Today’s pressurized water reactors (PWRs) are marvels of nuclear fission technology that enable gigawatt-scale power stations in a very compact space. Though they are extremely safe, with only the TMI-2 accident releasing a negligible amount of radioactive isotopes into the environment per the NRC, the company Deep Fission reckons that they can make PWRs even safer by stuffing them into a 1 mile (1.6 km) deep borehole.

Their proposed DB-PWR design is currently in pre-application review at the NRC where their whitepaper and 2025-era regulatory engagement plan can be found as well. It appears that this year they renamed the reactor to Deep Fission Borehole Reactor 1 (DFBR-1). In each 30″ (76.2 cm) borehole a single 45 MWt DFBR-1 microreactor will be installed, with most of the primary loop contained within the reactor module.

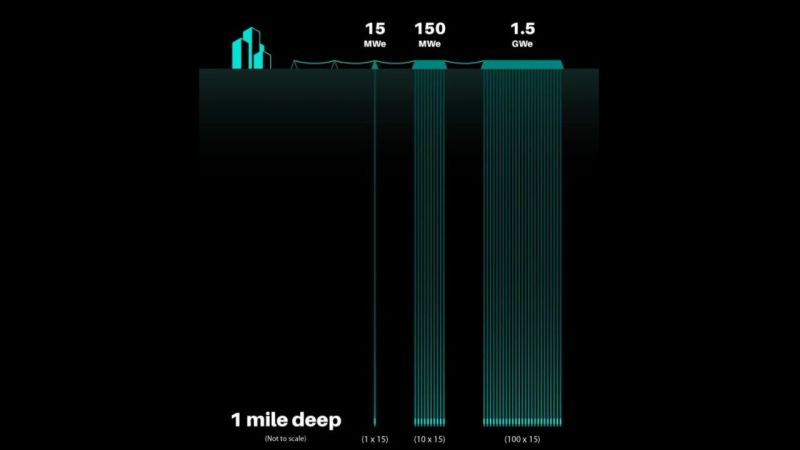

As for the rationale for all of this, at the suggested depth the pressure would be equivalent to that inside the PWR, with in addition a column of water between it and the surface, which is claimed to provide a lot of safety and also negates the need for a concrete containment structure and similar PWR safety features. Of course, with the steam generator located at the bottom of the borehole, said steam has to be brought up all the way to the surface to generate a projected 15 MWe via the steam turbine, and there are also sampling tubes travelling all the way down to the primary loop in addition to ropes to haul the thing back up for replacing the standard LEU PWR fuel rods.

Whether this level of outside-the-box-thinking is a genius or absolutely daft idea remains to be seen, with it so far making inroads in the DoE’s advanced reactor program. The company targets having its first reactor online by 2026. Among its competition are projects like TerraPower’s Natrium which are already under construction and offer much more power per reactor, along with Natrium in particular also providing built-in grid-level storage.

One thing is definitely for certain, and that is that the commercial power sector in the US has stopped being mind-numbingly boring.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v0afQ6w3Bjw

Regular reactors are perfectly safe and you want to be able to access them.

It’s such a good solution with such an amazing track record that I’m beginning to suspect that some of these people don’t actually want to decarbonize and produce clean energy, they want to juice certain industrial sectors and also create an NGO where a bunch of their friends can have $400k checking email jobs and pay off the loans for their master’s degree.

Unfortunate for the renewables is that nuclear energy is relatively low carbon emitting. And inertia of old industry is heavy. But the wheel of history is turning!

Believe in Sun, the best fusion reactor, which is for us ready already billions of years:)

Germany has had to scale back it’s renewables expansion due to grid management problems caused by a massive overcapacity from wind and solar which, unlike nuclear and older technologies, cannot be scaled back to compensate for lower demand.

And that’s without getting into the issues caused their inability to generate or absorb reactive power.

At one stage France was buying German renewable energy for negative Euros via the European Electricity Exchange (EEX), i.e. Germany was in effect, paying France to use their excess capacity.

Germany has had to scale back it’s renewables expansion due to grid management problems caused by a massive overcapacity from wind and solar which, unlike nuclear and older technologies, cannot be scaled back to compensate for lower demand.

And that’s without getting into the issues caused their inability to generate or absorb reactive power.

At one stage France was buying German renewable energy for negative Euros via the European Electricity Exchange (EEX), i.e. Germany was in effect, paying France to use their excess capacity.

