] found himself unemployed, with $6000 in his bank account from a severance package. He decided if he was ever going to build a small computer, this was the time. He wanted an educational computer — a machine that would teach people how to use a computer. It would have to be cheap, and something that a single person could operate. A personal computer, if you will.

[John] settled on a very basic computer, with an architecture not unlike the SEAC he built 20 years before. There would be three registers, A, B, and X. Five addressing modes complimented a handful of instructions – add, subtract, load, store, AND, OR, a few jumps, conditionals, I/O, and of course a NOP. The memory would be two shift registers configured as serial memory, a much smaller and less toxic version of SEAC’s mercury delay line memory.

With the right architecture in hand, [John] began building his computer. To keep costs low, he went with off-the-shelf parts. The were 132 standard TTL logic ICs, accompanied by two 1024-bit MOS shift registers. The machine had 256 bytes of memory (although the word size was not eight bits), and no ROM. It wasn’t fast, it wasn’t powerful, but anyone could program it by punching ones and zeros into the front panel.

With a design and a few tweaks to the circuit, [John] had a computer. The plan always was to manufacture this computer. That meant sales, and that meant a market.

It’s easy to see the ideal market for the earliest computers would be scientists, academics, and engineers when looking back on nearly fifty years of computer history. Universities were Digital Equipment Corporation’s largest market after the government, after all. [John] designed the KENBAK as a computer trainer, and decided teachers — high school and community college teachers — would be the market where the utility of a personal computer would be apparent.

In May of 1971, [John] trundled out his booth to a convention of high school mathematics teachers nearby. The computer worked, and he had a few programs loaded into the memory, the most memorable of which would give the day of the week for any date in the 1900s. There are eight lights across the face of the KENBAK, and with just a little bit of code, this computer would blink the first light for Monday, the second light for Tuesday, all the way down the line until an invalid date would light up the eighth light.

Apparently, and to [John]’s great surprise, high school mathematics teachers don’t know the rules for the calendar. Nevertheless, he did get a lot of interest from private individuals, colleges, and universities. KENBAKs were shipped around the country, to France, Italy, Mexico, and Canada. Only forty or so KENBAKs were ever sold, with seven units ending up at a technical college in Nova Scotia. Canada.

Recognized As The First Personal Computer

In the mid-1980s, long after selling his inventory off and moving across the country to Pennsylvania, The Computer Museum in Boston — the forerunner of the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California — announced they were trying to find the first personal computer. These submissions (or more cynically; these donations to the museum) would be judged by a panel of technologists including [Woz], [David Bunnell], the publisher of PC World, and [Oliver Strimpel].

Of course, any attempt to find the first personal computer eventually becomes an argument of adjectives. Computers had existed before 1970, going back to [Konrad Zuse]’s Z3, the Colossus at Bletchley Park, or later the programmable ENIAC. These computers were each firsts in their own way, and technically the Computer Museum produced two winners for their ‘first computer’ contest; the French Micral from 1973 was called, “the first commercially available microprocessor based computer.”

The KENBAK, according to the Boston Computer Museum, The Computer History Museum, and [Woz] himself, was the first electronic, commercially available computer that was not a kit and available to the general population.

The KENBAK, according to the Boston Computer Museum, The Computer History Museum, and [Woz] himself, was the first electronic, commercially available computer that was not a kit and available to the general population.

Of course, [John] will never say he invented the personal computer. He says there were people who had built computers out of logic chips before him. Those people just didn’t commercialize their computers. There were computers sold to the public before the KENBAK, as well. [John] remembers a computer sold by FAO Schwartz that had a drum with pins and holes, and would complete operations in an automated fashion.

“One of the things that people sometimes say about this is that I invented it. I always say there was no invention, it’s just logic, only ones and twos, that’s all it is,” [John] said closing his talk at the Vintage Computer Festival, “there was no radical thing that I invented. I just programmed a computer.”

Cool story

“It is possibly the simplest machine ever sold”

My hammer would beg to differ.

Yes, but your hammer isn’t programmable…

Converts 1’s to 0’s

+1

*swings hammer*

+0

But most hammers are user programmable. think about the many ways people use or misuse hammers ;)

I see your hammer and raise my wooden stick.

As far as simplest ‘computer’ sold to the general public, you can’t find them less complex than the GENIAC series of state machines designed and marketed by Edmund C. Berkeley from 1955 through the Sixties. The consisted of six N-pole by N-throw rotary switches, which could be jumpered up and cascaded to perform logical functions.

