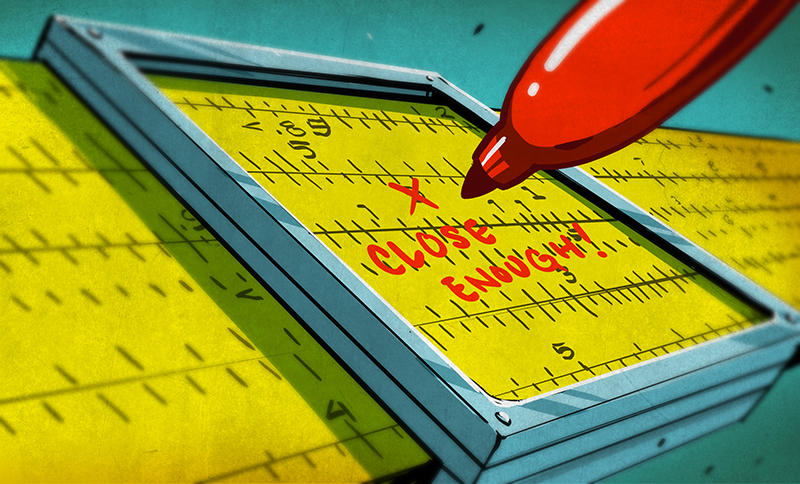

We miss the slide rule. It isn’t so much that we liked getting an inexact answer using a physical moving object. But to successfully use a slide rule, you need to be able to roughly estimate the order of magnitude of your result. The slide rule’s computation of 2.2 divided by 8 is the same as it is for 22/8 or 220/0.08. You have to interpret the answer based on your sense of where the true answer lies. If you’ve ever had some kid at a fast food place enter the wrong numbers into a register and then hand you a ridiculous amount of change, you know what we mean.

Recent press reports highlighted a paper from Nvidia that claimed a data center consuming a gigawatt of power could require half a million tons of copper. If you aren’t an expert on datacenter power distribution and copper, you could take that number at face value. But as [Adam Button] reports, you should probably be suspicious of this number. It is almost certainly a typo. We wouldn’t be surprised if you click on the link and find it fixed, but it caused a big news splash before anyone noticed.

Thought Process

Best estimates of the total copper on the entire planet are about 6.3 billion metric tons. We’ve actually only found a fraction of that and mined even less. Of the 700 million metric tons of copper we actually have in circulation, there is a demand for about 28 million tons a year (some of which is met with recycling, so even less new copper is produced annually).

Simple math tells us that a single data center could, in a year, consume 1.7% of the global copper output. While that could be true, it seems suspicious on its face.

Digging further in, you’ll find the paper mentions 200kg per megawatt. So a gigawatt should be 200,000kg, which is, actually, only 200 metric tons. That’s a far cry from 500,000 tons. We suspect they were rounding up from the 440,000 pounds in 200 metric tons to “up to a half a million pounds,” and then flipped pounds to tons.

Glass Houses

We get it. We are infamous for making typos. It is inevitable with any sort of writing at scale and on a tight schedule. After all, the Lincoln Memorial has a typo set in stone, and Webster’s dictionary misprinted an editor’s note that “D or d” could stand for density, and coined a new word: dord.

So we aren’t here to shame Nvidia. People in glass houses, and all that. But it is amazing that so much of the press took the numbers without any critical thinking about whether they made sense.

Innumeracy

We’ve noticed many people glaze over numbers and take them at face value. The same goes for charts. We once saw a chart that was basically a straight line except for one point, which was way out of line. No one bothered to ask for a long time. Finally, someone spoke up and asked. Turns out it was a major issue, but no one wanted to be the one to ask “the dumb question.”

You don’t have to look far to find examples of innumeracy: a phrase coined by [Douglas Hofstadter] and made famous by [John Allen Paulos]. One of our favorites is when a hamburger chain rolled out a “1/3 pound hamburger,” which flopped because customers thought that since three is less than four, they were getting more meat with a “1/4 pound hamburger” at the competitor’s restaurant.

This is all part of the same issue. If you are an electronics or computer person, you probably have a good command of math. You may just not realize how much better your math is than the average person’s.

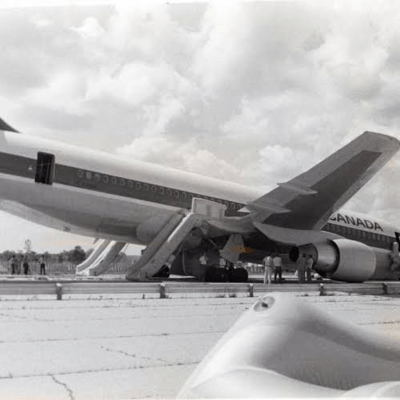

Gimli Glider

Even so, people who should know better still make mistakes with units and scale. NASA has had at least one famous case of unit issues losing an unmanned probe. In another famous incident, an Air Canada flight ran out of fuel in 1983. Why?