If a wind turbine or photovoltaic solar power plant cannot scale back its output, the design is defective.

WHAT. That is the exact opposite of the truth. Wind and solar generation can be adjusted arbitrarily from zero right up to whatever the total collectable energy is at the moment.

Coal and nuclear plants are unable to go below a fixed minimum power output without being completely shut down, and that power must be used in the grid. This is the “baseload”, and contrary to the propaganda put out by the fossil fuel industry, is not a benefit of those technologies but the consequence of their inflexibility.

It CAN be adjusted, but it currently isn’t, because that would require that solar inverters are tied into some power exchange scheme. That would require regulation and someone would need to support servers for all those thousands of small 5kw inverters and manufacturers of those inverters would need to agree on some protocol. Probably it could be realized with current data over powerlines protocols, but I think this would require some new extensions to this protocol. Technically very possible, politically hard.

@Chris Maple

The converter designs aren’t defective, just limited. In the ‘stampede’ to get as much renewable capacity online as quickly as possible, no one foresaw a point where the available capacity would be a problem. They obviously thought they had plenty of time to improve the designs.

@pelrun

The exact opposite eh :)

The beneficiary of all this isn’t supposed to be the renewables industry, it’s supposed to be our own future. If we have a solution that’s workable now we should just use it. All of the energy we use is sun-energy, it’s just a question of which route it takes.

US nuclear power industry was doing well, until idiots like Jack Welsh (and his clones) started corner cutting and skipping regular/planned maintenance in favor of juicy investor returns. Oh, they also fired most of US engineers and brought cheap contractors form overseas yes, late 1970s – early 1980s, Jack Welsh again, his idea of NAFTA was “fire everyone who is not a manager, then gradually fire managers as well”. Brilliant, right?

Business failure (and basically ZERO responsibility) was the main reason, and coal burning is not safer either, belching smoke like there is no tomorrow WORLDWIDE (keep in mind the number of coal-burning plants grew astronomically since 1980s, China, etc – because things are just darn cheap to build and run).

Spoiler – I personally knew one of the fired nuclear plant engineers, no, not manager, ENGINEER, the one who design, builds and then maintain the thing. His last project was the NY’s Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant, and he was basically fired on the spot, no reason, and replaced with the cheapest contractors they found elsewhere, zero experience, but three or four “degrees” from places like University of Mumbai.

The story continues – the plant never reached operational level (I wonder why, right? firing all the engineers and replacing with high school graduates with fake diplomas, what can possibly go wrong) and was deemed “too expensive” and basically trashed. I trust his words more than fake stories in the news, Greenpeace, greenshmease, it was dumb management decisions and nothing else, spend all the money and hire the cheapest labor.

Translation – what trashed US nuclear power plants was bean-counting, and then proper regulations pretty much shut it all down until I’d say early 1990s. By then it was too late to restore the US expertise, and H1B visas were making it basically impossible. Rewind to around mid-1990s when I asked my friend WITH EXPERIENCE if he’ll consider looking for a job. He laughed. Programming, he said, pays better, and the hell with the companies who are falling behind with their R&D. Mid-1990s. In about ten years India would have its pebble bed reactor proof of concept running, so I’ll stop at that.

“what trashed US nuclear power plants was bean-counting”

There are a number of books about the negative effects in the US of these VULTURES:

“Private equity is stock in a private company that does not offer stock to the general public. Instead, it is offered to specialized investment funds and limited partnerships that take an active role in managing and structuring the companies.”

A major US manufacturer of model rocket kits and rocket motors in a presentation at a recent convention explained why their motors were suddenly failing catastrophically: their motor casing manufacturer had sold out to a PE firm and had somehow “forgotten” how to make good casings.

PEs come in, fire everyone who knows what they’re doing because they cost too much, and replace them with cheap labor who don’t know what they’re doing. Maximum profit uber alles. The business fails? So what? (see article below)

Ask Grok: What negative effects does private equity financing have on nuclear power plant construction and operation?

When Private-Equity Firms Bankrupt Their Own Companies

Private-equity firms can succeed when their companies, customers, and employees fail. It’s a broken system.

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2023/05/private-equity-firms-bankruptcies-plunder-book/673896/

Regardless, still outrageously lower fatalities per watt, like orders of magnitude, even compared to solar

It used to take thousands of human sacrifices a year to keep the Sun running. Now that we know we can control it by paying taxes, what’s all the hubub, bub?

