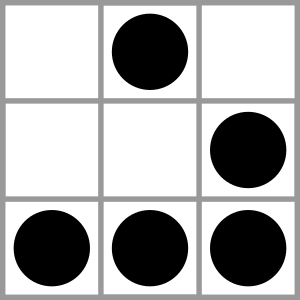

John Conway passed away this week. Even if you don’t know much about mathematics, you will probably know nearly everyone’s favorite cellular automata ruleset: Conway’s “Game of Life”. It’s so much a part of our cultural history, that proto-hacker Eric Scott Raymond suggested using the glider as the hacker emblem.

The idea that a very simple set of rules, applied equally and everywhere, could result in “life” was influential in my growth as a young hacker, and judging from the comments on our article about Conway, I’m not alone. But I won’t lie: I was a kid and thought that it could do much more than make pretty patterns on the screen. I was both right and wrong.

The idea that a very simple set of rules, applied equally and everywhere, could result in “life” was influential in my growth as a young hacker, and judging from the comments on our article about Conway, I’m not alone. But I won’t lie: I was a kid and thought that it could do much more than make pretty patterns on the screen. I was both right and wrong.

Although amazingly complex machines can be built in Conway’s Life, just check out this video for proof, in the end no grand unifying theory of cellular automata has emerged. As a research topic Conway’s chosen field of mathematics, cellular automata is a backwater. It didn’t really go anywhere. Or did it?

Implementing Conway’s Life in BASIC on a Tandy Color Computer was one of the first things that launched me on my geeky path. It ranks with MENACE: the matchbox-based machine learning algorithm from the 1960’s and an introduction to Markov Chains in the form of a random text generator in my young algorithmic life, all of which I incidentally read about in Martin Gardner’s column in “Scientific American”. Conway’s Life, along with some dumb horse-race game, also taught me about bad random-number generators: the screen would populate the same “randomly” every time on the old CoCo.

So maybe Conway didn’t want to be remembered just for his “Life” because it was a bit of a mathematical dead-end. But in terms of its impact on the world, an entire generation of hackers, and my own personal life, it was able to fill up significantly more than a screen full of pixels. Here’s to Conway, his “Life”, and everyone else who is inspiring the next. You’re not just gliders, you’re glider guns!

[Game of Life example shown in this article is John Conway’s Game of Life – 1.0 written in Python by Nick Jarvis and Nick Wayne]

Many readers will be familiar with

Many readers will be familiar with