If for some reason I were to acknowledge the inevitability of encroaching middle age and abandon the hardware hacker community for the more sedate world of historical recreation, I know exactly which band of enthusiasts I’d join and what period I would specialise in. Not for me the lure of a stately home in Regency England or the Royal court of Tudor London despite the really cool outfits, instead I would head directly for the 14th century and the reign of King Edward the Third, to play the part of a blacksmith’s wife making nails. It seems apposite to pick the year 1337, doesn’t it.

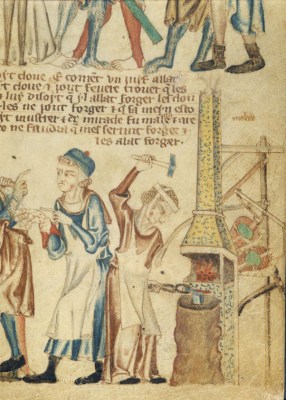

Why am I so sure? To answer that I must take you to the British Library, and open the pages of the Holkham Bible. This is an illustrated book of Biblical stories from the years around 1330, and it is notable for the extent and quality of its illuminations. All of mediaeval life is there, sharply observed in beautiful colour, for among the Biblical scenes there are contemporary images of the people who would have inhabited the world of whichever monks created it. One of its more famous pages is the one that caught my eye, because it depicts a woman wearing a blacksmith’s apron over her dress while she operates a forge. She’s a blacksmith’s wife, and she’s forging a mediaeval carpenter’s nail. The historians tell us that this was an activity seen as women’s work because the nails used in the Crucifixion were reputed to have been forged by a woman, and for that reason she is depicted as something of an ugly crone. Thanks, unknown mediaeval monk, you really don’t want to know how this lady blacksmith would draw you!

This image and the history behind it have intrigued me for years, to the extent that I’ve eyed up more than a few seven-century-old metal fastenings in my time Until recently though I’d never had a go at making my own, but with a weekend at Hack42 and a portable forge to play with it seemed like an opportune moment to do my nails.

A Brief History Of Nails

The first nails were entirely hand forged from a piece of wrought-iron bar into a tapered point about 6″ (150 mm) long, with a head hand-formed by hammering flat a piece of untapered original stock. These are the nails that the Holkham blacksmith is making, as well as those that I am interested in. There are special dies for forming nail heads into which the point is inserted so the head can be hammered flat, but it is also possible with a little skill to hammer the end flat upon the edge of the anvil.

The shape of a nail changed little from Roman times until the first nail-making machinery appeared in the 17th century. Even then, the first machines were designed only to speed up production of these traditional nails, the finished product is very similar to its predecessor. It was around the end of the 18th century when the first significantly different nails emerged, the cut nail, so-called because it was formed as a tapered piece cut from a sheet of metal. These retained the four-sided taper of the hand-forged older nails, but had a much more uniform look. The modern round wire nail appeared in the second half of the 19th century, and because it could be made by automated machinery it quickly displaced the cut nail.

In a sense it’s difficult to properly replicate the hand-forged nails of old in the 21st century because of the lack of the wrought iron they were made from, but the steel nail I can make is functionally equivalent even if it requires a lot more effort to forge. There’s no sense at all in forging a mediaeval nail, but if that were the only criterion I suspect half the awesome stuff we feature on Hackaday would never see the light of day. So picking up a piece of rebar, it’s time to head for the anvil and give this unexpected project a go.

Making the nail

The idea is to take a piece of rebar and forge it to a tapered point with about half its diameter, then cut it off about 10 mm to 20 mm above the start of the tapered section. The resulting “slug” of metal can then be hammered flat to form a nail head, and the result should be a usable nail.

Drawing out the tapered point is a very straightforward process of hammering equally on all sides that shouldn’t detain any smith for long. I tried one brought to a round point and a couple of square points, and I am told that the square one makes for a better nail. The head, by comparison, was not so straightforward, and of the three I produced I didn’t manage to fully form any the way I’d originally hoped to on the edge of the anvil alone.

