If you grow up around a working blacksmith’s forge, there are a few subjects related to metalwork on which you’ll occasionally have a heated discussion. Probably the best known is the topic of wrought iron, a subject I’ve covered here in the past, and which comes from the name of a particular material being confused with a catch-all term of all blacksmith-made items. I’ve come to realise over recent years that there may be another term in general use which is a little jarring to metalwork pedants, so-called Damascus steel. Why the Syrian capital should pop up in this way is a fascinating story of medieval metalworking, which can easily consume many days of research.

Damascus? Where’s That?

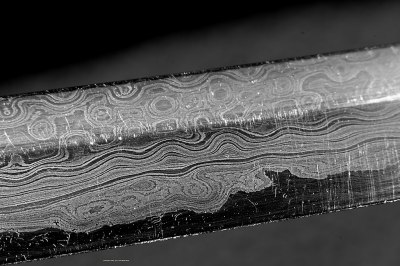

The Damascus steel you’ll see in YouTube videos, TV shows, and elsewhere is a steel with complex bands and striations on its surface. It’s often used in knife blades, and it will usually have been chemically treated to enhance the appearance of the patterns. It’s a laminate material made by pattern welding layers of different steels together, and it will usually have been worked and folded many times to produce a huge number of very thin layers of those steels. Sometimes it’s not made from sheets or ingots of steel but from manufactured steel products such as chains, in an attempt to produce a result with more unusual patterns.

The point of making such a laminate goes beyond the patterns; like any such laminate the idea is to combine the properties of the different materials used. In this case an ideal knife must be hard enough to take a sharp edge yet also flexible and not brittle such that it does not crack or shatter when subject to stress, something the constituents of the laminate should be selected to deliver. In this way the smith is trying to replicate something like the laminates seen in a Japanese Katana sword, where thin layers of steel are formed on the surface of the iron in the smith’s charcoal-fired hearth, which become alternating layers of steel and iron in a similar folding process.

Making these Damascus steels is a highly-skilled craft, and as you might expect a knife made this way is likely to be expensive, and pretty good at holding an edge, if that’s what you’re after in a knife. But are they really Damascus steel? Like the whole wrought iron question, there’s something to get smiths talking.

Will The Real Damascus Steel Please Stand Up?

The phrase “Damascus steel” comes to us from medieval-period swords manufactured in the Middle East, and known at least to Western Europeans through their sale in Damascus. These swords share the surface patterning with the modern blades described above, and were legendary for the properties of the metal.

But their manufacture wasn’t the same pattern-welded laminate, and neither did their steel come from Damascus itself. Instead they were made from ingots imported into the Arab world and made by ironmasters in modern-day southern India and Sri Lanka. The steel from those regions was so-called crucible steel, in which the steelmaking process takes place in a sealed crucible in the liquid phase rather than in the solid or semi-solid phase as in for example on the surface of the Japanese Katana steel. The particular impurities found in the ores from these regions gave rise to a very high-carbon steel with significant quantities of carbide inclusions, and it was these which lent the finished product its patterned appearance.

The Point Is In The Forge Work

So if the original Damascus steel is derived from a particular medieval steelmaking process from a specific region and the modern Damascus steel is a pattern-welded laminate of different steels, which is the real Damascus steel? As a language purist I’d err towards the original, but that’s not to dismiss the value of the modern pretender. It’s worth getting hot under the collar about the use of the phrase “wrought iron” because the real thing is something special while the fakes are often mass-produced rubbish, but that’s not the case with Damascus steel.

The modern Damascus steel knife may never have been near Damascus and certainly won’t be made from Indian or Sri Lankan crucible steel, but just like the blade you’d have bought in medieval Damascus, it represents the skill and work of a blacksmith at the peak of their craft. Pattern welding steel to make a laminate is hard, I’ve tried it and I can tell you it’s not for the dilletante smith. Anyone who can do that to a high standard is worth paying very good money indeed for their work.

Header image: “Damascus steel hunting knife” by Rich Bowen

And it is well known that the more layers the better, until they are invisible, what I will start selling as “homeopathic damascus”.

I will contend that properly chosen and treated mono-steel will outperform a pattern-welded steel in all respects other than looking pretty. And “damascus” blades certaily do look pretty.

