The Raspberry Pi was initially developed as an educational tool. With its bargain price and digital IO, it quickly became a hacker favorite. It also packed just enough power to serve as a compact emulation platform for anyone savvy enough to load up a few ROMs on an SD card.

Video game titans haven’t turned a blind eye to this, realising there’s still a market for classic titles. Combine that with the Internet’s love of anything small and cute, and the market was primed for the release of tiny retro consoles.

Often selling out quickly upon release, the devices have met with a mixed reception at times due to the quality of the experience and the games included in the box. With so many people turning the Pi into a retrogaming machine, these mini-consoles purpose built for the same should have been immediately loved by hardware hackers, right? So what happened?

Emulation Über Alles

The first salvo fired in the marketplace was the NES Classic Edition, launched in late 2016. It quickly took the market by storm, selling 2.3 million units in its first six months. Shipments sold out almost immediately, with many units being scalped on eBay for multiples of the sticker price, with varying levels of success.

The device showed that there was a huge market for classic console re-releases at a low price. This was achieved through the use of emulation, rather than recreating the NES’s bespoke hardware or using something like a Nintendo On A Chip. The heart of the system was a quadcore Allwinner R16 ARM Cortex-A7, kitted out with 256MB of RAM and 512MB of flash storage. This was more than enough grunt to emulate classic NES titles, with ample space for plenty of games, too. Besides people just playing the emulated games there was no shortage of people hacking on the NES Classic to see what made it tick.

The formula was so successful, Nintendo boxed up the same hardware in a new shell and launched the Super NES Classic Edition a year later. Other manufacturers rushed in to deliver similar machines for their own back catalogues. Sega delivered the Genesis Mini, and Konami dropped the TurboGrafx 16 Mini, both based on the ZUIKI Z7213, with similar specs to the Nintendo units. Sony’s Playstation Classic upped the ante, somewhat, needing more power and storage to deal with 3D games from the CD-ROM era. It packed a full 16GB of storage and 1GB of RAM, running a Mediatek MT8167A. Later on, there were further spins on the same concept, like TheC64Mini and even the NeoGeo Mini which shipped in a tiny arcade cabinet, complete with a 3.5″ LCD screen.

Capabilities

It wasn’t long before enterprising hackers cracked the machines; guides to add more games to the NES Mini were online within months of the NES Mini’s release. Similar hacks are available for most, if not all, the systems that have been released this far. Some, like TheC64 Mini, even officially welcome users to add more software which really should have been the standard for all these reissued systems.

However, there’s more on the table than just running a different set of ROMs. Packing ARM processors, flash storage, and HDMI outputs, they have the makings of a small single-board computer. While some have limited interfaces, many pack in USB ports too, making hooking up peripherals theoretically easy. Ten years ago, these would have been tantalizing machines for hackers to open up for all manner of projects. However, in a world with Raspberry Pis on the shelf for under $50, it’s difficult to justify the effort required to turn these machines into more fully-fledged platforms.

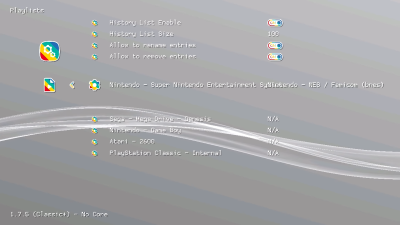

Efforts thus far have focused almost entirely on gaming. Not content to load more titles from the systems in question, hackers have ported the RetroArch emulator to these micro consoles. This enables the ARM systems to emulate a wide variety of systems, from the dawn of the home console era all the way up to modern consoles like the Gamecube and Wii, for systems with the power to do so.

Getting Retroarch going is achieved using a tool by the name of Hakchi on the NES and SNES mini, ironically the SNES Classic emulated Playstation games better than the PS Classic in some cases. Due to the lack of USB ports, Wii Classic Controllers are the only viable choice for those seeking proper analog sticks for use with their Nintendo Mini consoles.

In the case of the Playstation Classic, running Retroarch is achieved with BleemSync, named for the original Playstation emulator, or the later Project Eris. Reportedly, it too runs better than Sony’s in-house emulator, which may partially be due to the decision to include PAL ports on the stock machine.

Conclusion

For those wanting an emulation system in a funsize package, the Nintendo and Sony offerings may be attractive. The fuss of using hacked tools and limitations on controllers may prove too fussy for most however, when the alternative is simply slapping a Raspberry Pi in a nice plastic replica case instead. While the systems have largely been cracked wide open by hackers, there’s little thirst to get a full desktop OS or other code running on the platforms. Single-board computers are cheap and plentiful, so there’s little incentive to bother with one that has even the lightest of restrictions standing in the way.

It’s a very different scene to the era in which this website was born. In the early 2000’s, torrents reigned supreme, and there were few devices suitable for playing digital video content on television screens. The Xbox was a prime target, featuring USB, ethernet, and an x86 chip all in a TV-friendly package. The Xbox Media Centre project (still around today but rebranded as KODI) and even full Linux distros quickly sprung out of the woodwork, gracing the loungeroom of hackers around the world. Being able to do something no off-the-shelf product readily could, huge amounts of time were poured into developing on the platform.