The plane’s fuel sensors were inoperative, so the ground crew manually checked the fuel load with a dipstick. The dipstick read in centimeters. The navigation computer expected fuel to be in kg. Unfortunately, the fuel’s datasheet posted density in pounds/liter. This incorrect conversion happened twice.

Unsurprisingly, the plane was out of fuel and had to glide to an emergency landing on a racetrack that had once been a Royal Canadian Air Force training base. Luckily, Captain Pearson was an experienced glider pilot. With reduced control and few instruments, the Captain brought the 767 down as if it were a huge glider with 61 people onboard. Although the landing gear collapsed and caused some damage, no one on the plane or the ground were seriously hurt.

What’s the Answer?

Sadly, math answers are much easier to get than social answers. Kids routinely complain that they’ll never need math once they leave school. (OK, not kids like we were, but normal kids.) But we all know that is simply not true. Even if your job doesn’t directly involve math, understanding your own finances, making decisions about purchases, or even evaluating political positions often requires that you can see through math nonsense, both intentional and unintentional.

[Antoine de Saint-Exupéry] was a French author, and his 1948 book Citadelle has an interesting passage that may hold part of the answer. If you translate the French directly, it is a bit wordy, but the quote is commonly paraphrased: “If you want to build a ship, don’t herd people together to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.”

We learned math because we understood it was the key to building radios, or rockets, or computer games, or whatever it was that you longed to build. We need to teach kids math in a way that makes them anxious to learn the math that will enable their dreams.

How do we do that? We don’t know. Great teachers help. Inspiring technology like moon landings helps. What do you think? Tell us in the comments. Now with 285% more comment goodness. Honest.

We still think slide rules made you better at math. Just like not having GPS made you better at navigation.

When I started my engineering degree in 1980, slide rules were already a curiosity. And curious I was. I eventually got my mitts on one and played with it. Understanding the fundamental logarithmic nature of it not only made me better at math, but also made me want to know more math.

And how have I never before encountered that quote from Mr. Petit Prince?

It’s amazing that this is still amazing to anyone who has spent multiple decades interacting with people on at least a semi-daily basis, though one of the common biases people have is the polite assumption that other people understand the conversation you’re having.

What’s interesting is that parts of the problem are not as simple as “innumeracy”. For example, if you ask which is larger, 1/3 or 1/4, what you’re really doing in words is asking “Which is larger, a third or a quarter?” First you have to parse the words out to mean fractional numbers. If the person is not primed for a math quiz and you spring the question on them, they may simply trip over it and answer nonsense. It’s like the trick of suddenly saying “The idiot says what?”. Ha ha, gotcha. Fast thinking vs. slow thinking mode. Your brain gets a cache miss and has to wait for RAM.

When people see an expression like “a quarter pounder”, that’s an arbitrary label. One doesn’t usually mind what it actually means. It’s a hamburger. If the usual choice is between a Big Mac and a Quarter Pounder, those words don’t mean numbers. It isn’t about math.

If you were asking the question as “Which is larger, a third or a fourth?”, the answer might be different. Now the brain isn’t instantly jumping to food, or the physical sizes of coins.

On a related note, people are generally not so much rational thinkers as they are associative and heuristic thinkers. That is the default mode. If that fails, then comes analytical thinking.

“Fast thinking vs. slow thinking mode. Your brain gets a cache miss and has to wait for RAM.”

LOL

One interesting thing I’ve learned from my travels is that different cultures intrinsically think and talk about math in different ways. I saw this while working in China.

From what I could gather, as someone who does not speak Chinese, the language has a subtly different way of dealing with numbers, in a way that simplifies the mental gymnastics involved.

There, the language for this question would not be “which is bigger one third or one quarter?”, it would more literally translate into “which is bigger, one out of three parts or one out of four parts?”

Likewise, the number 1592 would not be spoken as “fifteen-ninety-two”, it would be spoken much more explicitly as “one thousand, five hundred, nine tens, and two”.

It’s subtle, but it seems to me that it embodies more of the actual meaning of numbers, and less of then as logical tokens.

Depends on context: if that’s a phone extension or a street address it’s going to be said “one, five, nine, two” and of course the Chinese have two words for two. Ah the mysterious east.

Can’t speak for the Chinese but Japanese street addresses take a bit of getting used to. The only way I can describe them is a location on a tree where successive numbers describe cross streets or passages, houses, locations in houses and so on. It “kinda, sorta” makes sense but it takes a lot of getting used to.

