There’s nothing quite like going to a museum and being given a tour by a docent who really knows their way around the exhibits. When that docent has first hand experience in the subject matter, the experience is enhanced even further. So you can imagine our excitement when hacker, maker, and former DEC mainframe memory engineer [Ned Utzig] published a tour of what he calls “Memories of Weird Memories of Computers Past.” [Ned] expertly guides us through each technology, adding flavor and nuance to an already fascinating subject.

The tour begins with early storage media such as IBM punch cards, and then walks us through time to the paper tape, vacuum tubes, and even complex vats of mercury — all used for the sake of storing data either permanently or temporarily.

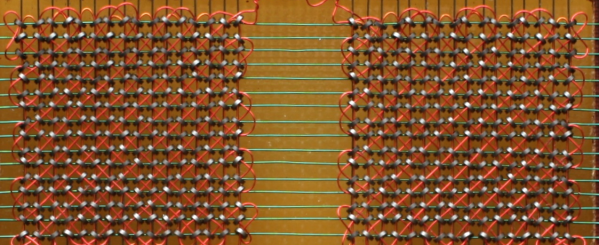

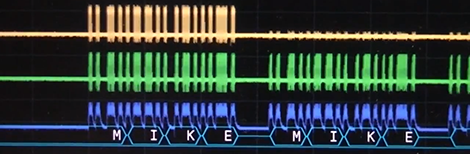

Next in the exhibit is an impressive CRT hack that isn’t unlike modern DRAM. The tour continues on to ferrite core memory such as that used on mainframes, minicomputers, and even the Apollo Guidance Computer. Each type is examined for its strengths and weaknesses and its place in computing history.

We really appreciated the imaginative question posed toward the end of the article. We won’t give it away here- it’s worth it to go give The Mad Ned Memo a read.

Is obsolete technology your cup of tea? Perhaps an Arduino based experiment with core memory will scratch the itch, or maybe storing data in thin air will bring back memories of computers gone by.