Many projects on these pages do clever things with video. Whether it’s digital or analogue, it’s certain our community can push a humble microcontroller to the limit of its capability. But sometimes the terminology is a little casually applied, and in particular with video there’s an obvious example. We say “PAL”, or “NTSC” to refer to any composite video signal, and perhaps it’s time to delve beyond that into the colour systems those letters convey.

Know Your Sub-carriers From Your Sync Pulses

A video system of the type we’re used to is dot-sequential. It splits an image into pixels and transmits them sequentially, pixel by pixel and line by line. This is the same for an analogue video system as it is for many digital bitmap formats. In the case of a fully analogue TV system there is no individual pixel counting, instead the camera scans across each line in a continuous movement to generate an analogue waveform representing the intensity of light. If you add in a synchronisation pulse at the end of each line and another at the end of each frame you have a video signal.

But crucially it’s not a composite video signal, because it contains only luminance information. It’s a black-and-white image. The first broadcast TV systems as for example the British 405 line and American 525 line systems worked in exactly this way, with the addition of a separate carrier for their accompanying sound.

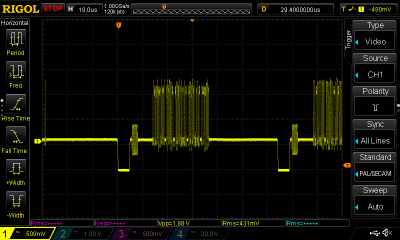

The story of the NTSC colour TV standard’s gestation in the late 1940s is well known, and the scale of their achievement remains impressive today. NTSC, and PAL after it, are both compatible standards, which means they transmit the colour information alongside that black-and-white video, such that it doesn’t interfere with the experience of a viewer watching on a black-and-white receiver. They do this by adding a sub-carrier modulated with the colour information, at a frequency high enough to minimise its visibility on-screen. for NTSC this is 3.578MHz, while for PAL it’s 4.433MHz. These frequencies are chosen to fall between harmonics of the line frequency. It’s this combined signal which can justifiably be called composite video, and in the past we’ve descended into some of the complexities of its waveform.

It’s Your SDR’s I and Q, But Sixty Years Earlier

An analogue colour TV camera produces three video signals, one for each of the red, green, and blue components of the picture. Should you combine all three you arrive at that black-and-white video waveform, referred to as the luminance, or as Y. The colour information is then reduced to two further signals by computing the difference between the red and the luminance, or R-Y, and the blue and the luminance, or B-Y. These are then phase modulated as I-Q vectors onto the colour sub-carrier in the same way as happens in a software-defined radio.

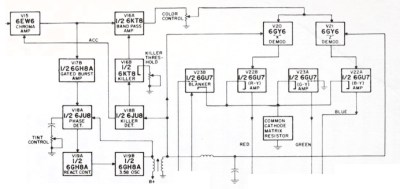

At the receiver end, the decoder isolates the sub-carrier, I-Q demodulates it, and then rebuilds the R, G, and B, with a summing matrix. To successfully I-Q demodulate the sub-carrier it’s necessary to have a phase synchronised crystal oscillator, this synchronisation is achieved by sending out a short burst of the colour sub-carrier on its own at the start of the line. The decoder has a phase-locked-loop in order to perform the synchronisation.

So, Why The PAL Delay Line?

There in a few paragraphs, is the essence of NTSC colour television. How is PAL different? In essence, PAL is NTSC, with some improvements to correct phase errors in the resulting picture. PAL stands for Phase Alternate Line, and means that the phase of those I and Q modulated signals swaps every line. The decoder is similar to an NTSC one and indeed an NTSC decoder set to that 4.433MHz sub-carrier could do a job of decoding it, but a fully-kitted out PAL decoder includes a one-line delay line to cancel out phase differences between adjacent lines. Nowadays the whole thing is done in the digital domain in an integrated circuit that probably also decodes other standards such as the French SECAM, but back in the day a PAL decoder was a foot-square analogue board covered in juicy parts highly prized by the teenage me. Since it was under a Telefunken patent there were manufacturers, in particular those from Japan, who would try to make decoders that didn’t infringe on that IP. Their usual approach was to create two NTSC decoders, one for each phase-swapped line.

