Even in this age of wearable technology, the actual fabric in our t-shirts and clothes may still be the most high-tech product we wear. From the genetically engineered cotton seed, though an autonomous machine world, this product is manufactured in one of the world’s largest automation bubbles. Self-driving cotton pickers harvest and preprocess the cotton. More machines blend the raw material, comb it, twist and spin it into yarn, and finally, a weaving machine outputs sheets of spotless cotton jersey. The degree of automation could not be higher. Except for the laboratories, where seeds, cotton fibers, and yarns are tested to meet tight specifications, woven fabrics originate from a mostly human-free zone that is governed by technology and economics.

The Automation Gap

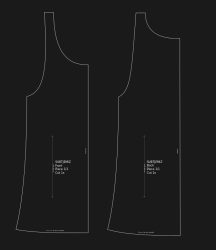

After the fabric is woven, however, the automation ends abruptly — clothes are still a mostly handmade product. Precisely where all the pieces finally come together, a big automation gap has grown. To make a batch of a piece of garment, a shirt for example, hundreds of layers of fabric are stacked with a printed paper template of the cutting pattern on top. A technician then uses a special tool (the electric straight-knife cutting machine) to trace the contours of the template, simultaneously cutting hundreds of parts. A fleet of sewing machines run by diligent sewers then buzzes those pieces together to make shirts, tees or pants. Assembling garment is a laborious process, and RMG-factories (Ready-Made-Garment) are naturally found where labor is cheap.

If you look at how garments are composed, that makes sense: can you imagine another way how to reliably align all the soft fabric pieces and put a seam in place? Garments are designed for manual sewing. Since the Industrial Revolution, fabrics have become lighter, sewing techniques have progressed, and wherever the grown manufacturing chain allows it, short stages of automation have been spliced in. Functional fabrics, ultrasonic sewing techniques, CNC template cutting, automated stitching and various printing techniques have been added, but the overall process itself remains unchanged.

Filling the gap

Unfortunately, no other material is as cheap, abundant and comfortable as the soft and flexible cotton jersey from the automation bubble, because it’s not by itself amenable to further automation. It can’t be practically glued or welded, it’s kind of a stubborn material to feed into an automated process, and it makes redesigning garments for automated manufacturing a huge challenge. However, this redesign process is happening now, and it’s following patterns that we have seen before in other areas of manufacturing. From the development of desktop machines that virtually print garment on the fly to entirely new manufacturing methods that leave the paved way of cheap, subsided cotton, everything seems possible.

OpenKnit

Computerized flat knitting machines use a large array of hundreds of mechanically or electronically latched knitting needles to turn yarn into arbitrary, wearable shapes. Gerard Rubio started OpenKnit in 2014 as an open source project to develop such a machine, and the project matured greatly since then. Gerard recently founded Kniterate and announced a Kickstarter campaign to fund a desktop machine that prints ready-to-use garment. The knitting technique works best with thick yarns, typically for pullovers, caps and winter socks. Knitting is still unsuitable for producing light fabrics, but if you want to print your own pullover right now, there’s actually no need to wait.

Fabrican

If you like it tight, you at least have the mold already. Fabrican uses your body as mold for a perfectly fitting, seamless piece of garment. Fashion design student Manel Torres invented Fabrican in 1995 by adapting the resin-like composition of Silly String, geared up an R&D facility and perfected his idea. Fabrican is basically a spray can that contains a polymer solution with a highly volatile solvent. After being applied, the solvent dissolves quickly, leaving a soft layer of non-woven fabric polymer behind.

Although the formulation appears to have reached a point where very fine and light, washable garments are possible, Fabrican isn’t exactly a commercial success. The most likely reason for this may be that people don’t want to spray chemicals on their bodies to make their own garments, although most video demonstrations also suggest that the spray-on fabric is not very flexible, rips easily and is therefore not too practical. Possibly, the technique could be improved by using fibrous filling materials in conjunction with flexible polymers. Given a non-human mold and more practical materials, the method makes a great starting point for fully automated garment production.

Electroloom

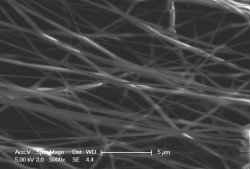

Electroloom uses an electrospinning process that applies non-woven fabric to flat or three-dimensional, metal molds for automated production of seamless garments. Unfortunately, a Kickstarter campaign and a research grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) was not enough to finance through the development of an electrospinning process that can be used for garment production. The founders recently announced the end of Electroloom. Nevertheless, the technology that has been demonstrated by Electroloom over the last year has been promising.