The idea is that I should be able to take my “slug” of metal on the thick end of my taper, hold it against the edge of the anvil, and hammer it at an angle while continuously turning it such that it flattens out. In practice I either didn’t crack the method of holding it against the anvil or I hit it at the wrong angle, and I had to finish it in the leg vice in which I was able to hammer directly down upon it. The mediaeval lady has no leg vice, so in that I failed. Another attempt at a head involved flattening the slug into a spatula-like shape, before bending it at right angles and folding it backwards and forwards to make a head. A success, but not how the real mediaeval nails would have been made.

So having never made a nail before I was able to learn something of the technique and knock out a few of them with relative ease. It’s not quite a truly authentic nail, but I’m getting closer. If there’s one place I’ve gone wrong though it’s one in which the lady in the Holkham Bible would have beaten me hands-down. Each of these nails took me between a quarter hour and twenty minutes to make, while she would have been able to knock out one a minute. Maybe I’m not quite up to historical recreation standard after all.

Header image: © Martina Short, used here with permission.

> Maybe I’m not quite up to historical recreation standard …

… yet. Do it for several weeks and you will be up to standard :)

The King of nails was the “Door Nail”. The door was very important for security and required a strong short nail with a large head. It would be clenched to hold the door boards strongly together.

“There’s no sense at all in forging a mediaeval nail”

Re-roofing Notre Dame?

B^)

You think they are going to trust millions in renovations with a roof held together with primitive nails? There is probably better nail technology now…

millions? try billions

You under estimate the lengths some groups will go for historicities sake. That’s not to say they won’t use modern materials but very often period techniques take priority over modern ones. The old ways lasted centuries afterall, they’re not appreciably inferior.

I imagine it will be a mixture of modern and old-world technologies.

The actual super structure will almost certainly be modern construction…we probably couldn’t duplicate the required craftsmanship, too many secrets lost to time.

The facade will probably be a reasonable approximation of old-world techniques and anything especially iconic (not that the entire structure wasn’t) will probably be “no expense spared” type craftsmanship.

Actually, old style cut and forged nails hold better than modern wire nails. https://toolsforworkingwood.com/store/blog/324 They were also hugely expensive, to the point that when a building burned one of the cleanup tasks was to sift though the ashes to recover the nails.

I suppose the Romans recycled their Crucifixion nails. BTW, there is a 90’s Grunge-Alternative band named ‘Nine Inch Nails’. I’m wondering if that was the standard length used for it. Makes perfect sense as the impaled wrists would not work their way off as would a shorter nail. A good nailer would also drive it in and thru at an upward angle to ensure no slippage.

This actually came up in an archeology course I took, decades ago. The shortest crucifixion nails ever found were about three inches long, and the longest were about six inches long. Fur further info: https://www.bing.com/search?q=how+long+was+a+crucifixion+nail&form=APIPA1&PC=APPD

They’ll use the half-way house of the first nail manufacturing tech, the heads look the same.

Love the smithing posts! Thanks, Jenny!

Thanks! :)

I’m curious about how the nails were being used at the time. Were they a “luxury convenience” type construction tool that was used instead of slower fastener-less building techniques?

They were used in a multitude of ways. One reason why they were square and tapered to a wedge is because they were used as wedges to drive pieces of wood tightly together. The nail would be driven all the way through, and then bent over twice to form a staple which could be driven back into the wood.

An example of the use of these hand-made nails:

https://www.pbs.org/video/the-woodwrights-shop-the-tiny-tool-kit/

Part of the reason for folding the nail point back was to prevent nail theft. They were rather expensive.

Nails made of wrought iron could be cold worked, so a heavy nail could be hammered into a rivet for fixing door hinges or other reinforcements.

The typical medieval construction did use interlocking pieces of wood, such as panels fitting into grooves, but the whole construction would still come apart if there wasn’t anything to fix the frame together, so nails were used in the critical joints, and, because they were new and relatively expensive, they were used as decorative motifs to show what a high-end piece of furniture you have.

A bit of both in my anachronistic opinion.

Wood dowels (aka treenails) worked well for draw-boring timber frames together but for things like shingles & siding, iron nails provide an assembly speed boost while still providing flexibility as wood swells/contracts with the seasons.

It really comes down to the joint in question and how the grain is oriented. Remember at the time you had joinery, dowels/nails, and weather vulnerable hide glue as your options. A craftsman worth their pay would know when you could use each.