(FWIW — Moroccan souks (markets) are a “maze of twisty passages, all alike” but fortunately every nook and cranny has electricity and so electricity meters. The addresses may be beyond comprehension but you can navigate by the meter numbers!)

That’s American English, not English.

As a Brit, I would at least say fifteen hundred and ninety two (if I’m feeling lazy). More usually, I would say one thousand five hundred and ninety two. I would never say fifteen ninety two, even after 6 years in the States.

For a year? I’m pretty sure you would confuse the hell out of people if you were referring to 1592 and said the year 1 thousand 500 and 92 and you weren’t doing some dramatic voice with it.

There are many languages that don’t say “eleven”, they say an equivalent of “first of the next decade”, or when they say “a third”, they say “one part of three”. They are much more explicit, because they are agglutinative languages – they form words out of sub-parts with distinct meaning rather than having a separate label per idea (analytic languages).

What that means, each word almost explains itself. “Eleven” does not explain itself, you have to know what it means, whereas the Estonian “üksteist” (one + of the second) does.

Though for some historical reason, the counting words after the second decade usually continue in the form of “twenty one, twenty two…”

English retains the same feature, with “-teen” denoting “ten”, so thirteen is “three-ten”, but this is inconsistent. Teen has become to mean a number between 13-19 in particular, while the Estonian “-teist” is a general adjective, such as “poolteist” for one and a half (half + of the second).

The context defines what the “of the second” means – it’s generally adding the base unit, whether that’s 1 or 10.

Onety, Onetyone, Onetytwo…. assuming that the number up to 100 are not broken already.

One Hundred

One Thousand

now we need to go for:

One Teen, One Teen One, One Teen Two…

The words “twelve” and “eleven” originally come from old Germanic and basically mean “one/two left over”.

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Reconstruction:Proto-Germanic/-lif

So it’s counting eight, nine, ten, one more, two more….

Actually, it’s not. It literally means “4 oz. hamburger patty net weight before cooking”.

If they advertise their 3 oz. net weight before cooking hamburger as a quarter pounder, someone is going to sue them over it.

Yes, that is the literal meaning, but not what I meant with that.

It’s a label that refers to a particular thing, such as a particular burger available in a restaurant. We don’t, or at least many don’t, think of it in terms of the actual weight but in terms of the hamburger. We don’t eat a “hamburger with a 4 oz. patty”, we eat a Quarter Pounder. For all we care, it could be named “Royale with Cheese”.

The fact that someone might sue over mislabeling if the patty was actually 3 oz. is not relevant to the point.

BTW. the quarter pounder is actually a four and a quarter oz. patty. They changed it, possibly because somebody sued over the ambiguity.

Totally irrelevant what the actual weight is, as its not in metric. In the majority of places in the world, the name is associated with the product, not the weight of this product, which, incidentally, in my neck of the woods lists as 113 grams for the patty made of polish handcut pieces of beef from the frontal regions of the animal yadda yadda yadda.

Regarding a quarter pounder….the half gallon tubs of ice cream have been 3 pints for decades now but they’re still half gallons. To differentiate from the other two sizes, pint and budget bucket.

The street smart person doesn’t look at the name, they look at the burger they’re served.

The case with the 1/3 vs. 1/4 pound burger may well have been people comparing burgers to burgers and concluding that the Quarter Pounder is actually bigger due to what else they put in between the buns, while the marketing people put the blame on people being dumb to cover their own asses. After all, reality is what gets reported to management.

“Street smart”? “The badass pimp daddy-O doesn’t look at the name” or refer to themselves as “street smart”.

Usually, people who refer to themselves as smart or intelligent, aren’t.

So how much copper would a big datacenter require? I don’t even know where to begin. Are we talking 3.3, 5, 12 volts where currents are high (per watt), or 220 volts and higher where currents would be much lower? Are you including distribution lines, transformers, and generators to get the power to the data center? What percentage of those lines would actually be aluminum instead? This would take a lot of fuzzy math to calculate.

Ok. How many blades of grass on a (US metaphor for global war football, not FIFA football) football field?

Yes, a lot of fuzzy math. but easy to be within an order of magnitude.

See Jon Bentley, Programming_Pearls, “The Back of the Envelope” (Column 7 in the second book edition. I don’t recall the CACM issue it was originally in)

An “order of magnitude” is sometimes defined as 0.3 to 3 times some arbitrary baseline. If the real answer and your answer fit within one order of magnitude of that baseline, your answer may still be 10x off in the worst case.

This is actually “round log(number) to the nearest integer”. It’s not quite 3/0.3. Astronomy uses the term “dex” for a factor of 10, so order of magnitude is rounding to the nearest dex.

