If you get a chance to visit a computer history museum and see some of the very old computers, you’ll think they took up a full room. But if you ask, you’ll often find that the power supply was in another room and the cooling system was in yet another. So when you get a computer that fit on, say, a large desk and maybe have a few tape drives all together in a normal-sized office, people thought of it as “small.” We’re seeing a similar evolution in particle accelerators, which, a new startup company says, can be room-sized according to a post by [Charles Q. Choi] over at IEEE Spectrum.

Usually, when you think of a particle accelerator, you think of a giant housing like the 3.2-kilometer-long SLAC accelerator. That’s because these machines use magnets to accelerate the particles, and just like a car needs a certain distance to get to a particular speed, you have to have room for the particle to accelerate to the desired velocity.

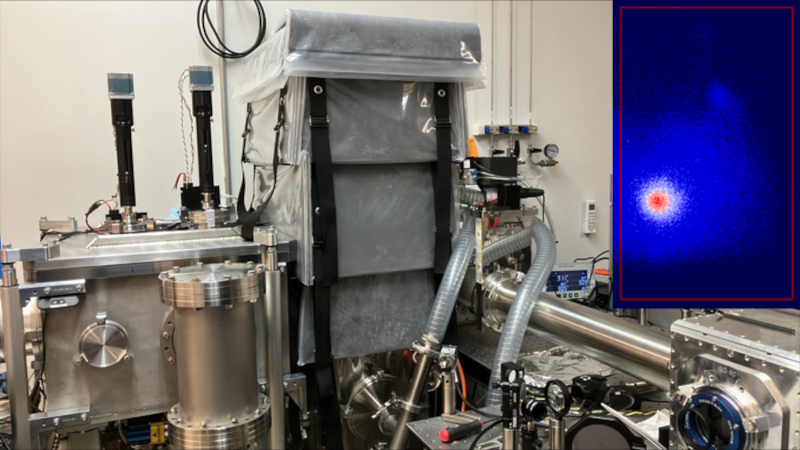

A relatively new technique, though, doesn’t use magnets. Instead, very powerful (but very short) laser pulses create plasma from gas. The plasma oscillates in the wake of the laser, accelerating electrons to relativistic speeds. These so-called wakefield accelerators can, in theory, produce very high-energy electrons and don’t need much space to do it.

The startup company, TAU Systems, is about to roll out a commercial system that can generate 60 to 100 MeV at 100 Hz. They also intend to increase the output over time. For reference, SLAC generates 50,000 MeV. But, then again, it takes two miles of raceway to do it.

The initial market is likely to be radiation testing for space electronics. Higher energies will open the door to next-generation X-ray lithography for IC production, and more. There are likely applications for accelerated electrons that we don’t see today because it isn’t feasible to generate them without a massive facility.

On the other hand, don’t get your checkbook out yet. The units will cost about $10 million at the bottom end. Still a bargain compared to the alternatives.

You can do some of this now on a chip. Particle accelerators have come a long way.

Photo from Tau Systems.

Oh this is so exciting!! IMHO electron beams or the way to go for rad testing for space environments. You get a scale that resembles closer to a laser system while getting some of the penetration power of something like a proton or heavy ion beam. Best of both worlds.

Of course, the devil is in the details concerning spot size, penetration depth, charge deposition etc.

Research is actively being conducted so that we can draw equivalence LET’s produced by between e-beams (and laser) systems, and old fashion proton and heavy ion testing.

The Varian Truebeam radiation therapy system contains a LINAC in the 22Mev range. It’s definitely less than room size. Cost is about $4M.

I’ve worked on similar systems, along with small cyclotrons. The equipment itself is not very large; it’s the radiation shielding that takes up all of the volume and weight. The cyclotrons we built were used to generate radioisotopes for PET, a process that created quite a lot of “waste” radiation that had to be dealt with.

My understanding is that the plasma oscillates in the wake of the electron beam. The laser converts the gas to plasma, the incoming electron beam repels free electrons in the plasma creating a positively charged tube, and then those repelled electrons are pulled back into the positively charged tube in time to repel the tail end of the beam, giving it a forward kick. It’s a way to transfer energy/momentum from the front of the beam to the back of the beam. There’s no free lunch happening.

Also, at SLAC the beam acceleration is accomplished with RF fields generated by klystrons. The magnets are used for steering and focusing, but they don’t add energy to the beam.

It’s cool to see this technique being commercialized. I was a summer intern with one of the first groups doing wakefield experiments in 2001.

“That’s because these machines use magnets to accelerate the particles” magnetic fields can not do work on charged particles. The F dot dv is zero.

gonna file this under ‘whoa if true’

It’s true. SLAC and every other accelerator use directive fields to accelerate. Circular machines use magnets to bend the ban into a circle it a spiral so they can, more compactly, reuse the accelerating electrodes.

I remember hearing from the wife of one of the VPs at Tau (a physicist herself) that Tau got the money they needed to start to commercialize. Very exciting to see an article on the company.

Author needs to correct his assertion that magnets accelerate particles. As others have said, they do not do that and physically cannot do that. In traditional accelerators it is RF power pumped into resonant cavities that cause the particle to see an accelerating field when introduced say the correct time.

Being picky about it, magnetic fields do accelerate moving charged particles. But the acceleration is orthogonal to the direction of motion, so the energy of the particles remains unchanged.

The trick is to use circularly polarized light fields, so the Lorentz (magnetic) force on a charged particle is always directed forwards.

I don´t know how old is people here, but cathodic rays tubes for the screens of all old TVs where particle accelerators, and the basis for X-ray machines used by dentists nowdays.

Aww, I was hoping a reader here had built one.

Don’t I remember an Amateur Scientist column about building one using a Van de Graaff generator?

I know I’m comparing apples to black holes but in the ’80s anyone that owned a square TV with a tube for a screenin it owned a particle accelerator. It had electron guns inside that accelerated, again through magnetism. They were a lot cheaper. I recommend scientists use these instead. You could probably achieve fusion with some of these TVs back in the day. Just having a little fun…

As often happens, something about the intro didn’t ring true. Sith Lord Google confirms my recollection:

“The first successful circular particle accelerator, Ernest Lawrence’s cyclotron from 1930, was tiny, with a vacuum chamber less than 5 inches (about 11 cm) in diameter, yet it achieved a significant breakthrough by accelerating hydrogen ions to 80,000 electronvolts, paving the way for much larger machines like the Large Hadron Collider. “

“Usually, when you think of a particle accelerator, you think of a giant housing like the 3.2-kilometer-long SLAC accelerator. That’s because these machines use magnets to accelerate the particles”

This is just plain wrong. SLAC in particular[*] does not use magnets, because it’s a a linear accelerator. They do however have rather a lot of klystrons.

Magnets are used to confine the beam in non-linear accelerators. This has the advantage that your acceleration equipment gets more than one go at the beam of particles, but the disadvantage that you bleed off energy as synchrotron radiation.

[*] SLAC does have an electron/positron storage ring which of course uses magnets, but that’s not part of the accelerator.

SLAC and every other accelerator use electric fields to accelerate. Circular machines use magnets to bend the beam into a circle or a spiral so they can, more compactly, reuse the accelerating electrodes.