My tin-foil theory is that the German Green movement was hijacked by German coal producers to undermine nuclear power.

Or just people who hate Germany generally

Considering the russkies clandestine supported any anti nuclear endevours in west germany with the aim of screwing with nato and furthering european long term energy dependancies of the soviet union and later Russian energies, the green movement always was/has been a tool to divide and conquer west europe and later EU.

Nuclear is safe, cheap, and quick to deploy. Pick two.

Compared to what? It’s all three compared to other methods

Planes are also perfectly safe, but every once in a while…

And there lies one of the rubs, the one time it goes bad the bad can be pretty pretty bad.

And of course there is the issue with radioactive waste, both from the use as well as from the eventual retirement of a plant. Where the issue is not only where do you put it but also how will you transport it there.

Any response to Chris Maple? Because he’s right, you can easily change the vanes of a wind turbine or put a brake on it or rotate it out of the wind to reduce capacity, to name a few thing that pop to mind.

And for solar, what is easier than shoving a (partial) barrier over a solar panel? Or rotating it away from the sun? It’s not rocket science is it now?

Pumping water and steam up and down a borehole with a running reactor at the bottom sounds like a good way to create lots of radioactively contaminated water and leak it into the ground water table very effectively.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WJlZLG9UXSY

What does “radioactively contaminated” mean?

You mean, like Radium in basalt? There’s no radioactive water. You can have water contaminated with radioactive elements (and even this isn’t clear, many elements are perfectly safe and radioactive). The radioactivity by itself isn’t bad. Some elements like heavy metals are bad even when not radioactive. The radioactivity is a pain because it can change a bio-safe element into a bio-unsafe element.

i feel like i must’ve missed the HackADay article where we figured out how to safely dispose of all the highly radioactive waste that all these microreactors produce.

It’s already a mile down. Maybe just leave it there?

Yeah, burying our toxic waste has always worked out so well…

A mile underground may be ‘safe’, until something goes wrong. Difficult to inspect and maintain at that depth. Still need a means to monitor and control. Some pretty long cables. Not everywhere is entirely earthquake proof either. We only hear about the bad ones, we feel… High pressure, and a mile long bore for a rifle barrel. If it does rupture, it’ll shoot stuff a long way. Not well contained…

Not exactly a huge amount of power from each hole either. They’ll want to do thousands of them. Why can’t we just focus on getting fusion working?

That’s why actual deep borehole disposal is at least 3 miles deep, so when the containers inevitably degrade there’s enough stuff piled on top that it takes a million years to leak out – by which time it won’t be very radioactive any longer because all the nastiest stuff has decayed out.

Borehole disposal is not anywhere close to operational. Its based on a lot of speculations and assumptions. Not somewhere id stick high activity waste.

You said it always worked out so well? Was that sarcasm?

Less than 60 people have been killed by Nuclear power in the United States. That’s even safer than solar and wind energy!

Burying our toxic waste that deep actually has a pretty fantastic track record if you ignore the rhetorical snark

The point of deep borehole disposal is a bit deeper than that.

You’re supposed to plug the hole after you leave the waste in, not leave it open and fill it with water.

So just heavy metal poisoning? What’s the holdup?

most of the 10k year waste goes by another name, useful nuclear fuel. the worst isotopes are the short lived ones. you burn those off, then it becomes safe enough where you can extract and purify the useful isotopes and put it back into the reactor. breeder reactors make the whole point moot by burning everything.

If it’s highly radioactive, you can use it for fuel. If it’s truly waste (less radioactive) you can put it back where you mined it in the first place.

Not to mention the cost…

Maybe there should be one. I added this to their tip line…

https://www.deepisolation.com/

Or you could drill that 1mile hole and not put a reactor down there. Just pump down water and use the geothermal energy.

Geothermal doesn’t produce a whole lot of power per area because the temperature difference isn’t that great for a steam turbine, and the site goes cold in 20-30 years of continuous use, so you have to keep drilling new boreholes on new sites continuously.

This is because the earth’s core only gives off about 50 milliWatts of thermal power per square meter on average. It’s only hot a couple miles down there because it’s had millions of years to warm up from the heat escaping the earth’s core, which makes geothermal power a sort of a fossil fuel. Once you cool the rock down, it takes a very long time to heat back up.