This very old video shows the making of pattern-welded rifle barrels. At one point there is a barrel with the owners name pattern-welded into the steel itself. That’s impressive craftsmanship.

But I don’t think that any modern shooters consider such barrels _superior_ to a modern one.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fa9dlvRDuQU

You have to know at what task they are to ‘outperform’ to make that claim – an optimal high quality modern steel grade for the job in hand will usually be better than the laminate I’d suggest, being very uniform and predictable but still not always. What it will almost certainly always be is massively cheaper to make.

And blades are probably a good case in point where its possible a laminate can outperform a monosteel, as there are so many types of blade getting put through so many different use cases – in many cases you probably can get a suitable mono-steel and/or adjust the cutting geometry for the job, but selectively putting different grades in places you need them should be better or allow for better geometry, and even a generic pattern weld with no particular effort to place the best grade in the best place may well outperform a mono-steel depending on what parameters are the most important for that user.

That’s an important concept – laminate was done because *it was the best they could do* with their technology.

We can do better materials and laminating rarely adds anything today

You’re correct, at least if you’re comparing blades made with a very good powder metallurgy steel (such as CPM magnacut) against even well-made typical modern damascus, which is generally using layered and folded steels chosen to produce contrasting light and dark swirls after etching rather than for the best material properties. That being said, there are blades which are made with a smaller number of layers of excellent steels which can outperform a single layer of any of their constituents, and it’s entirely reasonable to think that if you could choose the nanoscopic structure to be whatever you want, then it wouldn’t be homogenous. For an example of beneficial layering, you can put a very hard but somewhat brittle steel in a sandwich between two reinforcing layers of a different steel. The hard steel forms the edge, and the other two keep it strong. The visual effect is not prioritized, nor is there any desire to average out the two steels by folding a thousand times or any such thing.

I was under the general impression that the “folded a thousand times” thing was beneficial in that it’s approaching a homogenous combination of two component steels, though I could easily be mistaken. The other damascus that’s actually a description of patterned crucible steel was historically a fairly good way to get a good result, since they couldn’t get a precise mix of pure elements or a perfect heat treat procedure. It doesn’t fall completely apart and has nice hard parts to use. And if you see the patterns, you know the structures formed. Mind you, I’ve no experience with the stuff, but at least it’s an interesting effect and isn’t the same as just layering random metals.

“For an example of beneficial layering, you can put a very hard but somewhat brittle steel in a sandwich between two reinforcing layers of a different steel.”

Morakniv does exactly that in their Laminated Carbon blades:

https://morakniv.se/en/knife-knowledge/the-blade/

“Laminated carbon steel (LC)

This steel grade is unique for knives from Morakniv. The core of the blade is made of high carbon steel surrounded by a softer alloyed steel layer”

I’ve always wondered about this: As far as I can tell, they can’t really predict or control which of the starting materials ends up at the very edge of the blade; it may be the harder and more brittle steel, or the softer steel, and probably isn’t even the same along the length of the blade, making some parts more suitable to hold an edge than others.

Am I missing something here?

A gun barrel is kind of a specific case. It’s a pressure vessel. I have a couple antiques in which the barrel was made by welding or brazing wire or ribbons of steel wound around a mandrel, which is not something to take your chances with these days. Making a pressure-holding component by boring or milling out a solid piece of metal is much wiser.

Otherwise you risk becoming victim to the old gag where Bugs Bunny puts his carrot in the end of Elmer Fudd’s shotgun and it all peels outward like a banana.

Great article, probably not a topic many people know about. I have also read that the unique steel used in original Damascus steel, called wootz also contained carbon nanotubes.

Japanese blades were layer forged, the resulting pattern is called the hada. They were differentially tempered, producing the hamon pattern.

Modern Damascus is beautiful, I own a number of blades. But modern crucible steels have superior properties.

I read that the nanotube idea had an alternate explanation available – something about carbon spheres enclosed in softer material being split open after being deformed into pancakes or tubes. The alternative theory says that there’s not really tubes everywhere, just hollow carbon bubbles that only look like tubes once it’s been worked and etched and they’re left behind from dissolving soft iron.

