If you get a small cut, you might throw a plastic bandage on it to help it heal faster. However, there are fancier options on the horizon, like this advanced AI-powered smart bandage.

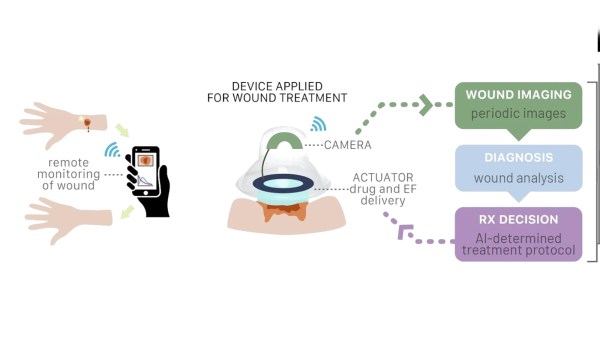

Researchers at UC Santa Cruz have developed a proof-of-concept device called a-Heal, intended for use inside existing commercial bandages for colostomy use. The device is fitted with a small camera, which images the wound site every two hours. The images are then uploaded via a wireless connection, and processed with a machine learning model that has been trained to make suggestions on how to better stimulate the healing process based on the image input. The device can then follow these recommendations, either using electrical stimulation to reduce inflammation in the wound, or supplying fluoxetine to stimulate the growth of healthy tissue. In testing, the device was able to improve the rate of skin coverage over an existing wound compared to a control.

The long-term goal is to apply the technology in a broader sense to help better treat things like chronic or infected wounds that may have difficulty healing. It’s still at an early stage for now, but it could one day be routine for medical treatment to involve the use of small smart devices to gain a better rolling insight on the treatment of wounds. It’s not the first time we’ve explored innovative methods of wound care; we’ve previously looked at how treatments from the past could better inform how we treat in future.