Wireless sensor networks are nothing new to Hackaday, but [Felix]’s wireless PIR sensor node is something else entirely. Rarely do we see something so well put together that’s also so well designed for mass production.

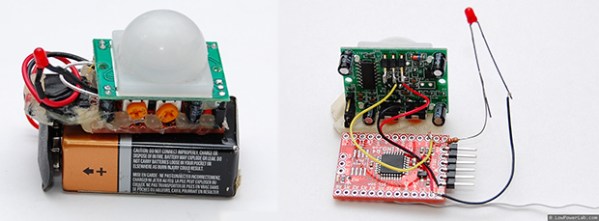

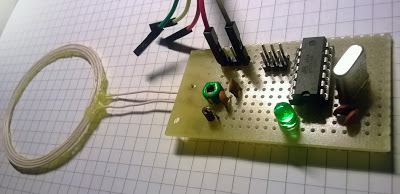

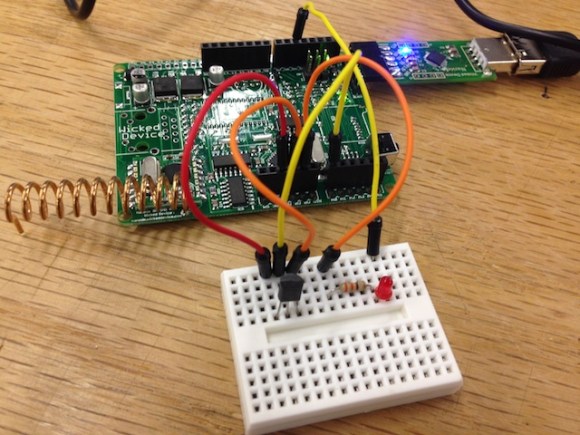

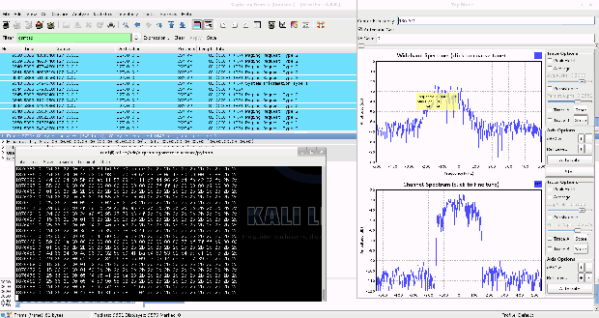

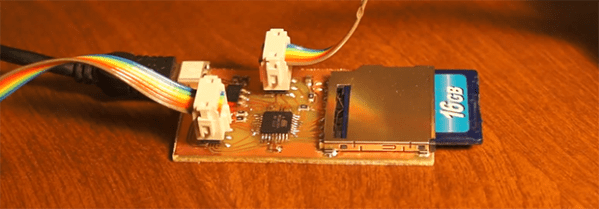

For his sensor, [Felix] is using a Moteino, a very tiny Arduino compatible board with solder pads for an RFM12B and RFM69 radio transceivers. These very inexpensive radios – about $4 each – are able to transmit about half a kilometer at 38.4 kbps, an impressive amount of bandwidth and an exceptional range for a very inexpensive system.

The important bit on this wireless sensor, the PIR sensor, connects with three pins – power, ground, and out. When the PIR sensor sees something it transmits a code the base station where the ‘motion’ alert message is displayed.

The entire device is powered by a 9V battery and stuffed inside a beautiful acrylic case. With everything, each sensor node should cost about $15; very cheap for something that if built by a proper security system company would cost much, much more.