I couldn’t say I know for sure but the structure is neat for what it is.

Ah, the meme molecule.

“Making these Damascus steels is a highly-skilled craft, and as you might expect a knife made this way is likely to be expensive, and pretty good at holding an edge,”

I really don’t expect that, to be honest. There are knives that do that, but it’s far from all. You can get dirty cheap Chinese made knives with “damascus” steel that won’t even sharpen properly. I know, because I have some because I liked the pattern and used it to make my own knife.

Just because it’s laminated steel, doesn’t mean anything.

“Sometimes it’s not made from sheets or ingots of steel but from manufactured steel products such as chains, in an attempt to produce a result with more unusual patterns.”

That is indeed the problem. Using chains or other old products don’t give you the result you want in a good quality knife. You need to start with quality steel to get a quality knife, unless you use a San Mai method, where you put the damascus on the outside with a layer of quality knife steel in between. That’s commonly used. It’s easier to produce and the steel at the center is hardened properly. The damascus in that case, is only used as a “pretty” layer.

Have to admit, making damascus steel can be quite a pain. Was working on stainless steel damascus as a try and the temperature difference between too cold and it’s burning up was too close. Might need different stainless to try it next time. Carbon steel is, in my opinion, quite a bit easier. I prefer 1.2003 (75Cr1, comparable to O2) as a center steel for San Mai at the moment. Easy to work with.

San Mai: The outer layers do at least reinforce the central layer, which otherwise couldn’t safely be as thin and hard. According to the people who do it, it’s still helpful not to choose purely for aesthetics with the outer layers too.

In theory, yes. But it’s often done for the looks. Most people don’t really care about damascus besides the “cool factor”. When it’s done on an actual battle ready katana or something then I get it. But for a camp knife or something, it’s really not that interesting. Then it’s about the part that cuts that needs to stay sharp and the looks of it.

Oh, sure, it’s usually not. Replace “do reinforce” with “can reinforce” if you like. But the use of san mai that I liked was on a ka-bar and I was impressed by the strength-and-sharpness vs weight. So I don’t think it needs to be only for a… “enthusiast”‘s sword rather than being legitimately specified for performance reasons.

You can also find “Damascus” blades that are just plain ‘ol steel, with a Damascene pattern etched or printed on the surface. No resemblance, property-wise, to actual Damascus steel, of course.

Do you do cannister damascus? The plain steel box keeps oxygen away until the different metals are forged together. This guy in Ukraine has made knife blades that way from a wide variety of steel items + some kind of steel powder to fill up all the space in the box. https://www.youtube.com/@shurap

What’s neat is how often despite all the squeezing, cutting of ingots, welding the pieces together, squeezing again, sometimes several times, the shapes of the original items are still recognizable though distorted.

He also makes blades with other methods. His forge, power hammer and other equipment he built.

That’s not steel powder he uses. That is flux, probably borax:

https://makeitfrommetal.com/forge-welding-flux-or-no-flux/

He puts a very fine, grey powder into the box along with whatever steel items he’s forging. Flux is sprinkled onto the outside when he’s forging pieces of the ingot together.

I’ve watched some of the videos.

The powder that goes in the box is still flux. It is needed to help all the little pieces in the box join to one piece during forging.

No, I weld layers together, then forge them. And that’s usually a flux they add (if it’s white). Some add carbon steel powder but that’s rare. I know the channel, he’s a joker. Makes cool stuff, but adds things like pepper and stuff to his package. Makes me laugh. I don’t have a power hammer. I wish I did but that’s not possible right now. I use an anvil and my arms and usually get help from friends willing to bang hammers for a while. Making a box around it does work but usually when you use things like scraps or tiny materials you wish to contain. The problem is that it can become more difficult to grind away the box after forging it. But if you wish to use ball bearings, nails, broken blade pieces etc, then yeah that’s the way to go.

On yt you can find great channel from shurap. He makes knifes out of all sorts of steel, and effects (I mean visual appearance) is fantastic.

Look for shurap and Damascus steel.

It’s only Damascus steel if it’s from the region of Damascus. Otherwise it’s just sparkly steel.

Making “damascus” blades is seen frequently on “Forged in Fire” on History Channel.

