So far in this series, we’ve covered the absolute basics of getting on the air as a radio amateur – getting licensed, and getting a transceiver. Both have been very low-cost exercises, at least in terms of wallet impact. Passing the test is only a matter of spending the time to study and perhaps shelling out a nominal fee, and a handy-talkie transceiver for the 2-meter and 70-centimeter ham bands can be had for well under $50. If you’re playing along at home, you haven’t really invested much yet.

The total won’t go up much this week, if at all. This time we’re going to talk about what to actually do with your new privileges. The first step for most Technician-class amateur radio operators is checking out the local repeaters, most of which are set up exactly for the bands that Techs have access to. We’ll cover what exactly repeaters are, what they’re used for, and how to go about keying up for the first time to talk to your fellow hams.

Could You Repeat That?

Time to face some cold, hard facts about amateur radio: that spiffy new Baofeng radio I recommended last time as a great starter radio is actually pretty lame. That fact has little to do with the mere $25 you spent on it, or $40 if you opted to upgrade the antenna. It’s a simple consequence of physics: a radio that transmits at 5 watts will only have so much range on the VHF band, and even less on UHF. Even if you buy a more powerful HT, or invest in a mobile or base-station rig running 50 or 100 watts, the plain fact is that direct radio-to-radio contacts on the same frequency, or simplex contacts, are difficult on VHF and UHF because those bands are really best for line of sight (LOS) use.

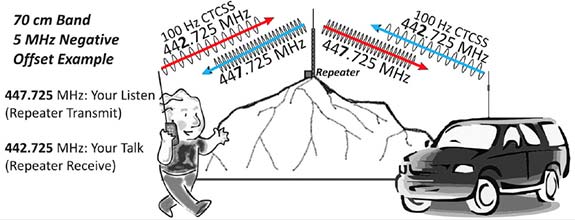

That’s not to say that hams don’t use their VHF and UHF rigs for simplex communications, of course. Many hams like to see just how far they can push their signals on these bands, building big Yagi antennas and finding mountain peaks to operate from. But for general use around town, most hams rely on repeaters to extend the area they can communicate over. Repeaters are simply transceivers set up to receive signals on one frequency and transmit them on another at the same time, with the help of a device called a duplexer. This simultaneous reception and transmission gives rise to the term duplex communications, the general term for operating on a repeater.

Repeater usually transmit at a much higher power than an HT or even a mobile rig can manage, and they usually have the advantage of being located on a mountaintop or some other elevated place to gain the furthest possible radio horizon as possible. This arrangement vastly increases the area that you can cover with your tiny HT. Depending on how the repeater is sited and what sort of antenna it has, you may be able to cover hundreds of square miles, as opposed to perhaps a few miles radius under ideal conditions, or a few blocks in the typical urban or suburban setting with lots of clutter from buildings and trees. What’s more, some repeaters are linked to other repeaters either through backhaul connections, often via the Internet but also sometimes through powerful LOS microwave links. In these systems it’s possible to use a puny HT to talk to another ham over hundreds or even thousands of miles. It’s actually pretty cool.

Welcome to the Machine

So where are these repeaters, and how do you start working them? The first question is easy to answer: they’re everywhere. Look at any tall building, mountaintop antenna farm, or municipal water tank, and chances are pretty good there’s a ham repeater there. But being able to work them means you need to know exactly where they are, to be sure you’re in range of the repeater, or “the machine” as hams often refer to it, as well as the frequencies it operates on.