An older reference is “Fermi estimation”, though I’m sure the technique goes back even further still; just that there wasn’t as much science in general to do, quantitatively at that, in past history. I’m sure Gauss did it when calculating orbital mechanics or something, but we can’t name everything after Gauss (or Euler), haha.

Usually much higher voltages – 480V and up for that kind of industrial setting.

And if you want to save on the transformers, you run it at 400 Hz like the airplane stuff. Smaller cores and windings.

the linked article (with the now fixed 200,000kg of copper so there’s your answer) has 56V DC listed as being used, so there’s the detail you asked for about the voltage

Let’s reduce the power consumption of data centers by 500% by using beautiful green coal.

Well, there’s your perfect example of innumeracy right there.

Let’s also build them Titanic-sized coal burners heating Titanic-sized water boilers so the Titanic-grade steam would be churning Titanic-sized power generators belching Titanic-sized clouds of cinders and ashes.

Greenpeas (pun intended) should be all over this yelling “bad bad wolf!” but they won’t be. They are incapable of anything larger than pretending they make a difference (challenge – Greenpeas sure should be able to stop ongoing worldwide wars, source of the absolute worst kind of pollution there is, I mean, all they have to do is wind up one of their hot air generators and let it loose).

You aced the test !

Thank you for your attention to this matter !

People ‘longing for the sea’ suddenly become competent ship builders and sailors?

I don’t think so.

Teach generally competent people to ‘long for the sea’ perhaps, but that’s maybe 1 in 5.

Otherwise you’re just creating customers for GD cruise ships,

Perhaps future Darwin award winners.

The fact is the Innumerate are just stupid and/or lazy.

You can’t fix stupid and to ‘fix’ lazy you’ve got to do it early.

Idiocracy is a documentary.

You can fix how people are raised and taught so badly they think they’re inherently, congenitally, bad at things and they shouldn’t try. At least in theory.

Most people lose the math thread in GD grade school.

After that they try to pass w memorize and regurgitate.

That’s how people ‘learn helplessness’.

Their only hope is to go all the way back to where they lost it.

Sometimes that’s GD counting.

It’s always years before it became obvious to them that ‘math is hopeless’.

Ego won’t let them go back to 2nd grade.

So ego says ‘math is useless’!

Only nerds even take calcuseless!

Like that’s even an option for them.

All you can say is: ‘Better luck w math next reincarnation.’

Same as they say about our ‘fashion sense’ and dancing.

After 25+ years of fixing errors I’ve learned that every time I hear “there’s something with your math” it means “our data sucks, but we don’t know where or why or how”. I usually run few SQLs here and there and spot some kind of calamity that was introduced for unclear reasons that caused the math to go bad. Since I am not a BA, bussines bananalist, nor am I am so-called “manager”, so I am almost never “in the loop” where I NEED to be – to know those things in advance BEFORE they make math looking bad.

IMHO, It is not math in general, it is literally those who don’t know why they are using it who say “math is useless”. Math powers world economies just fine, directly, indirectly, no matter. Those who don’t know how to use it are the ones cancelling all the advantages it offers – and whining about it, “it is too advanced … too complicated … “, basically they are too lazy to open a textbook and self-edumacate (mis-spelking Nintended :-]).

Spoiler – I do have relatives with Masters in Math. I call them M&Ms, and they appreciate the humor – because that’s how it works, even M&Ms don’t take themselves too seriously, it is those unwilling to do their proper homework who do. There is good M-word for those too lazy to do their homework, but I’ll spare their overinflated egos from being deflated.

There was a nice SF novel, I just forgot the name:

A guy wakes up in a locked room. He seems to have lost his long-term memory.

After some time he finds out that he measures household distances/weights in inches/feet/ounces, but technical ones in ISO. He is also able to convert them on the fly, finding that he’s not using imperial but American Survey units.

His conclusions: I must have grown up in the U.S., and I’m a technician or scientist.

It would be so easy if we could just split at this line:

Use cultural units for household or daily measures, but please use ISO when going technical or international. Tell me about your chocolate bars in ounces, I can convert that. But stop asking for 15/32 inch drilled holes (unless it’s archery).

This message will self-destruct in 2345/13 kobo-Ticks.

The novel is Project Hail Mary by Andy Weir. Motion picture to be released in March!

The book was great. I hope they don’t hollyweird this movie up like they do everything else. I am really looking forward to it!

… even if/when they do hollyweird fork, I am truly looking forward to the hillariously bollyweird copycat version of the hollyweird fork : – ]

” stop asking for 15/32 inch drilled holes”

The issue isn’t ‘metric vs customary.’ It’s two different standards groups. It’s ISO vs SAE. “15/32 inch” holes are metric. They’re exactly 11.90625 mm. The spacing isn’t “nice and round” but it’s just a number. Tolerance rounds it out anyway.