That’s why geothermal power only makes sense in special places where the earth’s crust is thin and the heat flux is well above average, like in Iceland. You can’t just drill a hole anywhere and expect to get useful power out, at least for very long.

The other kind of geothermal heat, like ground source heat pumps, are actually solar heat collectors tapping in to the heat coming from above, not from below.

Boreholes for heat pumps must be seasonally heat (summer) and cool (winter) the surrounding material of borehole.

Boreholes for geothermal heating are heated by internal heat of our planet.

Boreholes for nuclear energy? Nah, maybe better than surface plant. Use it, archive the position and drill another one.

And plant panels, turbines and batteries of course.

I was about to say that.. sounds like geothermal with extra steps.

Since they will need to bore the holes anyway : build the concrete containment structure, for added safety, and install the steam generator down there also. Bring only the power cables to the surface. Easier to fix a broken cable than a tube leaking very hot water.

That was my first thought as well; but then I wondered if the volume occupied by the alternators might be a large percentage of the area occupied by a nuclear plant. So I asked ChatGPT, which summarized the answer:

“Only about 0.01%–0.2% of a nuclear plant’s occupied land area is devoted to the alternators themselves, even if you count the entire turbine hall.”

I imagine that underground the percentage might be higher because there probably wouldn’t be as much need for things like the exclusion zones, support buildings, parking, etc that ChatGPT mentions.

That suggests to me that allowing 10% of the floor area for alternators is generous. If that’s the case, then yes, generating electricity directly beside the reactor instead of on the surface seems the best way to proceed.

But maybe keeping the alternators sufficiently cool would be a problem? Then again, THAT heat could be piped to the surface and perhaps used. So I’d be very interested to hear compelling arguments against putting the alternators underground.

The turbines and generators have parts that need to be precisely aligned after installation and replaced periodically during scheduled maintenance, such as bearings, so dropping them down the hole would just be making life more difficult for yourself.

“Alternators”? Like in a car? You mean generators? (An alternator is smaller than a loaf of bread, so they probably wouldn’t give you much power in a nuclear generator). Oh wait, you got all this nonsense from “AI”? Nevermind, I’m wasting my breath.

It’s called an “alternator” because it’s a specific type of generator that generates alternating current.

Size doesn’t matter here. Most power plant generators are, in fact, alternators, and it’s not weird to refer to them as such. Check the examples on the wikipedia page:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alternator

Of course, the common car alternators make this extra confusing, since they use voltage regulators and rectifiers to convert their three-phase alternating current to the dc voltage that cars expect.

Funny. My last Jeep had a generator, not an alternator. And a gas-powered generator produces electricity with its alternator.

A steam generator in a thermal power plant is pretty big. But the alternator in a hydro plant can be even bigger. The biggest I’ve been close to had a shaft a meter in diameter. The stator was more than 10 meters in diameter. It produced 60 Hz power, but turned only at 72 rpm.

Is there a clear definition? It’s probably more context. “A generator produces DC current. An alternator produces AC current.” was true in 1960. Now, your car alternator produces DC current, acting more like what we called a generator.

A gas power plant produces electricity by a turbogenerator. A hydro plant produces electricity by a turbine-powered alternator.

Take your pick. There are better crusades to die on.

Before automotive alternators came into use, made possible by power semiconductors, automotive generators used mechanical commutation to produce DC. Both the copper commutator segments and the brushes were significant wear items significantly limiting generator lifespan. Voltage control was very crude.

Yeah, my first Jeep (a 1953) had no semiconductors whatsoever. Not even a single diode. The generator brushes were a routine replacement issue, and it was awful at actually making electricity: it would not charge at all at idle. The voltage “regulator” was just a relay: bang:bang control.

To add to what [Chris] says:

I think a straightforward definition of alternator & generator was plenty unclear in 1960 and earlier too. In many ways, the DC generators in old cars were really no more “dc generators” than the automotive alternators that replaced them! They use magnets to generate alternating current in their field windings, just like an alternator.

The only difference is that an old automotive generator rectifies that waveform to (choppy) dc by mechanically switching the direction of current flow as it spins, whereas a modern car alternator uses diodes to do the same trick, and still puts out direct current.