A refreshingly modest individual. Something sadly lacking in the industry…

+1 a rarely appreciated quality

And here it is again, some 6 years before, but not completely electronic as it had a mechanical printer and keyboard: the Olivetti Programma 101. That one even had a magnetic card memory to save the programs.

God Bless you, John. Your work and device stimulated others to make larger, faster and more programable

machines. Your work may have created interest in the budding 4004 and 8008 chips.

I drooled over the SCELBI machine ads and schemed as best I could to find money for one. Good thing i

waited, since the 8080 and later Z80 chips hit the world in full force and Apple and Radio Shack got into

the business. I don’t want to shortchange the 6502 family, since they also made a huge impact on the

world market of computers of various sizes, shapes and capabilities.

I say give John the credit for some ‘FIRST’ that will endure the decades of various ‘nigglers’ who spend

their time arguing about phrases about various topics as opposed to real issues. Words may be man’s

greatest tools, but as long as the ‘nigglers’ abound, we will constantly be sidetracked by analysis of nouns,

verbs, adverbs and probably the diagramming of sentences!

The Scelbi is important too, since it came right before the deluge. I don’t think I noticed the ad in QST, it was in the back of the magazine. What I remember is a post-Altair reference, and I went back and found the ad as a result. The ad was there, but not a mention at the time in the hobby electronic or ham radio magazines I read at the time.

Michael

Multiplication and division on the SEAC? (Also mentioned on the Wikipedia page for SEAC.) Curious how these were implemented…

Probably using a shift + add/subtract algorithm. It is relatively easy and requires few extra resources.

“there was no radical thing that I invented. I just programmed a computer.” Oh you invented something alright.

This reminds me of Neil Peart of RUSH saying that he “just hits things with sticks.”

I don’t really care for Rush, but Neil is an absolutely amazing drummer!

The Kenbak-1 has a pretty easy and surprisingly sophisticated instruction set, significantly more so than a pdp-8 and the first generation of micro processors.

http://www.kenbak-1.net/index_files/page0009.htm

The quoted speed of the CPU can’t be 1MHz, since AFAIK the CPU is completely serial: the core can only execute instructions at 62.5KIPs max, since most are 16-bits (and the serial ram reduces this to under 1Kip in practice).

There is a bit of a fallacy about old computer designs being the simplest possible, but this is not really the case. Colossus (which wasn’t really a computer) required 1600 to 2400 valves, but the later Manchester Baby, the first von Neumann computer only had 550.

The pdp-8, the first-ish minicomputer had the equivalent of about 6400 transistors (10K diodes + 1.6K transistors), approx 3200 gates making it as it nearly twice as complex as a 6502; which was about 50% more complex than the first MPUs.

Nor is the kenbak-1 the simplest viable 8-bit TTL computer, the Mark 1 forth computer has about half the number of TTL chips.

The question then is why, when the resources were so limited they didn’t implement the simplest machines. My best guess is really a combination of three things:

1. The earliest or pioneering computer designers only had one shot at their designs, therefore they had a tendency to play it safe. the exception in this list is probably the Manchester Baby, which evolved from a machine to test williams-kilburn CRT memories.The baby involved a lot of experimentation.

2. Even most early computers were based on earlier designs. The pdp-8 was based on the pdp-5. The legacy designs influenced the complexity.

3. The implementation technology influences the architecture. TTL is a quite crude building block, because you always get several types of gates in 1 package, so there is a tendency to adapt the design to the available gates. This was also true for the pdp-8 since it was built up from hundreds of standard DEC ‘flip-chip’ mini-PCBs.

Still great article!

I don’t get why you think the CPU would be serial??

74xx gate chips most often 2 inputs so they make good CPU building blocks.

As for design history. Well there were many stages and there were different influences at different times. Sure at one time the target was *simple* but when you’re talking about so much history then the target was different at different times / technologies.

The 74xx building block *does* have several types of gates and so there wasn’t so much of an effort to design things to suite the gates. It was more about managing the permutation space of the instruction set to minimize the gate count and sequential gate delay. The instructions themselves had cycle limits and propagation delay limits more than anything else.

I tried to find a schematic for this but no go. I am guessing from the era that it was built on the most basic SSI like x input [x] gate and not more MSI like parts such as shift registers and adders.

