Nothing brings out the worst in humanity like war. Perversely, war also seems to exert an opposite if not equal force that leads to massive outbursts of creativity, the likes of which are not generally seen during times of peace. With inhibitions relaxed and national goals to meet, or in some cases where the very survival of a people is at stake, we always seem to find new and clever ways to blow each other to smithereens.

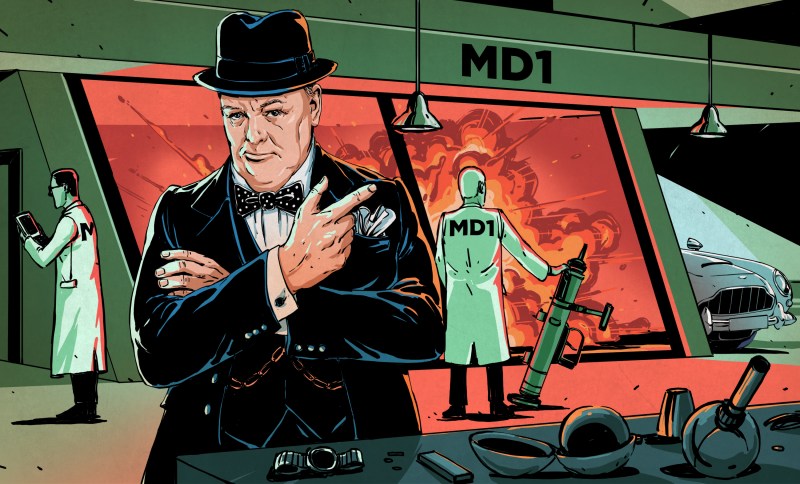

The run-up to World War II was a time where almost every nation was caught on its heels, and the rapidity of events unfolding across Europe and in Asia demanded immediate and decisive response. As young men and women mobilized and made ready for war, teams of engineers, scientists, and inventors were pressed into service to develop the weapons that would support them. For the British, these “boffins” would team up under a directorate called Ministry of Defence 1, or MD1. Informally, they’d be known as “Churchill’s Toy Shop,” and the devices they came up with were deviously clever hacks.

MD1 and the Limpet Mine

The roots of MD1 stretch back at least to 1939. As Hitler’s forces swept across Eastern Europe, newly appointed First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill could see that his country was a sitting duck. With nothing to rely on but a stockpile of outdated weapons left over from The Great War, he began a frantic effort to gear up for the inevitable. With few resources and little time, he knew that this would require ingenuity.

Tasked with research that could develop weapons for irregular warfare, the Military Intelligence Research department of the War Office was commanded by Lt. Col. Joe Holland of the Royal Engineers, a corps of sappers, or demolition experts. Holland brought along Major Millis Jefferis, also a sapper, as his second in command. Together they would assemble the team that would morph in MD1, as well as actively invent and test weapons themselves.

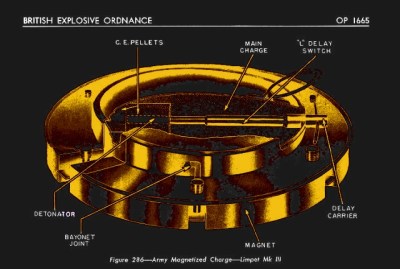

One of the earliest needs identified by MD1 was a mine that could be deployed against enemy shipping by special operations forces. Jefferis began thinking through the problems involved and decided that a powerful magnet would be used to stick an explosive charge to the hull of a ship below the waterline. The first job was to source magnets powerful enough to do the job, so he contacted Stuart Macrae, editor of a popular science magazine which had recently featured an article about magnets that seemed like they’d do the job. Macrae, a former sapper himself, already had a security clearance, which eased his integration into MD1. Originally a civilian contractor, Macrae quickly found himself back in uniform and a member of MD1 for the duration.