Don’t sell yourself short, her first nail probably took as long. Practice is key.

As I recall, there is a tool that looks a bit like a pair of tongs, but with a hole in it to make nails with that I used in my (much) younger days. Basic operation was form the shaft of the nail with a bit of a blob on top, cut off, re-heat the top, drop the shaft in the hole, blob sticks out the top, whack 3 times with hammer to form head, knock out a nail with a head.

Yep, there is such a thing ( the ones I’ve seen are usually a bar though ). It’s called a nail header.

Dammit, I thought this was going to be about free CDs

Only if you make them nine inches long

Jenny, you nailed it..

Both spellings are valid, but the “Medieval” spelling is more common these days.

TIL

And I usually spell words like archaeologist and paediatrician with the aesc.

The nails shown look great, but pretty rough. I wonder if they can be polished.

Though somehow I don’t think that a blacksmith uses nail-polish to make them look better. So… I’m confused

Medieval nails were often tinned to make them shiny on the end.

I wasn’t really covncerned with the finish.

Sometimes I wonder what I would do by myself if somehow traveled in time to prehistoric time. It is sad , but maybe fire, some wood stick tools… Other? No metal, no plastics, no electricity, in fact even no idea how to start with simple calendar…

Oddly there’s an HB book over there that details ways of starting a fire. Who knew one could get a book out of a simple subject?

Jenny made the nail, you just need a Li-Battery to put the nail into and you have a nice warming fire.

“Sometimes I wonder what I would do by myself if somehow traveled in time to prehistoric time.” Probably, like most of us, end up making an interesting little archaeological find, “How did filled teeth get into a 10,000 year old bear coprolite!?”

I once attended a “Rendezvous” (a gathering of people re-living/re-enacting the life of early fur trappers in North America) at the site of an early 19th century Trading Post.

One participant had traded one of his furs (IIRC) for 3 large 16th century Dutch glass beads. As he only needed 2 of the beads for a project, he threw the other one into tall grass. He reasoned it would give a future archeologist a conundrum; (How did a 16th century European artifact end up in a primitive 19th century North American site?).

Not much of a conundrum, happens all the time. The usual answer is “Not in 16C context, someone moved it there later”. Considering that it will be found with 21C pennies, bottle tops and gum wrappers, they’ll even be able to say when.

> (How did a 16th century European artifact end up in a primitive 19th century North American site?).

It happens, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Llygadwy for an example.

“The historians tell us that this was an activity seen as women’s work because the nails used in the Crucifixion were reputed to have been forged by a woman”.

How would they even know? Did the head have a ⚲ symbol*?

*Which BTW is the symbol for copper (iron is Mars). Plus the modern Venus symbol has a bar, the medieval didn’t.

“There’s no sense at all in forging a mediaeval nail, but if that were the only criterion I suspect half the awesome stuff we feature on Hackaday would never see the light of day. ”

If we had an apocalypse which would be easier to recreate?

It goes back all the way to the original sin with Eve tempting Adam, which lead to the other thing, which eventually lead to the crucifixion. It’s an idiom rather than a statement of fact.

Some skilled woodworkers like Christopher Schwarz say that such nails are far superior to wire nails.

Depends on the application. If you’re trying to re-create old furniture, then sure.

But after the enlightenment, nails as fasteners became to be seen as a sort of passé and straight up joinery using only wood was seen as the superior way because it required more skill and planning. It became seen a kind of a cheat, like nowadays when everything is just hot-glued together.

It’s more down to how you use them.

A clinched (bent over / stapled / riveted) nail behaves appreciably different from a wire nail. They serve similar or equivalent purposes in many respects but how they affect the joined wood can matter in some circumstances.

The wedging action of a wire nail is greater than a properly used cut nail, for example.

The joinery example you bring up is interesting because in their peak, dovetails ( and other joints) were hidden behind molding, they wre treated as underwear behind proper clothing whereas in modern times they’re celebrated as a sign of bespoke craftsmenship.