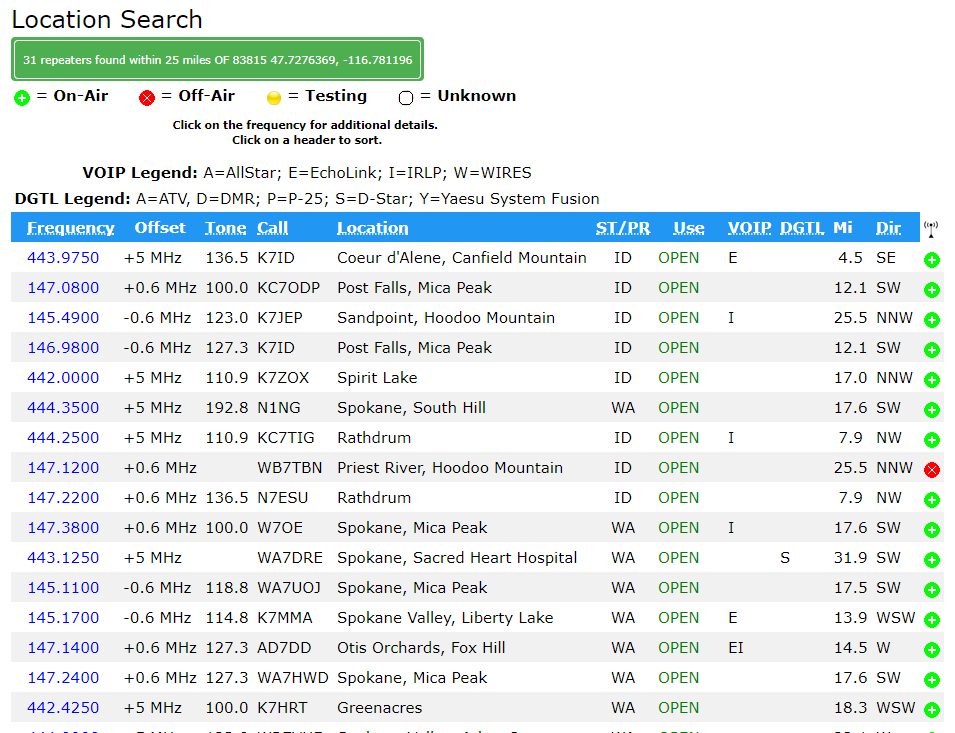

Luckily, there are online guides to help with that chore. RepeaterBook.com is usually the first place hams go to find machines in the area. There you can search by state, county, or city, or even via a map, and find what repeaters are available. They’ve even got a handy road search, so you can get all the repeaters listed as within range of a particular highway; that’s really handy for road-trip planning. Here’s what comes up for VHF and UHF repeaters when I search within 25 miles of my location, or QTH:

The first thing you’ll notice is that several machines at different sites have the same callsign. For example, K7ID runs a UHF repeater on Canfield Mountain and a VHF machine on Mica Peak. Both are LOS to me, and I can easily hit them with an HT. The frequency listed in the first column is the transmit frequency of the repeater. Your HT will need to be set to this frequency to hear what’s being said. Your radio will also need to be programmed for the correct tone, listed in the third column. That tone is an audio frequency signal known by a number of different trade names, but generically as continuous tone-coded squelch system (CTCSS). Your radio is capable of adding this sub-audible tone to your transmission; the repeater will only “open up” to transmissions that are correctly coded. Some repeaters have no tone coding, others have different tones for receive and transmit. When doubt, try to find out who runs the machine – most, but not all, are run by a ham radio club – and see if you can look up instructions on the web.

The offset shown in the second column is perhaps the most important bit of information. Recall that repeaters transmit and receive on different frequencies, and that they’re listed by their transmit frequency. The offset tells you what the repeater’s input frequency is, which is the frequency your radio will need to be set to transmit on. For example, the machine I most often used is the K7ID machine on Mica Peak. It’s at 146.980 and shows an offset of -0.6 MHz. That means that my radio has to be set to 146.380 MHz transmission frequency. VHF repeaters are usually 0.6 MHz, but could be plus or minus depending on which part of the VHF band they’re in. UHF repeaters usually have +5 MHz offsets.

Note: I’m not going to cover programming your radio, because there are plenty of guides online that do a better job than I can. DuckDuckGo is your friend.

Casting the Net

Once you’ve found your local repeaters and programmed your radio, it’s time to get on the air. My advice is to spend the first few days just listening to one or more repeaters. Activity levels vary – some machines are hopping all day, and some are barely used except during the typical commuting hours. When you hear a conversation, try to get a feeling for the culture of the repeater. Every group of hams has a culture, and as we discussed in the first installment of the series, it’s not always a healthy culture. My local repeater belongs to the Kootenai Amateur Radio Society, as friendly and as inviting a group of people as I’ve ever heard on the air. After listening to them chat for a few weeks, I was more than ready to reach out to them.