There are plenty of mixed metric/customary standards out there. All the rack standards are mixed. All the card dimensions are metric, but the spacings are HP which are 0.2″ (plus, obviously, the whole 19 inch thing). Doesn’t cause an issue.

And the fact that we have two standards groups isn’t surprising considering what was going on in the early 20th century.

““15/32 inch” holes are metric. They’re exactly 11.90625 mm.”

Can you please explain me this? As a European I have never encountered none of this numbers. Not on my drill bits nor in any discussion with fellow technicians/engineers. Although I do admit that I rarely do drilling.

An inch is exactly 25.4 mm. Exactly. That’s its definition. All customary units are metric defined and have been for forever.

The idea that the metric system means we all use one set of units is just not right. We all use one standard. And that includes customary units. The tooling issue is separate. You have the same issue with Philips and JIS screws.

Given they are both metrics, maybe SI instead of “metric” would have more clarity.

An 11.90625 mm drill is metric, and it would still piss people off.

It’s a standards issue. If you made drills spaced in circumference spacing instead of diameter it’d be just as logical and just as much of a pain.

We had “practical” and “scientific” electrical units for a long time, too, before scientists realized they were never gonna convince the electrical types to change and bowed to the pressure (okay not really but… actually kinda close).

Meaningless digits are meaningless.

Asking someone competent for a 11.90625 mm drill would get you a funny look.

Nothing is impossible.

That’s going to be one expensive drill bit w a short life, reflecting badly on the ethics of the seller.

They promise it was too spec when it left their hands.

You didn’t take it out of the nitrogen filled holder to measure it?

What temperature was the measuring tool at?

That said, that reflects common shorthand for measurements without tolerance.

‘11.90625 mm’ is an unreasonably tight tolerance.

+/- 0.000005 mm

Good luck.

“Asking someone competent for a 11.90625 mm drill would get you a funny look.”

Yes! Because the ISO standard uses stuff in tenths or hundredths of a mm diameter. They didn’t have to. AWG isn’t in tenths or hundredths of an inch, it’s logarithmically stepped.

“‘11.90625 mm’ is an unreasonably tight tolerance.

+/- 0.000005 mm”

Bzzt. Wrong. Digits do not imply tolerance. They imply the central value. Precision vs accuracy. You can have 11.90625 mm +/- 0.5 mm. OK, sure, that’s extreme, but I can get 5% resistors with a nominal “digit specification” better than 5%.

But more importantly – you don’t know where that spec comes from. 11.90625 mm is 1143/96ths. So maybe they’re spec’ing drills in 96ths of a mm, which is 0.01 mm precision. Or maybe, like I said, they’re spec’ing the circumference of the drill (which isn’t what we do, but is a completely reasonable choice), and you’re picking up pi.

Standards and specifications are arbitrary. The issue that frustrates people is when there are more than one dominant standard. And that’s just life for a world that was fractured by war in the early 20th century.

In the 1960s, the image of a high school nerd was a kid walking to class wearing his K&E slide rule in a leather scabbard hanging from his belt (u-mercari-images.mercdn.net/photos/m32208348541_1.jpg)

Hopefully, that kid grew up into an engineer in the 70’s, realized that a technology revolution was at hand, and bought a few hundred dollars of Microsoft stock at 14 cents.

Wouldn’t have been possible but he mos’def bought a bitchin’ HP calculator which went in a similar zippable scabbard.

Believe it or not, I was one of those nerds with a HP41C in a nice leather holster on a belt loop. When I walked into a room once, one guy (seriously) asked if I was carrying. Most people there/then kept them in their briefcases (kid you not).

My high school classmates didn’t have briefcases, don’t try to teach your grandmother what was on The Brady Bunch.

Yeah, not high school. Business meetings. And nobody knew about any Brady Bunch there. Not that far from Elon Musk’s high school though, actually, but he would have been a pre-teen then.

So in South Africa then. Unbelievable.

Fine supple black leather with Velcro. No zippers.

Open top, quick draw, calc slinger style.

Slight friction fit, silk lined.

If I fell, I was like a cameraman, cat like body twists to protect the calculator.

When I was a kid in the late 80’s, I was the odd ball. I not only carried – and used – a slide rule, my rule of choice was a CIRCULAR slide rule. I still have that to this day!

I’ve been on that runway; it’s still used for racing, but the runway has been destroyed such that it isn’t useful in an equivalent emergency.

I all too often see graphs in the news media and on the WWW with no explanation of what the numbers on the axes mean.

“We miss the slide rule.”

No. No we don’t. And we don’t miss the dictionary sized book of logarithms we used to have to carry with it. For that matter we don’t miss carrying other books either (usually ~30 lbs of them in my undergrad days) through the snow and ice.