I’m afraid I have issues with that show. Too many people watch it and see the techniques used there by bladesmiths, and confuse them with techniques used by all blacksmiths rather than just that particular speciality. As an example I had someone tell me I should quench in oil rather than water, because someone on that show did it. Nope, every smith I have ever known uses water.

Ha, it’s the blacksmith version of a doctor with a patient who spends too much time on WebMD

Compared to the other things that shows often get wrong, isn’t it a blessing if the worst issue that springs to mind in a bladesmithing show is that the audience may not get a complete picture of other kinds of smithing?

I haven’t watched it a lot, but I heard that people who appeared on it felt like it was fairly real for something that has to be a profitable show. So sure, they have to race to make a knife out of oddball materials, and they’re overly enthusiastic about certain things, but at least they weren’t faking everything. *cough* topgear *cough*

My issue is that they seem to get morons on the regular. Guy goes to the final round because the third forgot to quench or didn’t follow instructions. Then we see his home ‘shop’ is two pieces of OSB over a tire fire and he has to make Excalibur.

The arrogant ones annoy me, but not the ones who just don’t have a lot of equipment – as long as they know what they’re doing.

Machinist by day, blacksmith on side for about 7 years.

I use water myself to quench at the smithy, but to be clear- there are actually 3 classes of hardening steel types- water, oil, and air. W2 is often drill rod stock in the USA,and is a water hardening tool steel. O-1 is a very common toolsteel that is oil hardening. H13 is an example of an air hardening tool steel, often used in hot punches and dies used in forging other metals.

To be clear- its that certain steels are meant to be quenched in one of those ways to force correct heat transfer rate to allow full hardening conditions to occur. Water and oil hardening steels, ime, can be hardened with either to a degree, but you won’t get the full hardness condition perhaps. Air hardening toolsteels really are typically unforgiving, and require a set cooldown proceedure in (at ideal) an inert atmosphere,with no liquid hitting it. You typically need a good heat treatment furnace with a temperature controller that’s very accurate to harden air hardening tool steels properly. There are also steels like 17-4PH and 15-5PH which are both stainless and are precipitation hardened. Don’t ask me to explain how that one works 😂

It’s difficult to explain why steels harden in these 3 ways- if you would like a good book to go into understanding hardening steels more like this, I recommend the book “Tool Steel Simplified” by Palmer & Luerssen. They go into explaining the mechanisms of how that works and how carbides form in the steel, and a lot of other things like eutectic diagrams.

There are types of steels that are what we call “damascus” in modern terms, that are completely different from anything described here- look up Takefu Specialty Steels in Japan. Many years ago when I lived there, I purchased a knife that had brass folded into the steel blade, and for many years, no professional smith I met could explain how it was physically made.

Eventually I found out it was specialty clad steel, which is made with a special process, and it allows things like copper and brass and non-ferrous metals to be folded in with steels which would normally be physically impossible. They have a really good Instagram account, and it was thanks to that that I finally found how my Saiji Takeshi blades were made using a special type of steel from Takefu.

There is also Baker Forge, who makes a multicolored “damascus” which involves using chemical baths to change the surface oxidation of some of the additives to get colors you would never see possible.

Nitre Bluing is a process used when you see blue and purple mottled colored damascus on many high end blades. It is usually blues and purples and sometimes slight hues of orange, and it’s my understanding specialty nitre bluing salts are used to achieve that effect.

The best book written on modern damascus steel I know of is “The Pattern Welded Blade” by Jim Hrisoulas wich is on my shelf.

Hopefully this information helps some of you

Decorative metal damascene is called Mokume Gane, I have a nice book of that name.

it did, thank you

That’s not a problem with the show, it’s a problem with the viewer.

The worst part of Forged in Fire is none of the participants get to keep what they make because the show is shot in New York. New York has a law where any weapon manufactured for a TV or movie production is the property of the show.

If I was going to all that work to make something for a TV show, I’d want to keep it, unless it was a paid contract to make it for them. If I’m not getting paid, it’s mine – but not in NY.

