Asking machines to make music by themselves is kind of a strange notion. They’re machines, after all. They don’t feel happy or hurt, and as far as we know, they don’t long for the affections of other machines. Humans like to think of music as being a strictly human thing, a passionate undertaking so nuanced and emotion-based that a machine could never begin to understand the feeling that goes into the process of making music, or even the simple enjoyment of it.

The idea of humans and machines having a jam session together is even stranger. But oddly enough, the principles of the jam session may be exactly what machines need to begin to understand musical expression. As Sara Adkins explains in her enlightening 2019 Hackaday Superconference talk, Creating with the Machine, humans and machines have a lot to learn from each other.

The idea of humans and machines having a jam session together is even stranger. But oddly enough, the principles of the jam session may be exactly what machines need to begin to understand musical expression. As Sara Adkins explains in her enlightening 2019 Hackaday Superconference talk, Creating with the Machine, humans and machines have a lot to learn from each other.

To a human musician, a machine’s speed and accuracy are enviable. So is its ability to make instant transitions between notes and chords. Humans are slow to learn these transitions and have to practice going back and forth repeatedly to build muscle memory. If the machine were capable, it would likely envy the human in terms of passionate performance and musical expression.

The jam session is an ideal venue for two (or more) humans to play around in the same musical sandbox. Once they agree on a key, the door to improvisation is unlocked. They can play back and forth, riffing on each other’s ideas. Machines may not feel, but they can definitely learn aspects of musical composition by algorithmically interpreting the musical data from a performer and regurgitating it back through different methods. Sara’s talk takes us through a few of the ways that humans and machines can jam out together.

The Jamming Algorithm

Sara wrote a series of compositions that are meant to be played by humans and machines together through interactive algorithms. She starts with a composition called “Breathe” that uses a rule-based algorithm to interpret solo electric guitar input and feed it through a granular synthesizer. The guitar player uses a foot pedal to take FFT snapshots of their performance, which gives the machine information about the pitch and duration of the notes they played.

Once the algorithm determines the prevailing harmonics, it plays them back as ethereal, droning sine waves that sound like an ocean. The algorithm also takes input from a lapel mic taped under the player’s nose to create an amplitude envelope that affects the rate of granular synthesis. This adds a nice staccato counterpoint to the lapping sine waves.

Bach Has Entered the Session

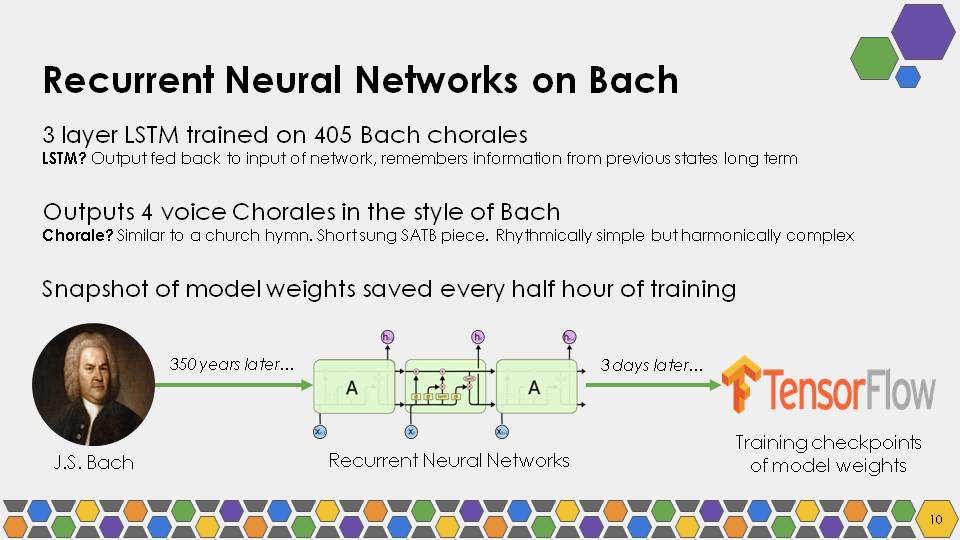

For another composition using recurrent neural networks, Sara used TensorFlow to train a 3-layer long short-term memory (LSTM) on a diet of 405 Bach chorales. A chorale is a short hymn-like piece that’s usually written for four-voice harmony — a soprano, an alto, a tenor, and a bass. The algorithm for this piece is a two-part process. Once the content is there and the network has been trained, the performer uses a MIDI interface to control movement through the neural network checkpoints, sustain or skip selected notes, and adjust the tempo. Sara trained the neural network for three days, and the difference between day one and day two is amazing.

The last composition Sara shares in her talk is called Machine Cycle, which she composed for an ensemble with a MIDI keyboard soloist, a guitarist, and some harmonic sine wave drones. As the keyboardist plays, the machine snatches phrases at random and creates a Markov chain of possible embellishments like grace notes and slight changes in rhythm, before the algorithm plays back the result. While this is happening, another human acting as conductor can control parameters like the output tempo, and whether any notes are skipped.

The idea of humans and machines jamming together is an interesting one for sure. We’d like to feed the sounds of industrial machinery into these algorithms just to see what kind of new metal comes back.

this is great. like Eno’s “discreet music” but on steroids.