But first, a word about kerchunking. If you want to know if you’re in range of a repeater, you can test it out. Most repeaters have a “squelch tail” that keeps the repeater on the air for several seconds before going back to sleep, and this can be used to check if you’re in range. Some repeaters even identify themselves, either with a synthesized voice or Morse code when they “wake up”. So you might want to ping the repeater.

Kerchunking, or transmitting into a repeater without identifying yourself, is one of those bad habits that everyone seems to have. But FCC part 97 rules, which cover the amateur radio service, require operators to transmit their call sign when they start a transmission. So don’t kerchunk; a simple identification like “This is KC1DJT testing and clear” will suffice. Nobody is likely to take that as an invitation to chat, but they might give you a reception report.

Once you’re feeling confident enough, try making a contact. I highly recommend checking out the local traffic networks. Hams pride themselves on having the skills and equipment to communicate in an emergency, but that means little without practice to keep everything sharp. Nets allow hams to practice message passing skills and to test their gear on a regular basis. My local group has a network check-in every night that follows a standard script and usually attracts about 30 check-ins. Here’s a sample from a recent check-in:

I’ve become a regular on this net and a few others, mainly because I want to practice, but also to get over my mic shyness. There’s another reason too – I want people to recognize my voice and callsign. If there ever is an emergency in my area, I feel like it’ll be easier to pitch in or to get help if I need it if people hear a familiar voice.

Next Time

Over the next few installments, we’re finally going to get to what I think ham radio is all about at its core: homebrewing. We’ll be building a few simple projects to make that cheap HT a little better, and also build a few tools to help run the shack a little more efficiently.

Read more from this series section needs updated with additional links. Each time I go to the first it says… ‘Last week…’ something, something.

Sorry, didn’t have the first article in the series properly tagged for inclusion on the list. Fixed it, thanks for the heads up.

Also fixed the status of the YouTube video – it was still marked as private when we published the article. You should be able to watch the riveting action of a traffic net check-in now ;-)

GrammerNZ: It never pays to be bothered by improper grammar. A lady or gentleman of the 19th century would likely find most of what we say today to be improper. Language evolves, mainly due to laziness. You might as well spit into the wind, as try to correct this.

Nitpick, only pointed out because it’s a question on the exam, and I wouldn’t want anyone to get it wrong: The FCC rules in section 97.119(a) require hams to transmit their call sign at least every ten minutes and at the end of a communication. There is no regulatory requirement to transmit ID when you start transmitting, though custom and protocol often encourages it. Anyway, you’re right about kerchunking — even short test transmissions must be identified.

Looks like you’ve killed RepeaterBook. Oh well.

One thing about kerchunking — kerchunking a d-star repeater is not completely anonymous, your radio will transmit your callsign. It’s also common on reflectors (something you will probably cover along with mmdvm stuff) to consider a silent kerchunk as the equivalent of a CQ call.

Kerchunking on DMR is the same – your callsign gets transmitted when you key up.

Not really. DMR doesn’t send callsigns, it sends DMR ID’s. While an ID is linked back to a callsign, it is not the same thing. If you don’t have the current DMR ID database loaded into your radio (and who can keep up?), all you’ll get is their DMR ID.

I remember back in the days before mobile phones were prevalent, a lot of the repeaters had an “Autopatch” feature that would tie into the phone system and let you make a (often local only) phone call through the repeater. Once my dad and I were driving around and he had his radio in the car since we were going camping that weekend with my grandparents, and he wanted to make sure the radio was functioning properly. The radio crackled and we heard someone request an autopatch through the repeater, and then heard the phone dial, and someone proceed to order a pizza. Dad recognized the callsign and the voice as someone he worked with, so the next day at work he asked him how his pizza was and got a good chuckle like how did you know we had pizza….