In the case of these micro consoles, there’s very little they can do that can’t be done better with other hardware. Even their primary role of playing retro games is arguably better experienced on the Raspberry Pi, even for the technologically inexperienced. Ultimately, what manufacturers sold was nostalgia in a cute plastic box, and I imagine that this is a fad that won’t last much longer. As always, time will tell.

“For those wanting an emulation system in a funsize package, the Nintendo and Sony offerings may be attractive.”

Or, y’know, legal access to the actual games. Silly stuff like that. Especially with the SNES Classic there are several games on there that if you wanted to obtain legal access to them it’d cost way more than the cost of the SNES Classic itself.

Well to be honest, I doubt many care about the copyright issues. Even Nintendo doesn’t have the might to squash the ROM sharing culture.

It’s weirdly intermittent. Like, they’ll go on a tirade for a few years shutting people down and in some cases really inflicting financial harm on people, and then be quiet for a long while.

Actually *having* the games for personal use is obviously not a target for them, but if I were someone who, for instance, was a developer on an emulation setup or had a super-popular project or, I dunno, sold setups to people (or some other commercial activity), I personally would want to have all *my* ducks in a row just in case a $40 billion dollar company decides to come after me.

Perhaps, perhaps not, but they are very active on that front and a lot of the retro scene try to steer clear of Nintendo stuff now.

I mainly want to play games that I used to play as a kid. I already bought the games when they were new. And in some cases I bought them again on the Wii store. I am legally entitled to run a few hundreds games in emulation at least for personal use.

“I mainly want to play games that I used to play as a kid. I already bought the games when they were new. ”

Yes, that’s my point. Some of the games on the SNES Classic, for instance, are stupidly expensive to get. Super Mario RPG is nearly $60-70 alone, and with the Virtual Console going away (…presumedly) and it not being on the Switch online thingy, I don’t think there’s another way to legally own it.

“I am legally entitled to run a few hundreds games in emulation at least for personal use.”

Sure, that’s entirely my point. You can pull the ROMs from the VC data on a Wii, or from the actual cartridges themselves. However you can also pull the ROMs from the SNES/NES Classic (or the PlayStation classic or Genesis classic) and that’s a relatively cheap and legal way to obtain some of those games.

I can download the ROMs from the internet, legally.

The whimsical attitude towards software piracy here on Hackaday is worrying.

Software piracy is a net good for everyone involved.

Because…it’s interfering with the returns on your ms and pharmaceutical stocks?

Or he could be someone whose livelihood has been harmed by software piracy.

The problem is that software piracy’s a broad term, because of the idiot copyright system in the US (and most of the world). Someone goes out and broadly pirates a brand new video game that a company spent millions on and the copy protection was flawed, and the company goes bankrupt because sales don’t meet expectations. Is that piracy OK? Not to me. I think most people would agree that’s not okay.

Someone goes out and broadly pirates a 40-year old piece of software whose developer no longer exists? I can’t imagine *anyone* would say that’s *not* okay.

The problem’s the middle, and really, it’s because of the idiocy in the current system. Nintendo can hold onto the rights to Super Mario Bros. for forever, and it costs them nothing to do so. So they do. It’s easy to understand their point of view, they *do* still make money on it. The problem is that there’s a *reason* copyright is supposed to expire – because it improves the public good. And so for Nintendo, there’s absolutely no cost/benefit they have to do. Costs them nothing to control it, and they gain money from it.

The frustrating thing is that the fix is easy. Really easy. Make copyright expire on reasonable timescales, but allow it to be extended via a purchasable license, and have the cost of that license escalate over time. Nintendo wants to keep Super Mario Bros. under copyright for 100 years? Fine. But by then it’ll cost $5M/year or something. Make them *think* about keeping it in-house.

This is why software piracy is such a huge problem. Copyright *is* important. It’s the entire key to Free Software, for one thing. You can’t be “okay” with copyright in one case, but not others. But the problem is that the system in the US means that to defend copyright, you suddenly are also defending preventing 40-year old pieces of software from being released and studied, and that’s insane.

But it’s the system we have.

AT games has been making the flashback consoles for darn near a decade but no, Nintendo fired first

Before the Atari Flashback there was the Power Player. Imported to the USA by Theodore Robert Wright III, until the feds started to crack down.

That was the one styled like an N64 controller with a dummy analog stick, a varying amount of hacked and modded NES and Famicom ROMs onboard and usually a Famicom cartridge slot on the bottom that worked on some of them.

This guy’s life could be a series of action movies. At age 9 he tried to sail a tiny boat across Lake Champlain. Not long after 30 he was an international arms dealer, involved with all kinds of schemes and scams, family man, former playboy, extreme adventurer, a pilot who could fly pretty much anything, and much more – and finally in prison. Apparently he never *directly* dealt with people in the illegal drug trade, but he did buy and sell to and from people who sold and bought stuff to and from people in the drug trade.

https://www.texasmonthly.com/articles/it-was-never-enough/

What got the guy on his tail who eventually nabbed him was, for T.R., a penny-ante insurance fraud torching of a private jet.