Forget calculators, when I retired four decades later, my engineering students were carrying a linked laptop and a phone as well as classes that were sent to them rather than the reverse so the snow and ice (as well as their location) was irrelevant.

If it makes anyone feel any better, they were still getting things wrong by orders of magnitude on occasion. It will be interesting to see if “AI” incorporates that as a human-necessary feature.

Why would you need a book of logarithms if you have a slide rule? Are you making that up?

Slide rules typically produce only one or two digits of accuracy. The books typically used 4-6 (or more) depending on the table. I suspect they also had more tables than a typical slide rule had scales. So you would use them for the same reason you would use a pencil/paper/slide rule instead of just rounding off to something easy enough to do mentally.

A book of logs?

How many digits are they carrying around?

Most likely a book of steam tables, w logs and a few other useful tables in appendixes.

I remember those as appendixes to almost all serious textbooks, printed in the absolute tiniest technical possible font that’s still humanly readable (with glasses). Last book I’ve opened in, I think, 1986 had maybe a dozen pages with these (also had some square roots, etc). Not a lot. Most were up to 6th digit, some were 4th digits accuracy.

Makes me think it is rather trivial making them into LUTs – after all, that’s how those $12 “scientific calculators” work – by looking up values in LUTs. Databases of LUTs they truly are, cheap calculators.

“after all, that’s how those $12 “scientific calculators” work”

Not exactly. In most of those devices what happens is that you have a lookup table for initial values that gets you ‘close’ and then there’s a cleanup/interpolation step which gets you the final result.

It’s silly to store a full lookup table, because you still do have a processor that can do math.

I don’t miss them, because I still use them. I have an E6B in my flight bag (basically a circular slide rule) and also keep one on my sailboat. I have several watches with slide rule bezel rings. They are a backup when the electronics fail. Using them is a skill; you need to practice or you loose it.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry he had quite a number of excellent books that should be read by high school kids in any country, really. Not merely for the joy of reading “foreign literature”, but for the joy of finding gems of thoughts the they can relate to, and there are plenty within.

BTW, might as well mention “Flight to Arras”. It may sound boring read, and at times it really is, but it is excellent book to persevere through, and doing so puts proper context to the only book really remembered in the US, “Le Petit Prince”, which is usually waved of as some kind of little kids’ fantasy book of no particular/good merit.

Also, “Wartime Writings”, however dry, is quite good read for another reason – it has excellent observations usually omitted from the official news/propaganda. This was before internet and everyone owning a cell phone one can take recordings with, so comes quite close to that.

Flight to Arras was my favourite, and I’ve been to the battlefields around Arras to see the ground over which he flew in 1940. Sadly he was lost on a reconnaissance mission in 1944 over France. His adage on longing for the immensity of the sea/air quoted in the article certainly applied to the Wright brothers and many of the early pioneers who used applied science and engineering to develop the first aircraft.

I think NASA found the answer after losing Mars Climate Orbiter: Mandate the use of SI units.

My understanding is that there have been no incidents since the loss of Mars Climate Orbiter regarding measurement units.

Yeah, no. I can’t stand discussion about MCO because it’s always “LOL english/metric” and that’s not the problem in the slightest.

First off, NASA doesn’t actually mandate SI units, because stuff like “kilometers/hour” is not SI, since ‘hour’ isn’t an SI unit: it’s a non-SI unit accepted for use with SI. This isn’t a pedantic correction because “km/h” and “m/s” are within the same order of magnitude of each other as “cm/s” and “in/s”. You have The. Same. Problem. even though you’re nominally using “metric-y units” or something.

So you already have the problem where someone can provide “metric-y” units in something ‘close but not quite.’ So saying ‘everyone use this system of units and we’ll all be good’ just doesn’t work. At all. And no, “metric time” doesn’t solve the problem either because you also have volume units vs mass units which can do the same thing.

Second off, Lockheed was already supposed to be providing measurements in newton-seconds. The mandate was already there! It was in the contract! So why doesn’t NASA say “hey not our problem, this was Lockheed’s problem”?

Because the issue wasn’t units. The issue was lack of preflight checks. You don’t just drive over to the Lockheed Store, grab a propulsion unit off the shelf and stick it on the rocket the day before launch. What if you misunderstood the binary format that Lockheed was providing? Same issue! Everything scales by a factor of 2, or 4, etc.?

The Mars Climate Orbiter failures are way, way past units. They burned those engines multiple times on the way to Mars. Every one of them was off in terms of how much they actually affected the orbit. Every. One. They ignored it. It was a factor of ~4, but the burns were small that the error didn’t seem important. Like, “I burned for 4 seconds” when the model thought it should’ve burned for 1 second.