Oddly I have yet to use any of mine as a nail. :)

“If I Had A Hammer” (All sing along)

These blacksmithing posts are very fascinating. Thank you for illuminating such an old and relevant technique. It is important to know where we came from, methinks. I have not worked with steel (except for cutting stock pieces to shape and using them for mechanical stuff, or my miserable welding attempts), but I have built a foundry for melting aluminium. There is something utterly satisfying about working with metal, the heft it provides in comparison to wood makes it so much more tangible in a way I can not describe. I am looking forward to your next post on the subject, Jenny!

Thanks! I need to remind everyone though, I am not an expert smith. I grew up around a forge so it’s something I know a bit about, but my smithing is fairly amateur.

Which reminded me of this exchange from Star Trek IV: The Journey Home

“Spock: Mr. Scott cannot give me exact figures, Admiral, so… I will make a guess.

James T. Kirk: A guess? You, Spock? That’s extraordinary.

Spock: [to McCoy] I don’t think he understands.

Leonard McCoy: No, Spock. He means that he feels safer about your guesses than most other people’s facts.

Spock: Then you’re saying… it is a compliment?

Leonard McCoy: It is.

Spock: Ah. Then I will try to make the best guess I can.”

In other words, I would trust one of your nails, Jenny, over one of mine (had I made any).

Interestingly enough, the nailmaker here failed to do what was usually done in old times: bronzing said nails.

The problem is if you use Oak or other woods, the acids in the wood will rot the iron nails from the inside out. And they’d discolor the wood in bad ways. So you’d bronze them and give them a shiny look all the while protecting them.

But this is a good example of homemade nails.

This is an interesting detail that I never knew and I always wondered how the nails did not actually corrode in the wood but I figured I was overthinking things.

Guess I wasn’t and there was actually a practice to protect the nail and the wood. Very cool.

As someone else pointed out, there is a tool for this, commonly made from old files, called a nail header.

It is a tapered square hole through piece of tool steel with a slight cup at the top and the narrowing taper entering from the outward cup so that you drop a pre-formed nail into this tapered square hole.

The taper both holds the nail at a specific depth and allows it to lock in place as the metal on top is beat over into the head over the shallow cup top of the tool, both creating a slight recess behind the nailhead and allowing it all to release back out if you hit from the opposite side and giving you a perfect nail head.

The shallow come to the back side of the nailhead helps it sink into the wood and fully seat so that nothing can get under the nail.

There is exactly one book I know of on historical nail making that is quite short, Nailmaking by Hugh Bodey, from Shire Library. Ironically well it is about the history of handmade nails up to modern cut nails, there is at a glance no detail init on how to forge a handmade nail.

You have given more detail on that here then the book has, but the book has 36 pages of many eras of historical nails.

Handmade nails are pretty quick to make if you have a nail header tool, not hard. Upsetting the head (smashing metal straight down on top of the taper) is the strongest way to make them.

Excellent series, still, well done!

Soooo, I DAGS:

https://www.blacksmithsdepot.com/products/single-die-tools/nail-headers.html

The purpose here is the smithing technique, not necessarily to make a nail I’d use. But yes.

If you want to see some other medieval crafts being explored, have a google for Guedelon Castle. In the middle of France there are a group of experimental archaeologists trying to build a replica of a 13th Century castle using wherever possible only 13th Century techniques (they do bow to modern Health and Safety requirements for stuff like scaffolding, safety harnesses and hard hats). On You Tube at present there is a five part series from a couple of years ago when three BBC presenters spent one summer season working there as volunteers. The on site blacksmith features a lot, including making nails like these from iron bars. Here’s the first episode

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ydoRAbpWfCU

And if you understand French, here’s the whole five hours edited down to one and a half by cutting out the exploits of the presenters and focussing on the history.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dXoM77KB8h4

This is a serious long term project, started back in the nineties, and expected to end sometime in the next decade (although if they really want to emulate their medieval forebears they should then start on a major rebuild).

Very much so, some fascinating stuff there. I would love to spend a while in their forge.

That person next to the smith seems to have a lot of wounds to their hands. I hope not due to poor blacksmithing habits! I couldn’t help noticing flowing clothes and lack of eye protection, tut tut.

Smallpox? The plague.

Your use of the word “smith” in your comment triggered me! B^)

Causing me to respond with nothing less than a quote by G. K. Chesterton about the name, Smith!