So if you use “NTSC” to mean “525-line” and “PAL” to mean “625-line”, then everyone will understand what you mean. But make sure you’re including that colour sub-carrier, or you might be misleading someone.

“How Do PAL And NTSC Really Work?” – DOES “never the same color” work? * cue rimshot *

Never TWICE same color

Why not mention SECAM which was used in Soviet USSR, Africa, Europe and other countries.

By “Europe” you must mean “France”.

SECAM is mentioned in the article.

“Soviet USSR, Africa, Europe and other countries”: None of those three places are countries.

I lived in Africa for years, and visited several countries there. None used SECAM. Some others did, but it is certainly not exclusive.

Even in Europe, the majority of countries used PAL. It was principally only seen in France.

You forgot Belarus.

And the reason why France used it was to protect their domestic market and manufacturers Can’t import PAL or NTSC televisions because they won’t work with French TV broadcast. The reason why African countries used SECAM was because of French colonialism.

The reason why the USSR used it was because it forced you to watch the corrupt capitalist broadcasts from the other side of the iron curtain in black and white, while the much more advanced Communist TV broadcasts were in color – assuming you were granted the permission to buy a television.

So you could say that the SECAM was a product of jingoism.

You talking absolute bullshit nonsense because of lack of knowledge and washed brain by the cheap western propaganda. USSR is a country , biggest country in that time .SECAM is not political choice but technical.SECAM is far superior to PAL because don’t care about phase problems at all because it’s frequency modulated color signal .It’s important for long analog distance transmission lines in USSR including satellite that was first used to cover this very big country .As well they have larger bandwidth 6.5 MHz instead 5.5 PAL .Also as far as I know SECAM is patent free or at least non discriminatory that giving everybody right to produce receivers .FORMER East Europe also had SECAM because of technical suoeriowand i order to easily exchange programs with USSR and other socialist countries. So,all you said is a nonsense bullshit but I don’t spend my valuable time to describe how stupid is what you talk. Please don’t mix technology with politics if you are not aware .

Nice cope, soviet apologist. What about Katyn massacre though, or millions who perished in gulags? Were they covered by patents?

Hi! The former East Germany (GDR) had used SECAM, too.

In addition to pure black/white transmissions,

which were still being used (if the source material had no color, for example).

Then, many GDR color TVs had an provision for an optional PAL module, to receive color TV programme from West Germany (FRG).

(In the later years, it was an open secret that GDR citizens watched west TV, so it had been silently tolerated in order to not make citizens unhappy.

Some terrestial antennas on apartment buildings even pointed to west transmitters.)

That being said, color TV sort of was a luxury in GDR.

Most people or families could been happy to own a TV, at all.

Black/white portable TVs were still in wide use by late 80s.

It really was a different world in retrospect

B/w portable TVs often served as monitors for homebrew computers.

Such as AC1, KC85, Spectrum clones or the C64 (imported from W-Germany).

Speaking about SECAM..

If I do remember correctly, the French SECAM and the SECAM used in other countries wasn’t exactly same.

So it sometimes wasn’t possible to receive SECAM signals from France with a foreign SECAM TV set.

But maybe my memory plays tricks on me here.

If we must pick nits, USSR was a country, * 1922 † 1991

Italy uses PAL, but it was considered also to use SECAM (B/G) and actually the first color broadcast were in NTSC on NTSC channel 6 using RCA cameras and transmitter, modified to run on 50 Hz vertical sync. In the TV museum in Turin sometimes there’s on display the camera they used at the time. And if you look on the roofs you can still see sometimes a VHF antenna for NTSC channel 6 renamed as channel C. An the end Italy settled to use PAL, but for a long time the regular broadcasts were in black and white, but there were test broadcasts either in PAL or SECAM with Telefunken and Thomson lobbying for their system.

Black and white signals could still be considered composite signals – a combination of video, blanking and sync.