Macrae decided to contact an inventor acquaintance for help with the magnetic mine. Cecil Clarke, himself a sapper in World War I who never outgrew his enthusiasm for explosives, joined the team and threw himself into the work. With magnets procured, he and Macrae worked up a prototype casing for the mine using metal salad bowls from a five and dime store. They worked out a harness to allow the mine to be strapped to a very brave frogman, played with buoyancy using porridge as a substitute for the explosive, and practiced placing the mines in a local swimming pool, with a cooking griddle standing in for a ship’s hull. A spring-activated trigger was rigged with a slow dissolving ball of hard candy holding the plunger back, allowing the frogman time to get away. They dubbed the invention a limpet mine after its resemblance to the shellfish of the same name.

The limpet mine prototype was quickly engineered into a production device and farmed out for manufacture. With 4½ pounds (2 kg) of high explosive, limpets were used to sink 39,000 tons (35,800 tonnes) of shipping in Singapore harbor in 1943, and a smaller version dubbed The Clam was adapted for use against tanks on land.

The Sticky Bomb

Another nasty bit of hardware to spring from MD1 efforts was the sticky bomb, destined to be used against tanks and other armored vehicles. From his sapper days, Jefferis knew that spreading an explosive charge out over a broad area on armor plating would make it easier to rupture, so he set his team at the problem of building a powerful bomb that could be thrown against a surface, spread out evenly, and adhere firmly before detonation.

After Jefferis’ initial experiments with bicycle inner tubes filled with explosive and coated with glue proved fruitless, he turned the project over to Macrae. He realized that the grenade needed to be rigid when thrown but deform on impact, which he demonstrated with a lightbulb in a sock. These experiments eventually ended up with a glass sphere containing 1¼ pounds (½ kg) of nitroglycerine and wrapped in a fabric covering. The fabric was soaked in birdlime, a horrifically sticky substance made from boiled and fermented holly bush bark that was once used to trap nuisance birds. The sticky bomb was packaged in a shell with a handle to protect the adhesive and provide a means of tossing it.

The sticky bomb had flaws, including the tendency for its handle to fly back toward the thrower like a bullet when the bomb detonated. But it was still successful; produced in large numbers, it saw service in many of the theatres of the war, and was even provided to the French Resistance for guerrilla activities.

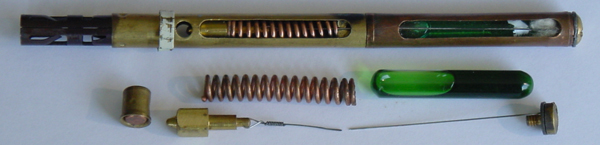

A Pencil for Hitler

The list of devious innovations that came from MD1’s workshops is substantial. Some were not offensive weapons per se; Clarke invented the “Great Eastern Ramp,” a bridging tool attached to a tank that used rockets to shoot ramps over obstacles. But almost everything that came from MD1 was designed to blow up, or to trigger something to blow up. The time pencil was a self-contained timer and detonator for larger charges, using either the action of acid on metal or the deformation of a lead alloy under spring tension as the delay mechanism. A time pencil was used in the plot to assassinate Hitler in 1944; it operated as expected, but Hitler was shielded from the brunt of the explosion and survived.

The lethal hacks from the fertile minds of Ministry of Defence 1 became products that were manufactured in the millions, and the lives taken by their explosions are probably uncountable. The grim playthings from Churchill’s Toy Shop and its equivalents on all sides of the war were engineering solutions to the awful problems presented by total war. Our hope is that now and in the future we can unlock the kinds of research and development leaps shown during these times to solve the world’s problems without having armed conflict as the motivation.

Five and dime? In England? The UK Woolworth’s advertised, “Nothing in these stores over 6d.” Threepence and sixpence, more likely.

Sort of like “Poundland” today…

That’s not the only mistake. I suspect he may have used wiki-fiddlerland as one of his sources.

Eww competitive cultures with disproportionate defense spending.. Oh wait that’s everyone who even has something remotely resembling commerce and GDP..

Thruppence

Thrupennybit and a tanner.

I would argue that war does not stimulate creativity any more than any other problem. It may seem like it does because of the cost-plus resources at play, and the ability for, as the article notes, governments to control individuals in more direct ways.

Going into space while not war directly was certainly a product of an antagonistic relationship between two countries.

This is absolutely true. Just look at what happened when the Soviet Union fell. Complete grind to a halt.

