For a lot of us, there’s a bright line separating the books we enjoyed as children from the “real” books of our more mature years. We all eventually age out of the thin, brightly illustrated picture books we enjoyed in our youth, replacing them with thicker, wordier volumes with fewer and fewer illustrations, until they become so dense with information that footnotes and appendices are needed to convey all the information, and a well-written index is a vital necessity to make use of any of it.

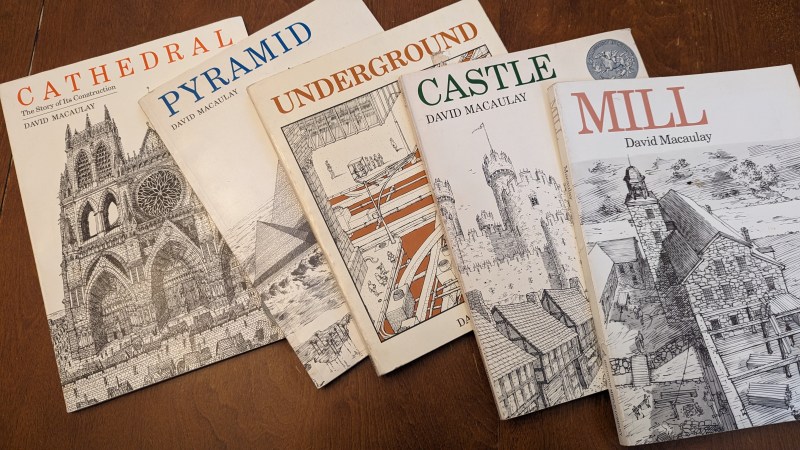

Such books seem like a lot less fun than kids’ books, and they probably are, but most of us adjust to the change and accept the fact that the children’s section of the library doesn’t hold much that’ll interest us anymore. But not all the books that get a “JUV” label on their spines are created equal. Some are far more than picture books, even if the pictures are the main attraction. The books of British-born American author David Macaulay come to mind, particularly the books comprising his Architecture Series.

Macaulay’s books were enormously influential in developing my engineering sensibilities, and are still a pleasure to thumb through these many years later. I still learn something about the history of construction and engineering when I pull one of these books off the shelf, which makes them Books You Should Read.

The View From Below

I first discovered David Macaulay at an age when I was perhaps already pushing things a bit to be browsing the children’s section. I remember clearly happening upon a thin volume with a simple, single-word title: Underground. On the cover was a pen-and-ink drawing showing what a city might look like if you had X-ray vision, which was an instant hook for me. Even at that age I had an abiding if slightly weird interest in infrastructure, and seeing how electrical vaults, sewer pipes, and subway tunnels lace the parts of a city together under its streets was pretty powerful stuff. The rest of the book was just as fascinating as the cover, with intricately detailed drawings of everything lying beneath a typical city.

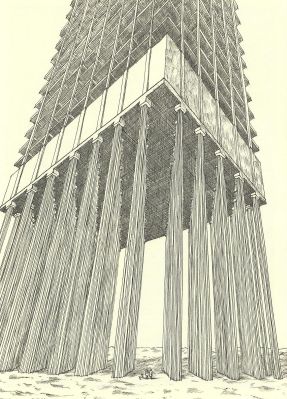

Aside from being a fabulous introduction to the engineering principles used to create the built environment — what Underground taught me about the different types of foundations used to support skyscrapers sticks with me to this day — I think the fact that Macaulay is somehow able to create otherwise impossible points of view to convey these principles is one of the most valuable parts of the book. There’s one illustration in Underground that shows a building from below, looking up into the forest of pilings from the bedrock upon which they sit, with the soil magically subtracted from the scene. The imagination and skill needed to visualize a scene like that and capture it on paper tells you all you need to know about Macaulay’s books.

Luckily for me, Underground was far from a one-off. In fact, by the time it was published in 1976, Macaulay had already published three books in what would eventually become his eight-volume Architecture Series. His first book, 1973’s Cathedral, set the tone for what was to follow: books focusing mostly on historical construction methods and materials, in fictional but period-correct settings, using intricately detailed pen-and-ink drawings to show how such buildings were constructed.

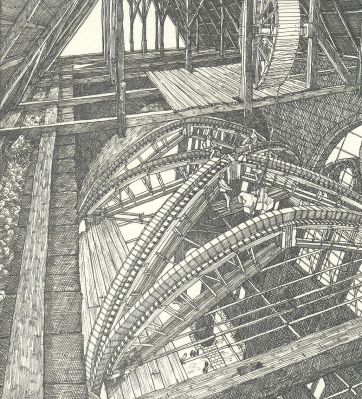

Cathedral follows the fictional French Gothic-style cathedral of Chutreaux over a period of 86 years, from its planning to the final consecration. The drawings are wonderful, with enough detail to satisfy the curiosity of older kids and adults while still telling enough of a story that younger children will be entertained. And there are Easter eggs galore — the section on building the groined vaults over the church’s choir shows a tiny bird’s nest being built atop the wall, with the baby birds eventually flying away as the ceiling is completed. Finding a treasure like that as a kid was fascinating; reading the book to my kids many years later and having them find it was poignant.