(as an aside, the familiar term for a mechanically-commutated dc generator is a “dynamo”, but my sense is that the automotive ones were almost always just referred to as “generators” not “dynamos”)

Delco had the Delcotron, Chrysler had the Alternator both were registered trademarks. It’s a definite portmanteau. Generators didn’t charge at idle your car radio with 6 tubes was more than headlights on both worse and it’s cold outside. Better have a good battery.

Not convinced that ChatGPT is correct…

As they say: Slop In, Slop Out.

Makes sense to me. If we can bottle one up to run in a submarine at classified depts, then building one to be stationary in a pool at the bottom of a hole should not be that much of an engineering lift. Not “easy” by any means, but the math should be pretty straight forward.

Not to mention the thermal losses of even the best insulated pipes over that length.

“Ropes”? My money’s on daft.

Okay, whatever you guys need to assuage the ludicrous irrational fear everyone has. Sure, build everything a mile deep for no reason at enormous added expense, whatever. Just build them somewhere.

Well in fairness here its a very small borehole – should actually be pretty cheap as large infrastructure projects go. And putting your small reactor deep down and out the way potentially right next to the consumers can have merit. Doesn’t seem the most practical option as a rule, but it might just wind up being more practical to supply a decent and fairly rapidly scaleable baseline power with very little ground footprint right at the point of consumption to reduce the need for a higher capacity transmission grid or more expensive backup power options.

I suspect this concept is an idea that only really looks good for relatively isolated and geologically stable places – For instance some of the smaller islands around Scotland could have one or two of these now, somewhat revitalising those islands with sufficiently abundant energy that they might just need to add another as more people and industry (likely ocean based) set up there again now they are really able to really function in at least a 20th century way.

That would work against the British government’s policy of de-industrialising and depopulating Scotland so they can continue plundering its resources.

Current target – Fishing Industry.

The Scottish ‘Parliament’ doesn’t need the British government’s assistance for that. It’s doing a fine job all by itself.

Once 51% of population are on the tit democracy is over.

They vote for ‘more tit’, everybody else either starts sucking or votes with feet.

Government soon runs out of other peoples money to spend.

Bet the English pound will be the first large modern currency to fail.

But there are so many mismanaged big contenders. US$, Euro, Yuan, Pound.

To say nothing of the mismanaged little ones. Aus$, Yen, Roble, 51ststate$, Peso, Rupee…

I guess writing about hacks got boring…

Boring holes. This is a hack of a nuclear industrialists, easy doable. You need only boring machine and suitable nuclear reactor type “all in one pipe” :)

PWRs aren’t exactly modern tech. And the pressurised part is a huge part of the risk. They also require a ton of maintenance and care to operate.

A more modern design with passive safety and simpler operation makes more sense if you’re putting it underground.

And why so deep? That’s just a huge added cost, really only there to ally the fears of NIMBYs.

Like having an electric car and going on a diesel powered vegan cruise. As long as the smoke is elsewhere the smug feels snug at home.

A deep and narrow hole, filled with water, with a nuclear reactor core at the bottom (pulled up for servicing by ropes no less).

I can imagine a few risk scenarios that involve that beast shooting out of the hole like a gas-propelled gerbil.

Gerbil with escape velocity?

Can’t blame it.

Heard it was going to be shipped to SF.

Those peddling such design as “safe” should have no problems building their house over it AND living there with their families. Am I right or am I right?

Considering how many people think fracking made flames shoot out of the kitchen faucets, I can’t see this going well.

‘think’? WTF.

Yeah people ‘think’ that because the regular news and authorities report it.

If you get groundwater, and you get natural gas dissolved/leaked into the pockets of groundwater, then what do you think happens?

Obviously it won’t be flames unless you get it ignited, but you don’t immediately expect gas from a water tap though.

And I’m sure you will also deny it would be an issue if a meltdown caused a reactor core to hit the groundwater level and the effect of the steam explosion and radioactive contamination people will then ‘think’ to observe.

Have worked in the petroleum industry drilling holes this deep. Not gonna rule out those bastards making daft things work, but the idea is daft. The holes and anything at the bottom of them need routine maintenance and interact with (usually very salty) groundwater. Rock is crumbly and imperfect, especially under high pressure.

Im not understanding something here. 1. Why is it necessary to go that deep? Ground level reactors dont require that much shielding. 2. If the primary steam loop and all that is above ground, why is it that much safer? In other words what problem are we solving that mitigates the crazy maintenance and surveillance process. Also, what does a refueling cycle look like?