The process requires a high voltage potential to be applied between a conductive emitter nozzle and a metal mold, such as the metal tank top shown above. A polymer solution is then slowly dispensed from the nozzle, where electrostatic repulsion forces fine fibers to emanate from the liquid before being accelerated towards the surface of the mold. The fibers stretch, thin down to a few hundred nanometers, and dry during their flight towards the mold, where they build up to a fine, fabric-like material. The mold is moved or rotated during the process to ensure an even material build up. Once enough material has been laid down, the process is stopped and a piece of garment can be peeled off the mold.

Electrospinning was originally invented as a textile manufacturing process, but never found wide adoption. Currently, common applications of electrospinning are filtration materials, wound dressing materials, tissue engineering and other use cases that require small amounts of very fine, absorbent tissue. Even though Electroloom’s announced garment printer will never be released, their vision of a fully automated production process for practical, light garments remains.

Automate, Now!

We’re in the midst of the “Automation” phase of the 2016 Hackaday Prize, a competition to drive social change through creating. Garment manufacturing is one of the industries that provide both an immense demand for automation as well as the opportunity to disrupt some of the quirky, grown processes chains. If you have an idea on how to manufacture garments better than it’s currently done, hop over to hackaday.io, get feedback from the community and make it happen while winning some awesome prizes! Any other ideas? Let us know in the comments below!

Thanks to [regan67] for the photo of the sewing machine in the title graphic!

Nice one Mr Rubio, those knitting machines were ripe for full automation, I remember seeing punch card operated ones in the 80s. My family had a manual one, still faster than hand knit. However, have fam into crafts now and know that it seems now you can buy 3 sweaters for the price of the yarn to make one, whereas back in the day it was more like yarn for 3 sweaters for price of one sweater…… there must be huge bulk discount thing happening there.

Also commercial markups. A retailer will typically mark up a sweater (say 19.99) by 100%, which means they buy from the wholesaler at around 9.99/ea. The wholesaler will buy from a larger distributor that handles imports, or the manufacturer (rare). The price from the distributor or the manufacturer in this case would be roughly 5.00/ea. Then, that doesn’t even take into account the price breaks per unit that each level may see.

In order for garment manufacture in the 1st world to match the prices of those made in the 3rd two things need to happen. 1) complete sewing automation (this handles nearly all plain clothing: t-shirts, jeans, and variations of these), and 2) automated bulk material handling.

The parent company of Wrangler and Lee (jeans) developed a zipper-sewing machine over a decade ago. It was semi-automatic (humans had to position the jeans and the zipper in the machine, then hit the button) but it did automate the most labor-intensive and defect-prone step.

Seamless knits are mostly a solved problem now (they’re kind of just socks on steroids) but wovens have plenty of room for development. Big problem is making a seamless woven that drapes well. Also, the cost – this is a market where China is getting too expensive to be competitive anymore.

So two of the three “advancements” involve making plastic fabrics. No thanks, I don’t think of that as an advancement.

I’d look into new ways to apply the cotton fibre without first turning it into yarn. Flock printing?

You should also check out SoftWear. I just learned about them from the Planet Money Podcast. http://softwearautomation.com/

I can’t wait to see where this could go as I would love a machine that could make clothing to my exact measurements whenever I want.

You should include SoftWare in this list as well. I just learned about them from the Money Planet Podcast

The EU funded a bunch of research in this area in the early-mid 2000s (Google Project Leapfrog). Like most EU research projects this didn’t seem to yield much real progress, but it’s the best-funded effort in this area I’m aware of.

http://www.leapfrog-eu.org/LeapfrogIP/main.asp?pg=rmb_results_contents

The other piece of the “short automation” chain is that there are a multitude of sizes, patterns and colors being produced. It might be possible to set up an automated device to crank out a half-dozen sizes for a year straight, but for a single style of blue jeans alone you’re looking at perhaps thirty different waist sizes and probably a dozen inseams all done in batches of a few hundred or a few thousand. These types may change between retailers (for instance, having WalMart’s batch be separate for cost savings). When you add pattern-matching, fastener differences etc for prints/weaves and the rest of it, human sweat-shops are the usual end result.

Also, as a Hirsute-American; “Fabrican” or any other sprayed, rolled, printed, adhered, or otherwise deposited “clothing” is the stuff of follicle-pulling nightmares.

If you can solve most or all of the individual steps with something CNC-like (not in being a n-axis bot but in that a single machine can make items of variable size within a given range of sizes) for each step, then it shouldn’t be a huge leap to then chain them all together.

I think a more interesting advancement would be to make clothing designs parametric, instead of having to manually adjust a given design for every single size combination. Then anyone could get anything in any size, even custom fit …

The article started out with bold ideas and then quickly deteriorated. Too bad.