The November 1972 issue of “73” bad an article bout building your own computer. It wasn’t a construction article, but mapped out what would be needed, right on the cusp of the arrival of microprocessors. So core memory is suggested, from the surplus market, and ttl was the obvious choice. I haven’t looked at it recently, but I suspect it was influenced by a minicomputer or two.

We forget, but a few people did build computers (or resurrect commercial computers) before the microprocessor arrived. People who badly wanted them, lots of work and space, and then often obsoleted by something much smaller and capable. If nothing else, a microprocessor meant other people doing the same thing.

But that period is sort of lost, not quite visible at the time (because it was niche then, so not much space for it in general hobby electronic magazines) and ten dwarfed by the microprocessor computers. Once there were home computer magazines, the focus wasn’t on building at the ttl level, even if there was suddenly magazines and space to write about them.

Mcgael

“I don’t get why you think the CPU would be serial??”

Because the Kenbak manual says it is (see page 16), and says it has a serial adder/subtracter (page 21), and it provides the circuit to the computer which describes a serial architecture. And it makes sense, the Kenbak-1 has serial memory, so serial computation is easier that way (and slightly faster as you don’t have to wait for an entire byte to be loaded into registers before starting the ALU).

Here’s the manual:

http://kenbak-1.net/index_files/Theory%20of%20K-1.pdf

It’s all typed out in courier :-) Happy perusing!

I like the reassurance “you should expect months or even years between significant failures”! Wow, that’s reliable, compared to maybe an ENIAC!

Was the memory entirely serial? I have half an idea the shift registers were arranged with some parallelism, pumping out several bits at a time.

The document doesn’t appear to be a “true” PDF. Seems like just bitmap scans of the pages, no OCR, so the characters are just bitmaps, not characters. So you can’t search it, for one thing. Bit of a shame, I’m sure there’s tools available that will recognise the characters and generate a “true” PDF, which will also be a smaller file (admittedly not a huge problem for 2MB but still, back in the day…).

I heard about the Kenbak a few years ago (through the Internet so a bit too late to own one), VERY interesting, and great that he managed to build it using what was available, even for a decent price. At the time, I suppose, an amazingly cheap price considering the competition, even though it’s only really a little demo computer. Probably not reliable enough for industrial control, and not powerful enough for processing real information. Still, add a bit more SAM (aka serial non-random access memory) and you might’ve been able to get somewhere with a teletype and maybe 4K of ROM for BASIC or FORTH.

I bet, too, that with just a few more components, you could do all sorts of interesting things with it, I bet a lot of users added extra stuff to it. Wonder if you could get it to play Tetris on a grid of LEDs? Or at least Pong. I might allow using an LCD with drivers, if it helps.

I found the same pdf elsewhere but it is the same – scanned pages.

The memory is two streams of 1024 bit serial Sequential Access Memory (SAM) so a total of 256 bytes.

There are several clones around. Here is one example –

http://www.funnypolynomial.com/software/arduino/kenbak.html

There’s a very very cool Kenbak replica based on – of course – an Arduino:

http://www.funnypolynomial.com/software/arduino/kenbak.html

A quick Google search reveals they were quite pretty on the inside.

Despite his humility while Jon didn’t invev tanything he did create a product. However with only around 40-50 units sold, I doubt the KENBAK really had that much influence on very many that went on to create successful personal computers. A photo in this article reveals what physical beast the machine ishttp://www.bbc.com/news/business-34639183 , a lot of 7″ tablets would fit inside that cabinet.

It’s strange to see in the picture a fan inside of the Kenbab’s case, but no holes in the case.

It looks like there was a component that ran hot (maybe a voltage regulator) and spreading the heat around the inside of the case cooled it sufficiently without pulling dust into the computer.

Looks like I’m wrong. This page explains the airflow: http://www.kenbak-1.net/index_files/page0003.htm

There’s that slot in the front, what’s that for?

There is a kit avalable if you want tout build your own replicate.

http://www.kenbakkit.com/

Back in the day we actually had two of these at my school in the San Fernando Valley. Who knew there were only 40 in existence?! They were used to teach basic logic operations but since nobody had the slightest grasp of computers it was not the best teaching tool. You had to learn one unfamiliar concept using another unfamiliar concept. They were kind of magical to me, but generally ignored. One kid I remember got a lot of use from it by entering and playing back code so that the instructions lit the dots in patterns, like chase lights. I don’t remember anybody ever saying “this is the future.” We were idiots. So cool that there are emulators and replicas now.