We have lots of lofty, rose-tinted explanations of our actions in that time, but we must realize that we basically did it all to rub it in someone else’s face. To prove we were better and they were inferior. Out of fear that they would do it first.

Friendly rivalry in small scale can be just as motivating. I don’t have to hate the other team. It’s just that when the leading contender can lounge around on its laurels because he hasn’t seen any competition in ages, you get Tortoise and the Hare. And we all know who wins that race.

Sports teams and hooligans.

Indeed.

The entire American space program was initially driven by their obsession with beating the Soviets. An obsession made worse by the fact that the Soviet’s did do it first in many areas. First satellite. First man in low earth orbit. First spy satellite :)

Add in all the other things like first nuclear powered submarine, etc…

The USSR was the first to launch a nuclear powered submarine??

Yep. Not an operational sub of course, ‘just’ a prototype :)

Sadly most of the records appear to have been ‘lost’.

I’m not sure, I think that non-confrontational people could also use the unspecified tension in the air to get things started and funded without ever really being interested in showing off to the (perceived) enemy.

Just a vague notion is enough.

I guess it could be argued, but it also seems overly simplistic to discount the emotional and intangible weight of war. People get tied up in war in a way they wouldn’t get tied up in economics, at least in my unscientific opinion. Of course the economy causes lots of emotional and intangible effects on people as well, but war has a hugely powerful effect.

And in war…

economics (i.e. national debt) takes a back seat. After all, if you lose the war, your economy is ruined anyway.

Enough propaganda & actual threat to your existence definitely spurs people to work, and loosens up the purse strings of the government. Whether creativity (if you can measure it) increases under war times more than under peace time, many jumps in technology can be linked to conflict.

Indeed. That’s why even in fiction there’s an alien as a focal for conflict in which otherwise conflicted groups unify to achieve a goal. A tricky alien could even use that to advance human society into a better state without us realizing it.

Mr. Woolsey:

“Nothing renews your appreciation for the military like the threat of invasion from life-sucking aliens.”

Indeed.

For it’s Tommy this, an’ Tommy that, an` Chuck him out, the brute! ”

But it’s ” Saviour of ‘is country ” when the guns begin to shoot;

Rudyard Kipling

Evidently that threat isn’t enough to help Trump getting funding for his ‘wall” ;)

A bit risky.

Look at what happened to the Persian empire when it ‘clashed’ with that rather fractious bunch of chaps from what’s now Greece. The city states had spent so much and effort fighting each other that their ‘troops’ were better than anything the Persians could field.

Competition breeds innovation.

Sometimes that competition is on the racetrack, sometimes on the sporting field, sometimes in geopolitics, and sometimes in the battle arena.

The battle arena tends to have the bigger budgets though.

So you dispute genetically hard-coded survival instinct as a motivator for innovation? For crying out loud it motivates species to EVOLVE. Doesn’t get more hardcore than that.

My head is hurting even thinking about someone actually thinking war doesn’t drive innovation and creativity at the highest level because the stakes are at their highest. Do they not have history books in your commune?

Let me blow your mind…you can acknowledge that war drives innovation and creativity without condoning, promoting, or otherwise being positive about war itself.

We’d probably be at the Apple II stage of computing if it wasn’t for war. The Internet itself, the greatest conduit for creativity, innovation, and collaboration in human history exists, not because of Al Gore, but because DARPA wanted to preserve military communications during a nuclear war they were so afraid was coming during the Cold War. Colossus beat ENIAC into operation by 3-4 years even though that was kept a military secret into the 70’s.

We went from the Wright flyer to the Moon in only 65 years, largely because of constant war time advances. Hell, the space program itself was largely cover for ICBM research. The early lift platforms (eg Mercury/Redstone) _were_ ICBMs.

Like it or not, war has been, throughout history, mankind’s biggest driver of creativity and innovation due to it’s underlying biological imperative of survival. And that’s leaving weapons out of it. Machines, vehicles, food production, chemistry, biology, medicine, surgery, engineering, modern cars and highways, communications….the list goes on. All accelerated because of war.

Anyway, just because war sucks doesn’t mean you should pretend the innovations that come out of it don’t exist.