Disney also has a really interesting project with 3D knitting and automation:

https://www.disneyresearch.com/publication/machine-knitting-compiler/

they’re able to make very neat volumetric shapes by cleverly manipulating the knitting machines

Lots of companies already automate cutting out of patterns, exmoor trim posted this vid in 2012, I’ve recently bought a landrover hood from them that was cut out with this process, they can now keep all their designs on computer, and they do interior trim, seats etc too by the same processes.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ojj2GURhPwE

Yeah, there are a TON of options for automated material spreading and cutting that this article completely glosses over (look up Lectra, Gerber, and Eastman for starters). That is largely a solved problem and is practically required for cutting advanced textiles.

Automated sewing however, is still very much in it’s infancy even though there are numerous examples and multiple companies specialized in making automated sewing equipment (look up Schroeder Sewing Technologies). It’s highly specialized though, very tricky stuff that is completely dependent on the specifics of the application. Automated handling of cut fabric is very complicated.

Not to mention that sewing goes WAY beyond garments…

https://vimeo.com/121363304

The problem is that hand guided sewing requires sensing of the fabric and the level of sensor in the fingertips and the processing that interprets the results, combined with the visual sensors and backing processing is still far beyond current abilities to program, even where computational facilities are available to process it. Most automations require significant simplifications that are not available in the degrees of freedom a bit of cloth has.

Just watch the video of a robot folding a towel. https://youtu.be/5FGVgMsiv1s?t=28

I want a knitting robot that only uses a couple needles and some extra hands. Hopefully it looks like a spider.

Automating the garment fabrication process will destroy the livelihoods of thousands or tens of thousands of women in developing countries. Your clothes may be cheaper and it may increase the profits of the corporations, but automation will throw many into destitute poverty.

As long as the garment factories are well run and do not abuse the employees, I have no problem with them. Not all automation is a good thing.

work only for the sake of work isnt a good thing,i dont know where this illusion that everyone has to spend at least half their time working or they arent productive to begin with comes from.

if you look at this with a bit of context then it amazes me that anyone is still working more than 40 hours a week, unless of course that is what they specifically want, not because of work or finance but want.

the average human today is hundreds of times more productive than a human a hundred or two years ago, how come we dont take that into account?

@Tim Carlson

We’re going to reach a point where we as a society need to accept that the value of a person doesn’t flow from the work they do, and the ability to feed one’s family needn’t either.

In other words, if there literally isn’t enough work to be done, why make people work? A lot of folks will be opposed to accepting that point for all sorts of reasons, but I don’t see another way forward, absent some “corrective” and possibly cataclysmic change in the supply of human resources.

People need to work to support themselves and feed their families. This is even more important in developing countries. These are countries with little to no resources to help support and feed people who are starving and out of work. Those people and their families will starve if you take away those jobs without providing some sort of replacement.

I don’t mean make something up for them to do and pay them for it. And I honestly don’t have a good solution in mind. I am not an expert on economics in developing countries.

I’m not against pursuing automation. It’s just my opinion that we need to consider the ramifications to removing thousands of jobs from the kind of people who’s lives might, quite literally, depend on them.

@BlueFootedBooby

The places we are talking about will most likely be among last ones that will reach the point in society that you are talking about.

the issue isnt easy but even in china automation is rising and they have a massively populous country.

i think the real issue is that despite becoming more and more productive people still have to provide the same effort for the same reward or as we see in some countries even less reward than previously, something that ultimately means that somewhere someone are enjoying the benefits of that increased production.

of course people need to live but if we had a somewhat sane and grounded economic culture then automation would only make it easier for people to live, as we have seen it time and time again through history, there is of course always short term instability as the work force rearranges and new methods are taken into use.

now the real question is whether or not our economic culture still allows that.

I suspect it will be somewhat self-regulating. As more production gets automated, the bottom of the food chain will get more and more desperate. When ten cents an hour sounds a whole lot better than zero, sewing will cost ten cents an hour. That’s cheaper than the real estate that the robot is sitting on plus the cost of the power to run it – never mind capital cost and depreciation. Now whether ten cents an hour will pay for the calories to keep the human alive, that’s another question. The cost of ~1600 calories a day and some primitive shelter from storms probably sets the lower bound for labor costs.

Point is, there’s always a bottom somewhere. I know it sounds horrible, and I hate it myself, but we’re headed there barring some massive jolt that sends a Non Maskable Interrupt to the system (like, say, WWII did, or the black plague).

I’m still not sure how I feel about this idea myself but in regard to full automation, which would displace thousands/millions of workers, does anyone support some form of basic universal income to combat its effects?

I agree with Matt above, I can see where it makes sense, but so many people would be left without a job.