User40, you actually saw a Kenbak-1 back in the 1970’s? I’d love to hear details.

So this guy does not invent the PC and he gets an article yet I never invented the PC better than he ever did and I get jack!

My problem is, I keep inventing things, or ways of doing stuff, only to discover someone else has already done it. I feel like such a genius… for a day or so.

I was remotely focusing a B&W rooftop camera years ago, and noticed that as the image came into focus the whites were brighter and the darks were darker. I thought that by analyzing the peak to peak video signal, an auto focus could be made. Later, I found out Sony had patented it years before…

Heh, the contrast trick? I wondered how passive focus cameras worked for a long time. Was one of those things I refused to Wiki till I could figure it out. Very clever setup.

But finding that someone else has done it before doesn’t diminish that you figured it out yourself.

I’ve done it lots of times and it’s a reinforcement to find that someone has gone there before. It’s better than the norm where people say something based on something they heard, without realizing they didn’t think it up themselves.

You can have the reverse, see something and dismiss it, “no, thus can’t be useful”, then later see something like that, but in this case the date is a good indication that you thought of it either first, or at the same time. This doesn’t even have to be a major insight, sometimes looking at something and seeing something subtle is important.

Michael

First commercial computer in a private house was a PDP-8/S in 1967, watch https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8KkW8Ul7Q1I from about 10:30 to 16:40. There was an earlier LINC in a home in 1965 but that was a research computer.

Great work Brian! Very enjoyable read.

I installed a MONROBOT XI computer in a private house in 1967. It was the home of Warren S. Woolley in Morristown, New Jersey. The MONROBOT XI computer was designed and built by Monroe Calculator Co. of Orange, NJ in 1959. In 1967 a new company, Computer Property Corp. was formed to take over the complete line from Monroe. The company was established in West Hanover, NJ and New York City. There were 350 MONROBOT XI computers installed and running at the time of the take over. The software company, Systems Design, Inc., was already established by Peter George Petropolis of Randolph, NJ and had the majority of the MONROBOT XI installations, which were Banking back offices, Fuel Oil delivery companys, various payroll, accounts payable, accounts receivable, general ledger, etc. Monroe had done some initial software for various installations too. Warren S. Woolley was processing payroll and other accounting work for restaurants known as diners, known as “tips payroll” because it could handle tips received by workers as the restaurants. The programs were written in machine language and there was an assembler, which I modified and improved. Many existing installations would send Systems Design, Inc. a program punched into 8 channel paper tape, along with printed results that were both current and with handwritten requests for changes and additions. I wrote a dis-assembler that built an assembler source 8 channel paper tape, which could then be printed, modified, etc. to satisfy the requests that required new programming. There was also a magnetic card with 96 32 bit registers, known as the MonroCard. Cards were used for employee payroll, fuel oil customers, anytime data storage in that form was more practical than 8 channel paper tape. The MONROBOT XI computer had a drum with 2,048 32 bit words, five fast access registers, and vacuum tube I/O. Printing was done using the IBM Model B typewriter, the keyboard was also the input device. Later, the IBM selectric type writer was interfaced. IBM 026 keypunch machines could also be I/O. The entire operation of all MONROBOT XI computers came to an end in 1974. If anyone has one of these computers then consider a donation to VCF Federation museum located at Infoage.org which has a bricks and mortar museum at Camp Evans in Wall, New Jersey.

I programmed a Monrobot XI at Randolph, NJ High School in the early 1970’s. It had been donated to the school. Given the other connections to northern NJ, I wonder if it was donated by one if the individulas or companies mentioned.

It’s an ill misconception from computer museums that the Kenback-1 was the first personal computer. It wasn’t really even close. The honor would likely go to either the Mathatronics Mathatron or the Olivetti Programma 101 that were both introduced over a half decade before the Kenback-1. Even the Wang LOCI-2 coined the term “Personal Computing” on the cover of its owner’s manual in 1964.

The Computer Museum in Boston was the descendant of the DEC Computer Museum, which was conceived and founded by Gordon Bell, DEC’s VP of Engineering. The museum started in Maynard, moved to Marlboro and, when it grew too big for DEC, moved to Boston, next tot he Children’s Museum on Fort Point.

When in Marlboro, I visited it, and it was the first time I saw a German Enigma machine.