Hence: CVBS https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CVBS

Having lived through the times where PAL and NTSC were the norm, it’s hard to believe they are a distant memory now. It was so hard to increase the resolution or even change to the 16:9 image ratio back then. Then came the digital formats and the advances in resolution and image quality have skyrocketed.

Aside from some retro enthusiasts, you’d say that few would be interested at all in these analogue standards.

Back in the day of transitioning to digital capture of video, it was a nightmare with combing, de-interlacing, wrong order of frames, full frame vs half frame movies, 3:2 pull down, conversion between NTSC and PAL and back, translation of levels (ie 0-255 vs 20-230 or so, getting either an blown out or washed out image, skipped frames etc. composite, s-vhs, component, RGB, beta cam, pre-blacking of video tapes, long play, dot crawl, letter box, teletext, subtitles, safe zones, overscan.

Oh France, what joy in the world of analog TV receiver development. It would the also mentioned the beauty of the positive L modulation of the luminance signal vs negative modulated PAL-B/G in other EU countries.

For the young guys here, in the luminance signal has the line sync, which is blacker than black. If then on the HF side the signal is negative inverted, you have a nice constant level with every sync impulse, which was then the highest level in the HF signal. Which could be used as reference for the gain of your HF input stage.

And then France came and used positive modulation. Which means the highest level on the HF side gets dependent on your luminance signal (brighter picture -> higher level) and then all your HF amplifiers wants to follow this.

Even in the 2010’s it was the high art of TV receiver design to get a reasonable reception of a France TV signal…

Digital TV is soooo boring. :)

AM audio too, when all the other contemporary systems used FM. It did at least get NICAM stereo later – at the expensive of video bandwidth.

“The French copy no-one, and no-one copies the French.”

Nobody copies the the French. Especially their 819 line system. As a schoolboy on a daytrip to Bolougne I saw a TV with a 625/819 switch in the front window of a shop. Alas it was off so I’ve no idea if it actually looked any better.

Well, there was an upside to SECAM. It was such a PITA to encode a signal from video games, that the SCART standard had to be developed. That then made connecting games consoles, VCRs and early digital tuners much easier.

+1

The French Atari 2600 had an 8 color limit because of SECAM.

It basically used a Pong era graphics chip (with SECAM support) to encode grays into color.

To make this works, the console was hard-wired to tell the game that it should use its setting meant for playing on b/w TV.

The French NES used a PAL to RGB transcoder chip, to make a French RGB-capable TV happy.

That’s how I vaguely remember it.

I don’t think the synchronized data “packets” are referred to as “pixels” in either format. It’s analog, so there’s no such quantization. It’s a timing thing meant to energize a standardized grid of phosphors by a scanning charged beam of electrons; limited only by the frequency of the sample rate of the source encoding and subsequent transmission.

I have always heard each individual “pixel”, as it were, in the grid referred to as phosphors.

Anyway early Pal receivers had no delay line at all. The human eye (and brain) did the job of mixing (say) the odd too blue linees with the even too yellow ones. Unless extreme phase errors it was good enough, at least from the normal viewing distance.

Today we if have some genius who swear they can spot the difference between a 4K and a 8K display from 5 meters :)

How large is the display?

4K on a 100″ set is roughly 45 pixels per inch, which isn’t very much. The average person wouldn’t notice, while someone who’s far-sighted might see individual pixels.

45 ppi matters if you are @1 m from 5the display not from 5m or so.

Displays are meant to be seen from a distance like 6 – 7h for 16/9 or 5 – 6h for 4/3.

Size is then not relevant, and fhd is more than enough.

Obviusy almost always a 8k display is newer than a 4k or a fhd, so likely the former comes with better contrast/gamut/whatver, that‘s what people notice.

The resolution is just placebo effect

If the pixel size is close to your eye’s angular resolution, you start seeing the screen-door effect and artifacts caused by the grid. If you can just about see individual pixels, you’re too close to the screen.

The next point is actual image detail. Since an individual pixel or a line on the screen is not enough by itself to represent an arbitrary “line” or “point” of detail in the image, we have the Kell factor: how much you have to blur the image to avoid moire-like effects on screen.