Drawing On The Impossible

Cathedral uses a lot of traditional drafting views — plans, elevations, cross-sections — to illustrate exactly how a Gothic cathedral actually stood up. Even as a youngster, I was able to see how flying buttresses worked, tracing the path of the forces from the roof trusses to the foundation through his excellent drawings. Later books of the series, like 1977’s Castle, which traces the construction of a hypothetic 13th-century castle in Wales, continued this tradition, with section drawings detailed enough to show how fireplace chimneys were built, and exactly how a castle’s many garderobes were connected to cesspits — or directly to the great outdoors. Plenty of entertainment in those illustrations, too — nothing hooks a kid better than potty humor.

All of the early books of the Architecture Series — Cathedral, Castle, and 1974’s City, which covered the construction of an imaginary Roman city, make effective use of what I’d later discover in Underground — the impossible point of view. Many of the drawings in these books show what construction would look like if a drone were hovering overhead taking pictures. Castle has a fantastic picture of the inner curtain wall and a defensive tower being built, looking down almost vertically into the structure. It shows the thick walls with cut stone faces and rubble infill, a growing spiral staircase, and the interior of the growing castle.

Illustrations like these add so much to the reader’s understanding of how buildings like these worked, and his “long shots”, where he gives overviews of the entire project, really help you appreciate the scale of the work. Castle, where the fictitious walled town of Aberwyvern springs up around the castle, has many good examples of this, with a series of pictures showing the growing settlement as you might see it from an airplane. The progression of pictures shows at first a few buildings inside the walls, centered around the town well, eventually growing outward as more half-timber, wattle-and-daub houses are added until the whole town fills the walled area and spills out into the surrounding countryside.

Other works from the Architecture Series include 1975’s Pyramid, which covered ancient Egyptian construction, and the slightly oddball Unbuilding, a 1980 book that nicely shows off Macaulay’s quirky sense of humor. The backstory for the book involves a rich Arab prince buying the Empire State Building and then having it disassembled for shipment back to his kingdom for reassembly. He uses that as a springboard to discuss how the iconic skyscraper was originally constructed, just in the reverse order. It’s a fascinating book, but unlike the earlier books, it’s one I’ve only read once; not many libraries I frequented seemed to own it.

The two last additions to the series are 1983’s Mill, which shows the establishment of a water mill in New England and the fictional mill town that grows up around it, and Mosque, which Macaulay wrote in 2003 in response to the 9/11 attacks. Mill is particularly interesting to me, partly because I grew up in New England but also because water-powered mills are historically and technically fascinating to me; some of the illustrations in the book are so detailed that you could almost use them to make blueprints for building a waterwheel and the surrounding machinery.

Kid’s Books, But So Much More

At the end of the day, it’s hard to argue that David Macaulay’s Architecture Series books aren’t children’s books. There’s plenty of text, and while the language is deliberately simple — but never dumbed down — it’s really the illustrations that are the star of the show. But these books are so much more than “just” children’s books. With a few — OK, many, MANY — strokes of his pen, Macaulay is able to show complex engineering ideas that a page of text would struggle to explain, and bring life to long-obsolete construction techniques. Anyone interested in the confluence of history and engineering will find these books endlessly fascinating, no matter how old they are.

So maybe these aren’t children’s books so much as they’re imagination books. And no matter where you are in your engineering journey takes you, everyone can use a little imagination.

The way things work is also a fun book.

Engineering in plain sight by Grady Hillhouse would appeal to readers of underground (has a YouTube channel).

https://www.amazon.com/Engineering-Plain-Sight-Illustrated-Constructed/dp/171850232X/

First thing that came to my mind. I LOVED that book as a kid. Hours of enjoyment! I still have it, too

The Way Things Work was my bible as a kid, but somehow these all passed me by.

Never came across these books… but now I may have to. Thanks Dan!

I grew up with these, a gift from an uncle in architecture. Timeless works of art and educational.

There’s also The Way We Work, a gorgeous anatomy book, and The Motel of Mystereries, a fictional, future archeological dig of a 1980s era motel, in which the archeologists make wildly incorrect assumptions about the function of the building and its contents.