And, in fact, there were people on the team who did see this. There was a call to do a trajectory correction before insertion. This was denied because it wasn’t filed properly.

TL;DR?

The units weren’t the problem. Systems integration was the problem.

Innumeracy is so rampant, man. it’s hard to even be honest with people when you know that no matter what numbers you use it will be misunderstood.

Try giving a cashier a $20 dollar bill, a $1 bill, a quarter and three pennies when your bill is $16.28 and you want a single $5 bill in change. The confusion is it’s own entertainment.

oh man i learned not to do that more than a decade ago, when someone used the calculator on their personal iphone to resolve the crisis

Tellers are not paid to think, they are paid to do. Their magnificent cashier apparatuses supposed to think for them, while they are doing their jobs.

I’d approach their manager with the same request. Some managers know what addition is, while others may know how to use it, whereas others may know how to reliably do both, add and subtract, so one out of three managers can work as one third of a cashier. Chances of hitting one manager that knows both are higher when there is some kind of shiny event attracting their attention, say, someone showing the newly acquired engagement ring (such things tend to stretch for hours at a time).

You can enter the amount of cash you receive in the cash register and it tells you how much to give in return. Remember: tell the customer the amount and ask for cash or card, or wait for the customer to take out their preferred method of payment so you can see it before hitting “cash”, so you can actually enter the number – otherwise you have to do tricks to correct it.

The problem: the teller does not know how to use the cash register and doesn’t bother with the procedure, so they enter the amounts and hit “cash” on autopilot. The till opens and then they take the money from the customer.

Now the register has already printed the receipt and they’d have to start over, so they panic, forget whatever little they do remember, and start doing mental arithmetic in a state of confusion.

It never works.

Yep, and since they cannot backout the transaction and start another one, this is the prime case of what’s rightly called “technological idiocy”, unrelated to humans, btw, technology that fails to fail safely, ie, backout and re-try with different parameters.

The term is as old as the term “cyber”, btw. I honestly don’t remember who and when used it first, but that anthropomorphism about nails it just right.

There is milder version of “technological idiocy”, “systemic error”, ie, error that’s part of the system, which became so calcified, it that can no longer be changed/upgraded to fix the error.

Most tellers I’ve run across know how to calculate things just fine – I am pretty sure they pay their home bills, also tally up their bank accounts, just they don’t want to bother with extending their 3rd grade math towards customers, and I don’t blame them. If I am paid piddly allowances with which I am kept from diying of starvation, I’d, too, do the same, pretend I am dumb and dumber, and call the manager to do all the thinking they are paid to do instead of me doing their job for them.

In the slide rule days we learned to use scientific notation for just about everything and had the expected magnitude of a problem mentally before we used the slip-stick. I still do that and spot magnitude errors quite often in the news and this age of no proof-reading.

We gray beards who were fortunate to have been forced to utilized slide-rules in high school and then allowed to utilize calculators (wife gifted me an HP-67 !!!) in university are a fortunate generation as accuracy, precision, and significant digits were forced upon us before calculators were available tthat provided 8 to 10 digits of calculation capability with exponents.

I designed and coded an engine monitoring system based on an Arduino Mega ATMEGA2560 many years ago and the owner of the Rotax (installed in an Europa experimental) and I nearly came to fistfights over the OLED display digits for such items as Battery Voltage and Current.

After I gave in and reworked a few lines of code to give him 4 decimal digits, the complaint was that the display was unstable, constantly flickering in the decimal digits. My answer was to create a multidimensional matrix for every analog reading and then average across the matrix with every iteration of loop(). Essentially creating a rolling average every 5 seconds as the loop was timed to execute once per second.

P.I.T.A.

Complete waste of valuable display space.

Modified all analogRead statements to average across Average_Depth as AReadAvg[Y][Average_Depth] where

Y= [0] = WaterTemp_AnalogIn X = [0], [1], [2], [3], [4]

[1] = OilTemp_AnalogIn X = [0], [1], [2], [3], [4]

[2] = OilPres_AnallgIn X = [0], [1], [2], [3], [4]

[3] = FrontCylTemp_AnalogIn X = [0], [1], [2], [3], [4]

[4] = RearCylTemp_AnalogIn X = [0], [1], [2], [3], [4]

[5] = Ampres_AnalogIn X = [0], [1], [2], [3], [4]

[6] = Voltage_AnalogIn X = [0], [1], [2], [3], [4]

[7] = FuelQty_AnalogIn X = [0], [1], [2], [3], [4]

[8] = FuelPres_AnalogIn X = [0], [1], [2], [3], [4]

The simpler solution is to store the value just once and do a weighted average between the previous and the new value on each cycle. In practice, you could take 4x the old value plus 1x the new value, and divide by five, then store back for the next cycle. This nudges the result by a fifth of the difference every cycle.