Those were unlicensed Famicom clone with many games that still had copyright protection. Atari Flashback was the first 100% legal retro console in USA

That was a good read, thanks :-)

Speaking of AT Games.. The Firecore devices had a Mega Drive slot, too and included an emulator for Mega Drive games. In addition, the company released the Passport cartridge to play game image from SD card. Long before the NES Mini..

“The first salvo fired in the marketplace was the NES Classic Edition, launched in late 2016.”

Unless maybe you’re talking about some other miniaturized versions of classic gaming consoles with specific attributes that I missed in the article:

I believe the Atari Flashback (yuck) was released in 2004. The Flashback 2 (actual compatible hardware not an emulator) was released in 2005, according to a Wikipedia article. The FB2 was of interest for “hacking” as it exposed and identified solder points on the board to which an actual, original cartridge could be connected. Numerous successors have since followed in the Atari FB line.

By the standards of this article, maybe the FB2 would be considered a “pre-war” mini classic console. :-)

Note: The first Atari Flashback was not an emulator as may have been implied by the construction of my posting. I’m pretty sure it was a Nintendo-on-a-chip system running ported games.

The original Atari Flashback was a NOAC. The Flashback 2 (and 2+) were essentially an Atari On a A Chip, based on the main chip used in the 2600jr. There were three revisions of the AOAC in the FB2 but they all have issues with some games due to not having some of the opcodes. The fourth (and apparently last) revision used in the 2016 Flashback Portable is supposedly compatible with all the 2600 games except Pitfall 2 and Supercharger games.

When AtGames took over the Flashback series they reverted to using a NOAC.

Never mind. I realized that the article is referring specifically to emulated systems.

Most of these Chinese consoles are NOAC blobs with a flash chip containing the games, nothing else.

https://jmp.no/blog/cool-nes-baby

More “advanced” units have a low-end ARM chip (for example the Allwinner a20 in the C64 mini) and a higher price point along with it. Nothing really to hack, it’s all priced out. A better effort would be to get a higher end ARM SBC (A73 for example) or an old PC and gather up emulators and ROMs.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nIBuTJ2kNb0

So far I have built 47 MAME arcade machines in varying sizes utilizing Raspberry Pi’s and mame4all. I re-purpose old 4:3 LCD monitors from Value Village at 8$ a pop and still have a dozen in storage. :) All cabinets are made of wood and some of it reclaimed from furniture. Some have been sold to pay for more parts but the majority of the machines were donated to multiple charities, family and friends.

In my opinion, thin clients are a highly underrated alternative to raspberry pis. I have an hp t620 — it was $30, it’s small and already has a case, it has a quad core processor, radeon graphics, 4gb of ram, and came with a 16gb m2 sata drive (I have upgraded this to 256gb). It is great for games — In addition to running linux and retroarch, I have xp installed on it (though it can also run windows 10) and am enjoying Doom 3, Morrowind, and Civs3 at the moment. The t620 plus has a pci slot for a different GPU too.

Keep an eye on the Lenovo Tiny series, I’ve got Sandy Bridge to Kaby Lake hexcore systems, and the newer ones have PCIe x8, some of the barebones were ~$30, you can use $10 Core processor and $10 4gb of ram, suddenly the Rpi isn’t such a great console. ( Its still a decent choice for a portable). M73 M92 m720q p320 p330 encompassparts is where I got all the stuff to convert my m720q into a wannabe second p330, like pcie riser, rear panel and side panel with GPU vent.

Also ran are the chromebox series with upgradeable bios (coreboot, windows, linux) ram (some even have 2 slots) and m.2 SATA

My question is where did these companies get their emulators from? Were they written from scratch, or did they pick up the open source emulators that they otherwise seem to hate so much? Maybe with a little tweaking and re-skinning to hide their work.

I saw an article about this somewhere, and yes they used reskinned open source emulators. Link? Let me look.

Oops, let me walk that back a bit. Sony used an open source emulator, Nintendo used their own on top of Linux.

https://techcrunch.com/2018/11/09/sonys-playstation-classic-uses-an-open-source-emulator-to-play-its-games/

The Nintendo ones as far as I know are bespoke: pretty sure someone would’ve figured out if they were based on something. Sega contracted out to M2 for the Genesis Mini, so presumedly theirs is in house (well, in M2’s house).

The PS Classic flat out uses PCSx, with fairly stupid settings, so it’s embarrassingly bad.

The Nimtendo ones have some performance metrics (input lag, for example) that they’re nearly unparalleled at, so they obviously did a fair amount of work totally by themselves.

Nintendo develops its own emulators. The chinese clones are probably just packing open source stuff.

I doubt they hate the emulators themselves, except that they encourage copyright infringement.

Does anyone else notice the timing is “off” on everything except the original consoles?