If anything about electronics approaches the level of black magic, it’s antenna theory. Entire books dedicated to the subject often merely scratch the surface, and unless you’re a pro with all the expensive test gear needed to visualize what’s happening, the chances are pretty good that your antenna game is more practical than theoretical. Not that there’s anything wrong with that — hams and other RF enthusiasts have been getting by with antennas that work without really understanding why for generations.

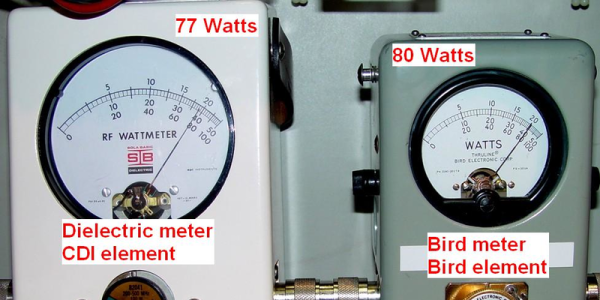

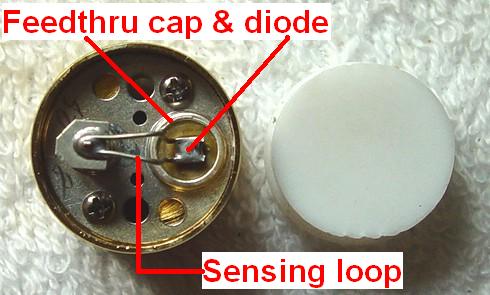

But we’re living in the future, and the tools to properly analyze antenna designs are actually now within the means of almost everyone. [Andreas Spiess] recently reviewed one such instrument, the N1201SA vector impedance analyzer, available from the usual overseas sources for less than $150. [Andreas]’s review does not seem to be sponsored, so it seems like we’re getting his unvarnished opinion; spoiler alert, he loves it. And with good reason; while not a full vector network analyzer (VNA) that will blow a multi-thousand dollar hole in your wallet, this instrument looks like an incredible addition to your test suite. The tested unit works from 137 MHz to 2.4 GHz, so it covers the VHF and UHF ham bands as well as LoRa, WiFi, cell, ISM, and more. But of course, [Andreas] doesn’t just review the unit, he also gives us a healthy dose of theory in his approachable style.

[The guy with the Swiss accent] has been doing a lot of great work these days, covering everything from how not to forget your chores to reverse engineering an IoT Geiger counter. Check out his channel — almost everything he does is worth a watch.

Continue reading “Putting A Poor Man’s Vector Analyzer Through Its Paces”

![[Source: Wikipedia]](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/350px-standing_wave_2.gif)