What that means, the 45 PPI screen can represent about 30 points of actual detail per inch, which means a point size of about 0.84 mm. The very best sighted people can see details down to about 0.7 mm at 5 meters distance, so the 100″ 4K screen is right at the limits of where someone could notice that the image is slightly blurry, compared to an 8K screen. That is what’s physically possible.

Yet another factor is image compression, which loses far more detail than the physics and mechanics of rendering pictures on the screen. While the physical limits of 4K vs. 8K is rather academic, this is what even the average person would notice. Of course if you have twice the resolution, your compression macro blocks become a quarter the size and the blurriness and artifacts become less noticeable.

Image compression is also why FullHD typically looks just as good as 4K or 8K. The allocated bandwidth in transmission is roughly the same, because bandwidth costs money, so adding more pixels isn’t giving you a better picture – it’s just a marketing trick. I would rather have 1080p with no artifacts than 8K full of compression artifacts and motion prediction stutter all over the place.

Sure but still you normally use a TV to watch movies not to read ebooks. The eventual pixel slight blurry is, practically, a non existing problem.

I used a 800×600 22″ TV, from the early 2000s, until a couple of years ago, aside the aspect ratio it was (and still is) a marvel in colour rendition, contrast, fast response, lack of artifacts and so on.

I replaced it just because I got a bigger iron for free, but frankly the new thing is not on par with it.

Of course it wouldn’t show them, because it has to scale the image down even from 720p and the artifacts disappear in the blur of the anti-alias filter.

I grew up in a house with a black and white TV only, but I could generally tell the difference between broadcasts filmed in black and white and those filmed in colour. I couldn”t say what the difference was, even then (we’re talking four decades ago), but there was a difference that was clear enough to me… maybe it was that the range of grey shades on the screen was broader, or the picture was slightly sharper?

Back in the day I recall an Australian electronics magazine having

NTSC = Never Twice Same Color

PAL = Peace At Last

I know it as:

NTSC = Never Twice Same Color

SECAM = System Entirely Contrary to American Method (French)

PAL = Perfection At Last

Another funny one I’ve heard is SECAM = Several Extra Colors A Minute (referring to SECAM color fire)

PAL = Pay the Additional Luxury

Don’t forget Brazil!

Brazil used PAL encoding with NTSC frame rate and resolution. I’ve never been to Brazil but I’ve seen equipment set up for their video standard and it was beautiful, combining the lack of flicker inherent to 60(ish)hz and the lack of weird color artifacts inherent to PAL

I think there were about a half dozen Umatic decks for rent in all of NYC.

BTW, Carole Hersee and Bubbles are missing from your test chart.

Multisystem TVs had them all – NTSC both with 3.58 and 4.43 color carriers, PAL and SECAM. But PAL also didn’t need the color burst signal (which an NTSC tv uses to detect color). The color burst synchronized the PLL for color decoding. That’s why NTSC moved from 60 fields per second to 59.94 – to accomodate the time for the color burst. PAL stayed at 50 fields per second.

PAL did need the colourburst – the PLL still needed to be synchronised, even if the phase was less critical; but also, the colourburst alternated from 135° to 225° every line, in sync with whether the V carrier was inverted or not (cos+sin and cos-sin, basically)

I get that there’s a limit to how much you want to elaborate in an article like this, but an “explanation” that includes lines like “To successfully I-Q demodulate the sub-carrier it’s necessary to have a phase synchronised crystal oscillator” doesn’t feel like much of an explanation to little ol’ me. I feel like it’s written for people who already know all of it.

“the difference between the red and the luminance, or R-Y, and the blue and the luminance, or B-Y. These are then phase modulated as I-Q vectors”

It’s not obvious to everyone what an I-Q vector is, though it sounds pretty intelligent ;-) !.

Let’s think: the subcarrier is the higher-frequency signal which itself has a phase and amplitude. I imagine that a decoder is less sensitive to phase than amplitude, so is B-Y assigned to the phase and R-Y the amplitude?