Your matrix rolling average does the same but using more memory. What you’re doing is just taking the four old values and summing them together with the fifth new value, then dividing by five. The only difference is that your method represents finite integration time, while the weighted average method is “infinite” integration time. It takes about twice as long to converge to the same steady state value with 5-6 digits of precision as a requirement (e.g two plus four decimals), but that’s not unreasonably long.

The problems start if the customer doesn’t understand that this value represents a state that is up to 5-10 seconds old (in your case). If they expect to stomp on the gas pedal and see an instant change, that’s not gonna happen anyways.

Not necessarily. The customer may actually be interested in the long term average down to the given precision. Whether they’ll actually get anything useful out of it is not your call to make.

The array gives a finite impulse response where as the average as the previous sample gives an infinite impulse response. Though probably not noticeable in engine monitoring at that data rate except in a mechanical failure.

When I worked in the electric grid modeling business we had a client utility that paid us a fair chunk of change to add three digits to the standard load forecast file format.

We were very impressed with their forecast accuracy…

Not really, we knew the PHB responsible, their money was green.

I loved the HP 11C that, with its associated HP Basic got me started as a software engineer in the late 70’s. (I also loved using RPN!) My father, a Mechanical and Lighting Engineer at U.C. Berkeley lamented that the student interns he hired in the research lab often failed to have a handle on the expected outcome of a calculation, often leading to significant errors that were off by factors of 10, 100 or more. In his experience it didn’t matter the tool used for the calculation: Brain, Slide Rule, Mechanical Calculator or ultimately, digital calulators.

In the later stages of my own career as a professor of nursing I often saw similar errors by nursing students who “trusted” their calculator when doing dose calculations – just as with engineering, such errors can have devastating outcomes. So, as always, does the result “make sense?”

Of course, one can always fall back on “42” for the ultimate answer to the ultimate question.

“I loved the HP 11C that, with its associated HP Basic got me started as a software engineer…”

I can find no indication or verification that the HP11C came with ‘HP Basic’.

Are you thinking of some other calculator?

I’m not sure how reliable it is but the rumor is that they are already scaling back AI projections.

Let’s hope so since after GPU and RAM and SSD and power we would also get a (even bigger) copper shortage.. it would all become a bit too much.

And yes although it was corrected on the nvdia page it’s still a lot and we still have the whole EV thing too and the increasing of power infrastructure they are doing overall, so there is a competition for copper already.

Meanwhile the real danger of AI is spreading, namely it being used by governments and ‘partners’ against the citizens.

And even in places like they EU where they make various law to limit AI misuse they happily make exceptions for Orwellian stuff, or the members simply ignore the rules. In the EU it’s often required for somebody to start a lawsuit to make them follow the rules (somewhat).

Excuse the superfluous ‘y’ and missing ‘s’

Hi Al (and that is a lower case L, not an upper i)

I agree with a general concern about AI (now with an upper i) for all sorts of reasons, but please can I ask you to encourage the use of this thing called “spell check”, so we don’t have to get distracted by peices of text like I just used.

I have greatly enjoyed the discussion of hamburgers, Saint-Exupéry, calculators, slide rules, and A.I., but I can’t believe that we have gotten this far into the discussion without anyone’s mentioning my favorite innumeracy, something along these lines:

“Our product has five times less problems than our competitor!”

As if you can take “five” and “times” and get “less.” (Never mind that the word should be “fewer.”)

Yep, those (usually unbased and hollow) claims make me cringe.

Because it should “five times when compared with THIS”. Now, where THIS came from, just how reliable it was to start with, and then who calculated the perfect “five times” and why, all HAVE to be mentioned somehow and somewhere. Because if it really was 5.13 times and rounded to just 5, then it is clear and utter rounding error, one of the classical pitfalls, do we go ceil or floor (this was was floored down to 5; had it been ceilied to 6 that would be even worse error).

Then again, those fake claims are usually for the investors, who tend to be certain math-dumb kind who couldn’t tell which is larger, 1/3rd or 1/4th. All they really want is “no less than 20% ROI in 5 years or sooner.”

Never go full Sheldon.

I was one of those nerds in the late ’50s and early ’60s who went around with my slide rule flopping in a leather case at my belt. Estimating was truly important, along with some mental ricks for truing and accuracy. These days I see a totally blank look on peoples faces if I say “logarithm”. The idea of chaining trig functions together for advanced ballistic analysis is surely beyond today’s high schoolers. Pity.

I broke a spark plug because I was using a torque wrench with the wrong units. Quite an expensive repair