If you are really feeling adventurous, there are some repeaters in the range of 125-250 miles LOS that you can work with an HT and a good antenna (though an eggbeater or handheld yagi is even better). The fact that they happen to be in Low Earth Orbit may mean you need to take doppler into account however.

There is nothing quite like working over a satellite link. Great fun.

Yeah, on tap for a future article is a tape measure Yagi to make ISS contacts and using the AMSAT repeaters.

Cool. I’ll be looking for it.

I had a fence wire and groundwire U/V yaggi with a duplexer just a few coils and caps and it worked fine with some 75ohm cable tv coax to an old Alinco DJ-580e.

Other than ARISS though what else can you still(or rather now) hit with an FM HT rig?

I am surprised there are not any SSB HTs like there used to rarely be or have it as a mode for the bent pipe birds now, maybe even throw in some real microwave modes rather than needing up & down converters and a FT-417 size and priced minimum rig (or a DIY).

TLDR – 1) No, it’s not the power level, it IS the antenna and even more so the height off the ground. Chasing higher power is a recipe for causing interference while still not talking much farther.

2) The idea that a beginner with an inexpensive handheld is going to be the most satisfied by focusing on repeaters…. Very true, that is good advice. Don’t be afraid to tune off the repeater and try for some simplex from time to time. I would especially suggest (in the US) the 2-meter calling frequency of 146.520. If you try there from time to time you probably will not find anyone most of the time but if you keep at it eventually you will. Then you can have a contact that relies only on your own equipment and that of the person you are talking to, no intermediary. It’s kind of a nice experience if DIY is the interest that brings you.

Long Version –

“It’s a simple consequence of physics: a radio that transmits at 5 watts will only have so much range on the VHF band, and even less on UHF”

You might be surprised. I’ve made it over 100 miles using a 5-watt handheld. That isn’t special, others have done better including through satellites much farther away due to height than I was talking out at that power level.

It really is your antenna more so than your power output that dictates your range. You are right though, simply putting a bigger ducky on your handheld isn’t going to make it suddenly talk around the world. It’s the height!

The greater problem at VHF and UHF frequencies is that radio travels in a straight line but the Earth’s surface is curved. At lower frequencies it might bounce off upper layers of the atmosphere and back to the ground many miles away. At VHF and UHF it just keeps going off into space over the heads of those distant people you might want to contact.

Light also travels in straight lines. (Technically light is just radio at a higher frequency) That’s why you can only see for so far. Objects beyond the horizon are below the ground in front of you due to the curvature of the Earth. That’s called line of site and it’s also how VHF/UHF radio works, line of sight. So, if you want to talk farther the best thing you can do is to put your antenna higher. So how high is your typical handheld radio antenna? Well you are carrying it so how tall are you? Not very compared to the distance to the horizon huh?

So how did I talk 100 miles with a handheld? Even at VHF and UHF there can be weird temporary atmospheric conditions that reflect signals allowing you to talk to unexpectedly far places.

And what about power? More power will help some. Your signal will bleed just a little beyond line of site. More power might increase that just a hair. Objects on the ground might absorb your signal. More power might get through them better. It really doesn’t do much though. That’s a common thing trap for new hams, not satisfied with their range and always trying for <Tim Allen voice>More Power</>. Instead of getting more range it just ends up increasing their chances of interfering with their neighbors tv, stereo, etc… and increases the chance of blowing up their own transmitter if their antenna isn’t tuned well.

Why doesn’t more power help? You have to understand, as the power from your transmitter travels farther from your radio it is spreading out thinner and thinner. To state it mathematically the power intensity from your radio follows an inverse square law as you travel farther from the source. So, at a given point x miles away how much power is there from a high power super duper ham transmitter? Bupkis! So if that transmsitter is turned down to 1/2 it’s power? Then you get 1/2 of bupkis! And what is the difference between bupkis and 1/2 bupkis? It’s bupkis! Radio only works because the receiver is very sensitive to tiny little signals. You don’t need much.

I have skipped something here though, directionality. By using an antenna that focuses it’s signal in one specific direction you can lessen the rate that it spreads out. Your signal strength is still dropping via an inverse square law but the multiplier is lower so it can be much better.