“Nothing brings out the worst in humanity like war. Perversely, war also seems to exert an opposite if not equal force that leads to massive outbursts of creativity, the likes of which are not generally seen during times of peace. ”

AT&T and Bell Labs. No war involved.*

*except of the pocket book kind.

Ma Bell was a substantial military contractor. Well after the sale of the rest of the company (Alcatel-Lucent at that point) to Nokia, the military branch remains firmly in the US and using the Lucent name. Or at least part of it. I don’t know, they go to work in the morning, come home in the evening, and don’t go into any detail. In the cold war they ran rather specialized communications between various military installations, and for all I know they still do at that site.

Also, they made a compact AM transmitter and receiver pair (not actually a transceiver, strangely) that was rucksack portable (not an entire backpack). I used to have a surplus one – what was then Western Electric was surplussing them. Olive Drab. Odd little tubes with 1.5V filaments. They would work 80 meter phone, but weren’t exactly great.

I think they’re called L3 now, but I may be wrong.

Nope, I don’t know where I got that idea.

Sure Bell was a substantial contractor, but I believe it was a quest for a replacement of the vacuum tube that drove solid state research. Telephone service was what was drove developing improvements in the vacuum tube, The drive to improve telegraphy and/or telephony drove peacetime innovation, along with motor vehicles. Not to mention the electrification of industry and homes. Much of that existed before wartime applications where found for the technology.

Good ol’ British ingenuity. I miss the days of fixing up ancient Triumph and BSA motorcycles with my dad. They’re wonderful machines in many respects. I notice that all these inventions leave out electrical components. Too early for that? Or was it because of Loose Unsoldered Connections and Splices: LUCAS, Prince of Darkness! I carried bags of spare bulbs in my pocket–which in those days served double-duty as fuses–for many, many miles because of you.

Once again, love the cover art!

For those interested, look up Charles Fraser Smith, the man Fleming allegedly based Q on. He produced some wonderful devices, even today I think we can all stand to learn a thing or two from his mindset.

(Wikipedia). …described as “scholastically useless except for woodwork and science and making things.”

I guess colleges have had their share of intellectual elitist snobs for quite some time… Seems like a lot of histories best thinkers, innovators, and “doers” have received similar critiques…

I would hazard a guess that “scholastically useless” referred to not giving two hoots about Latin or Ancient Greek, the “science” part alone would be considered plenty “scholastic” enough for today’s world.

Absolutely however back then I would say there was more a culture of allowing such people to flourish vs today where you must have the stupid bit of paper that says you managed to sit and read books and remember things for 3 years and cost you a small fortune to achieve. It’s only in the maker community today do we see such people able to flourish and share their work.

Winston Churchill, The Greatest Man of the 20th Century.

Time for people to brag that their nations only have a fraction of the military spending that is higher than what is spent on improving culture and society..

Can you ‘improve culture’ with money?

Short answer – yes. Artists need to eat. Longer answer, yes but you need to know what you are doing and that is the hard part.

a homeless population of millions is a nice little nuance..

“Perversely, war also seems to exert an opposite if not equal force that leads to massive outbursts of creativity, the likes of which are not generally seen during times of peace. ”

Nothing so concentrates the mind and knowing you’re going to be hanged in the morning. Necessity may be the Mother of invention but the Grim Reaper can be a mean mother too.

Wow, I never knew the time pencil was a british invention. They are listed in the WWII OSS catalog of agent’s equipment (BTW reprinted as a fascinating book, which I have – maybe there is a PDF of the catalog out there?) but of course no mention of the origin of the device.

Interesting https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0ahUKEwiWpNGn6ZzZAhVEbKwKHcFoCRUQFggpMAA&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cia.gov%2Flibrary%2Fpublications%2Fintelligence-history%2Foss-catalogue%2FOSS%2520catalogue.pdf&usg=AOvVaw3Si1vnNMufFwjC9oU1Oog2

But it took another thirty or so years before the finally perfected the weaponized joke… https://youtu.be/ienp4J3pW7U

misleading headline picture :(

talk about the lazer/rocket launcher the mk1 guy on the right is holding

Greed and Revenge, as motivators for human behavior, have rarely gone out of style.