Macaulay’s “Unbuilding” is one of my favorites. It details the structure of the Empire State Building from a unique standpoint: its disassembly to ship to the Arabian Desert after its purchase by a wealthy oil magnate. It has all his signature art, plus a novel take on how to describe the structures and systems of a skyscraper.

I wonder if such books are also available in German, my kids do not speak English, yet.

Ohh, they are available in German !

I just checked – I have Mammut-Buch der Technik (Mammoth book of technology). Had it as a kid and I totally dig it. It’s set in the stone age (with Mammoths and stuff) but covers everything up to the computer (and the mouse). And nuclear reactors. And simple things like parking meters and how colors work.

It’s got tons of drawings that are like massively enlarged (with people running through – that computer mouse would be the size of an airplane hangar)

“The Way Things Work” is the English title, and they released an updated version a few years ago. Still as charming as I remember it as a kid.

Found the German

I have the Dutch translated version of a couple of his books:

“De Stad” (City – A Story of Roman Planing and Construction)

“Het kasteel” (Castle)

“De Kathedraal” (Cathedral – The Story of Its Construction)

“Ondergronds” (Underground)

“De Piramide” (Pyramid)

And I have a highly similar book by Silvie Vieillevigne

“Parijs” (Promenade dans Paris)

If you’re near Delft, the Netherlands and want to borrow them; you’re welcome. Contact me at info @ buttonius dot com

Add ‘Great Moments in Architecture’ to the list. It’s pure fun.. a section view of the Sistine Chapel with drop-hung celing, Notre Dame with vinyl siding, etc.

Also “Motel of the Mysteries”.. an archeological dig into a mid-20th century motel buried by a sudden drop in postage rates for junk mail. The depictions of the ‘ceremonial headdress’ found on the porcelain throne in the antechamber are worth the price by themselves.

Oh yeah. I remember that one. It is hilarious. The religious interpretation of all the common things. Brilliant

I believe Reader’s Digest had an abridgement of that story.

Motel of Mysteries is a great book to teach critical thinking.

When I was at the Minoan Palace on Crete, the guide gave the monolog about the palace, frescoes, royal chair, ceremonies, blah, blah, blah…

I couldn’t help but ask, “Did they find any writings that say all this or

is it speculation from the archaeologists?”

The guide excitedly explained they found storehouse records in Linear-B and another tourist explained Linear-B was a predecessor of Greek (He was a professor from the US.)

Sigh – I wonder if 1000 years from now, archaeologists will dig up Picasso paintings and conclude women in our time had 3 eyes on each side of their heads.

John Markus wrote another series of books that should be essential reading for any avid hackers. Each is a compilation with *thousands* of electronic circuits, complete with schematics, part values, a quick description, and references to the original article (archived from various electronics magazines, books, and manufacturer’s application notes). Each volume covers a particular time frame; the early ones cover vacuum tube and relay circuits, later ones use transistors, then ICs, then micros. I have four; Sourcebook of Electronic Circuits (1968), Electronic Circuits Manual (1971), Guidebook of Electronic Circuits (1974), and Modern Electronic Circuits Reference Manual (1980). If you want to learn *every* way anyone has built any particular circuit function, here it is!

No joke, being given The Way Things Work as a kid is why I’m an engineer today. That book (and the “New” way things work(ed in the 90s)) are true masterpieces. I have several other of his books, but wasn’t aware of all of these. Gonna try to find them ASAP!

Brings back fond memories. I was a big fan of Castle. The drawings were superb.

I love illustrations like this. The one on the Cathedral… can’t stop looking. What is the technique called? Is it lithography?

I think they’re all just pen-and-ink drawings. Damn nice ones, though.

You should make Tik-Tok videos about it !

I believe it is “spline”, not spine.

I read these in Skool many many years ago as each was released, I would buy the next one.

The woman I called wife at the time threw them away during an organizational orgy in 1996, attempting to de-clutter my existence.

She was very successful, she decluttered herself right out of my life.

Sadly too late for my David Macaulay books, National Geographic Atlas, Oxford English Dictionary, Journels of Howard Carter, as well as a majority of my National Geographic “coffee table books”

Annulment was too good for her, lolz.

I recall a talk of David Macaulay at the famous ATG night on one of Apple’s developer conferences held in San Jose. One fun thing was he had a tie and it was cut off so he became one of the guys amids about 1000 programmers. I remember it well as he showed the perspective from NY from under the ground.

David Macaulay has written on more than architecture and technology. One of his other books is “Baaa!” where humans suddenly vanish, providing sheep with the opportunity to build a civilization upon the remains of what humans left behind.

Upon seeing the title of this thread, how many other people clicked on it thinking they were going to learn about a book covering CPU architectures?

To be honest, I thought it might cover software architecture too