Directional antennas aren’t really a common thing on handheld radios though. You would have to turn it every time you face a different direction!

Another thing you skipped is that power only helps others to hear you. It does nothing to help you to hear them. Antenna gain works in both directions. So if you only want to talk to others who have 100W+, go ahead and upgrade your tx. But if you want to talk to others operating on low power, nothing beats a better antenna, and as you say, height. Keep in mind that signal paths and passive components (such as antennas) are reciprocal – they work exactly the same in both directions. So if shrubbery attenuates your signal by 10 dB, then it also attenuates the signal you’re trying to receive by 10 dB. The bottom line is, assuming receiver sensitivities are the same, there is nothing to be gained by having more transmit power than the station you’re communicating with. There is a common misconception, that repeaters need lots of power to cover more area. They don’t. If you do the math, you’ll know this. The purpose of repeaters is to reach more area by filling shadows caused by terrain. Beyond a certain minimum power, terrain and height almost exclusively determine their area of coverage.

And just one more thing: directionality does not lessen the rate that it spreads out. You even say so in the next sentence. It just concentrates your power (and your receive sensitivity) in a particular direction.

Agreed, I work an local city’s Christmas Parade providing communications every year, and the majority of us use HT’s on simplex frequencies with net control on an mobile unit as a base station with an antenna on an pole. If the station on the route has an LOS to the net control antenna, they can usually run 1/2W and be heard. I usually am put over by the band staging area with multiple buildings between the antenna and me, and I have to run 5W for them to hear me. If I stand in the same area but link to an local repeater on the mountains nearby (approx. 5000ft elevation) then I can run 1W or less and still link in.

Comments are now being processed by Facebook??? What manner of sorcery is this?

A few years ago, a company I worked for used a repeater for his business radios.

AIR, Los Angeles to Texas was common.

Butt, WTF do I know?

Could have been some sort of linked repeater system using the Internet for backhaul.

Actually you are likely talking about one of a couple of systems that while being commercial radio systems were dreamed up and built by hams myself and a couple of other guys in particular. Repeaters have been around in the ham world for many years starting first in A.M. 2 meter variants even before squelch was a real thing. Back then you kept your volume low until a signal came on the air then turned it up to communicate. Lord forbid you say what a concept. Yet this is exactly how most HF communications is conducted today. For years aircraft had no squelch then pretty much like on the original A.M. Marine band, and CB it was ignored and simply not used everyone just accepted the background noise as a cost of operation. The first good squelch in fact the first real squelch was invented by the fsmous Ham Don Stoner and was adopted by A.M. users and F.M. alike. The big BatWing Motorola was the first to make a real improvement on the design for F.M. and the commercial world. Soon after came Collins and King in the aviation world for A.M. systems and many many advancements in noise reduction were from the lowly world of CB because that is where the consumer demand was. I say all that to say this without Hams repeaters would not have existed at least not for a long time later than they did, so yes there were interconnected commercial radio systems some of the first being the RailRoads. They often along with State Patrol radio systems required great distance radio coverage. A large majority of this was accomplished on and by 72 MHz links and some Microwave links but we tend to forget there was no internet or digital backbone with I.P. to accomplish this so often it was done by plain old wireline. Sometimes that was a Telephone circuit (Thank you Maw Bell) other times it was simply a dry pair of wire D.C. Remote Circuit. I’ve seen a lot of changes and innovations in my life and participated in as many as I possibly could. When as a student and young Scout I carried old battery powered radios of various kinds some old Military others retired from the Railroad all modified to suit my purposes as Ham Radios. I lived and loved through the hay days of the great 2 Meter revival that was brought on by F.M. and Repeaters then I like others suffered through the High Band CB days and the decline of repeater use. But what produced the first 2 Meter upheaval is the same that produced the Second and now the Third is CHEAP Equipment! The first was Cheap WWII surplus radios and parts to build and modify. The second was Cheap Wide Band F.M. commercial equipment. Now the third is a couple of factors again a narrow banding of Commercial Frequencies as well as Very inexpensive radio especially from China including inexpensive ways for a new Ham or any Ham to get involved with Digital Radio. Lucky for us most radios are backwards compatible to operate on standard F.M. as well. I’ve said a lot about what has driven us Hams to do the things we have done and often innovations undreamed of have come of it. I was told years ago by one of the wisest men I ever knew that like Paul Harvey always said one needs to know the rest of the story! One day he reminded me of an old adage that goes “Necessity is the mother of invention!” I replied I was aware of that. His comment was dis I know who Inventons Father was? I was blank! He replied I thought so, well let me tell you the rest of the story. Invention is by almost all accounts a bastard, and his Father is Laziness! I was stunned for a second as he continued on. Far more things have been invented by people to get out of work or do something in a less expensive way! Hams are the Kings of doing things the easiest and the Cheapest way possible. Not because we are just cheap basrards but nature but we try to squeeze every drop out of life! Without us Al Gore could never invented the InterNet! LOL CellPhones wouldn’t exist, neither would the computers you are reading this in right now. I for one am glad to see the revival of the Repeater Culture, I’m glad for my parents and myself since we enjoyed the earlier ones. I’m glad for my children for they will get to experience the joy I found. But mostly I am glad for my grandchildren because it will afford them opportunities some of which I cannot even conceive! Laurin Cavender WB4IVG

