Noise is all around us, and while acoustic noise is easy to spot using our ears, electronic noise is far harder to quantify even with the right instruments. A spectrum analyzer is the most convenient tool for noise measurements, but also adds noise of its own to whatever signal you’re looking at. [Limpkin] has been working on measuring very small noise signals using a spectrum analyzer, and shared his results in a comprehensive blog post.

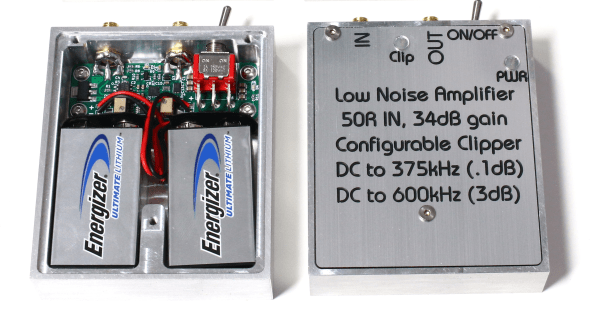

The target he set himself was to measure the noise produced by a 50 Ohm resistor, which is the impedance most commonly seen on the inputs and outputs of RF systems. The formula for Johnson-Nyquist noise power tells us that the expected noise voltage in a one-hertz bandwidth is just 0.9 nanovolts – tiny by any standard, and an order of magnitude smaller than the noise floor of a typical spectrum analyzer. [Limpkin] therefore designed an amplifier and signal buffer to crank up the noise signal by a factor of 100, using ultra-low noise op amps running off a pair of nine-volt batteries.

There was a problem with this circuit, however: any stray DC voltage present at its input would also be amplified to levels that could damage the analyzer’s sensitive input port. To prevent this, [Limpkin] decided to add a clipper circuit to his amplifier. This consists of a pair of comparators that continuously monitor the amplifier’s output voltage and disconnect it through a silicon switch if it goes beyond 200 millivolts. [Limpkin] packaged his circuit in a beautifully-machined case and ran various tests to ensure the clipper worked reliably even in the presence of fast input transients.

With the clipper in place, it was safe to run the planned noise measurements. The end result? About 0.89 nV, just as predicted by theory. Measuring nanovolt-level signals usually requires extremely accurate equipment and lots of tricks to minimize noise. Sometimes though, noise is just what you need to make a radio transmitter. Thanks for the tip, [alfonso32]!