“But of all the examples of this general fact that have recently been called to my notice, there is none more peculiar and interesting than that of the family name of Smith, in which we have a splendid example of the fact that the poetry of common things is a mere fact, while the commonplace character of common things is a mere delusion. For, if we look at the name Smith in a casual and impressionable way, remembering how we commonly hear it, what is commonly said about it, we think of it as something funny and trivial; we think of pictures in “Punch,” of jokes in comic songs, of all the cheapness and modernity which seem to centre round a Mr. Smith. But, if we look at the plain word itself, we suddenly behold a poem. It is the name of a great rugged and primeval craft, a trade that is in the bones of every great epic of antiquity, a trade on which the “arma virumque” have everlastingly depended, and which they have repeatedly acclaimed. It is a craft so poetical that even the babies of village yokels stand and stare into the cavern of its creative violence, with a dim sense that the dancing sparks and the deafening blows are in some way wonderful, as the shops of the village cobbler and the village baker are not wonderful. The mystery of flame, the mystery of metals, the fight between the hardest of earthly things and the weirdest of earthly elements, the defeat of the unconquerable iron by its only conqueror, the brute calm of Nature, the passionate cunning of man, the origin of a thousand sciences and arts, the ploughing of fields, the hewing of wood, the arraying of armies, and the whole beginning of arms, these things are written with brevity indeed, but with perfect clearness, on the visiting card of Mr. Smith. The Smiths are a house of arrogant antiquity, of prehistoric simplicity. It would not be at all remarkable if a certain contemptuous carriage of the head, a certain curl of the lip, marked people whose name was Smith. Yet novelists, when they wish to describe a hero as strong and romantic, persistently call him Vernon Aylmer, which means nothing, or Bertrand Vallance, which means nothing; while all the time it is in their power to give him the sacred name of Smith, this name made of iron and fire. From the very beginnings of history and fable this clan was gone forth to battle; their trophies are in every hand, their name is everywhere; they are older than the nations, and their sign is the Hammer of Thor. “

Just don’t ask a smith about horseshoes, that’s farriers!

“… it seemed like an opportune moment to do my nails.” Shure! Why not women like to do their nails. ;-)

I don’t think you’d want to be a medieval blacksmith. I’ve read (don’t know if it’s true) that blacksmiths were so highly valued that once a town had a blacksmith, he’d be crippled so that he could never leave the town.

Shotgun wedding, before there were shotguns.

Also missing article break :p

Either is appropriate. I guess my use of ae is a hang-up from my education.

Thanks for the blacksmith posts Jenny! I hope you expand on your newly-expanding skill with more posts.

I’ve made some metal things work with a hammer and some propane heat, but those are also super advanced aluminum/steel alloys from the past hundred years. A little harder when you’ve got much less specific tools and materials.

Let me guess: “eon” and “archeology”, too? “Mediaeval” is acceptable BrE, because superfluous silent vowels are our jam

Media evil

B^)

Hey Jenny

I just returned from a Japan adventure, and while touring the “Imperial Palace”, I marveled at the “Smithy” work on all of the gates and such. It occurred to me that a quality Blacksmith in those days, would be worth his weight in gold.

Oh, look a squirrel..

I lived in Japan for nearly 3 years, in Kobe, and Sapporo, studying Japanese language and art, and teaching. Kyoto and Nara have some amazing ironwork, indeed.

Hello, interesting article! I love reading about daily life in the middle ages. You wrote that “the first nail-making machinery appeared in the 17th century.”, meaning the 1600’s? I’m confused at this because it seems very industrialised for the period, I thought those kind of processes didn’t appear before the mid-1700’s.

How did people back then remove a nail they had nailed in already?

On the James River in Virginia the Indians burnt down everything to erase the English

Later homes were burned, and the nails were gathered for reuse in new buildings.

The most beautiful were the door nails with a large, hammered head the nicest one I ever saw was at the site of Mt Malady Guesthouse/Hospital built in 1611. Some of the spikes/large nails were so corroded up to a half inch thick wide that area still exists but has been placed a mile away. This was also built in 1611. It is the church land where Pocahontas was converted to the Christian Faith and where John Rolfe was assigned as one of the six men to work and garden. It still exists on Garden Creek/Coxendale Creek. Only protected by Mother Nature and Father time.