If anyone is interested in learning more about Wootz Damascus steel, I currently forge it and run a website to help people in understanding how to forge it.

https://www.wootzsmithforum.com/

I also have several examples on my Instagram of finished Wootz Damascus pieces. https://www.instagram.com/besslenbladeworks/

There was a man in North Georgia (the U.S. state) named Ivan Boggs who would buy used files and rasps from machines shops to turn into folded steel knives. I haven’t spoken to him in 20 years but I remember him saying that he usually only folded his “production grade” knives about 40 to 45 times unless a person requested more. I have a 3″ work knife from him and my mother still uses her patch knife for muzzle loading. Both hold a sharp working edge forever.

If he’s still around he’s in his 90s now but I’ve seen some of his stuff go for well over $500 at auctions.

I believe he turns 94 this year if I remember correctly, and he’s still alive in Cleveland GA last I heard (I’m from north GA and he’s something of a legend and well known around here). I don’t think he’s smithing anymore though.

This is all nice and well, but I don’t think we really need the desperate stuff people did hundreds of years ago to get decent quality when we have modern techniques to get better results right? I mean it’s fun for hobbyist it seems, and that’s fine, but let’s not ignore we are not living in 1023.

And because it is for hobbyist we don’t need it to be ‘perfect’.

Also we don’t do swords fighting of the kind where the blade migh shatter with knives/swords that are done by hobbyists or are made to be decorative anymore I would hope. If you are into fencing as a sport you buy professional stuff made with modern techniques and not some decorative ebay special.

There’s a much more recent knife blade mystery. How did F.J. Richtig forge steel blades tough enough to be hammered through railroad spikes? He did that demo so often that he had a shelf full of curled up railroad spikes he’d hammered blades most of the way through about every inch along their length.

But note that the warranty he included with his knives said the warranty was voided if such abuse was done.

Railroad spikes aren’t hard, they’re tough. Wouldn’t be especially challenging to purpose make a knife that could do that demo. A thicker profile with a more more chisel tapered edge would do it. Make it out of something like 1070 steel and it will get hard enough but still flexible enough to not need differential tempering to survive it.

I’ve got a few combat ready swords made by a place who’s demos at renfaires are hacking apart other places swords with no damage to theirs, also have a similar warranty.

So does a “Real Damascus Steel Knife” knife have to be expensive? Naaaw…

* MOHID ENT Damascus Knives Damascus Steel Knife – Fixed Blade Knives – Real Damascus Hunting Knife – Best Gut Hook Skinning Knife With Leather Sheath Belt Loop Brand: MOHID ENT 4.5 out of 5 stars 57 ratings 50+ bought in past month $19.99 [Non-Affiliated Link]:

https://www.amazon.com/Damascus-Knives-Steel-Knife-Skinning/dp/B09DBZKNP9/

Yeah, take “Real Damascus Steel” with a big pinch of salt. Just search for “Making Fake Damascus Steel” on YouTube – a broad range of techniques will pop up. But get your ad-blocker ready for battle!

Then there is this:

Damascus steel with 300 blades for a safety razor.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vbi8geS4xMQ

I asked my Amazon supplier if the knife was forged. He said “Absolutely!”

Damascus barrels had their place at one time, but the fairly extreme variation in quality means that shooting a modern high pressure load in some of those old rifles is a Darwin Award waiting to happen. When I was young my dad made me promise never to actually shoot one.

When I read the headline for this (very good) article, I thought it was the setup to a punchline, which my brain then autocompleted, and I’ll now share here:

When is Damascus Steel not Damascus Steel?

When it’s a forgery.

I’m sorry, I’ll go now,

Please come back soon

Fitzweener, unfortunately your blade did not make the cut. Surrender your blade and leave the forge.

Thanks for this article. I get so sick of modern smiths (a handful of whom know better) referring to their pattern-welded work as damascus or damascine.

I agree that the work is impressive, but its good to be clear about the different refining and forging techniques so that people are less confused by the terminology. Confusion makes researching proper techniques and the history of the technology so much harder.

(As an aside, I wanted to slap Patrick Rothfuss when he repeatedly misused the term “pig iron.”)

For those that don’t know (I am guessing that Beowulf does, from his comment) “damascene” is something else entirely, and is very pretty, and very time consuming. I rather want to try it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Damascening