Laurin, how are you. I read your description of your Yaesu FT-301d. Back in 76 my dad who was also a radio engineer bought one with the FP-301d and monitor YO-100. I was 18 and helped him put up a 80 ft antenna. We had about six different antenna’s thru a rotary switch. we enjoyed many evenings sometime all night and talked with people as far as Russia. Many memories and my dad recently passed and I now have all his setup. In todays world with new technology and in electronics I would like to get your recommendation on an antenna. That is all I lack, I have a 50 foot mast for a yagi antenna. I need to refresh an d get a license again but need to get an everything together for a complete base station. Of course a 50 ohm and 10 t0 160 meter. Any response would be appreciated and have a great day.

You can hack on those Chinese radios to make them more selective to reject interference and stay in band better.

Also as above anything ‘tuning’ your antenna is burning a percentage of your xmit into thermodynamic loss as well as wasting incoming signal, a cut to tune and nt an electrically tuned wire or whip antenna is always going to be best, the other hacks just play with directionality or focusing/reflecting a signal.

Instead of kerchunking, you should open your squelch and listen for a couple of seconds and then transmit with your callsign (Richard/AG6QR is correct about the requirement in the US). This is a check to ensure that you haven’t left the volume turned down and transmit over someone else’s ongoing conversation.

Hey, guess what yesterday was. I sure didn’t know until late in the day. I had just bought my first ham transceiver (a 2-band handheld NOT from Baofeng) two days ago, and had it scanning the local repeaters around Portland on 2m and 70cm, and one repeater on 440.400 was just lighting up. Turns out, it was WORLD AMATEUR RADIO DAY. I learned this because of the monstrosity that the HT community has become, with the help of not just repeaters, but also all manner of different RF/Internet bridges, such as IRLP and Allstar. So people calling in from Florida, England, and India, all sounded the same as others in Portland. And no, I don’t understand the culture of “nets”. People call and “check in”, and get logged. Somewhere. And while QSL cards appear to still be a thing, what does it MEAN, when you don’t even have any idea what path your communication took? So yeah, I checked in, and actually got heard on the second try, and even asked for a QSL card, but I still have no idea what it MEANS.

I mean, for the moment, it appears that since this whole hybrid Internet/radio thing is driven by hams, so the equipment I’ve seen is all about creating nodes that connect radios to Internet connections, but it seems like it would be easier to just cut out the RF end and connect to these “nets” with your sound card. Which means that you could participate in amateur radio without having so much as a $25 Baofeng. Somebody please explain it to me.

Better check those fcc rules again last time I looked it states that ID is required every 10 minutes and at the END if your last transmission. So if you kerchunk the repeater, you must ID because it is you last transmission.

Yes you must ID but it is not technical required at the beginning