This is the first we’ve heard of Parametric Press — a digital magazine with some deep dives into a variety of subjects (such as particle physics, “big data” and such) that have interactive elements or simulations of various types embedded within each story.

The first one that sprung up in our news feed is a piece by [Omar Shehata] on the humble JPEG image format. In it, he explains the how and why of the JPEG encoding process, allowing the reader to play with the various concepts along the way, in real time, within the browser.

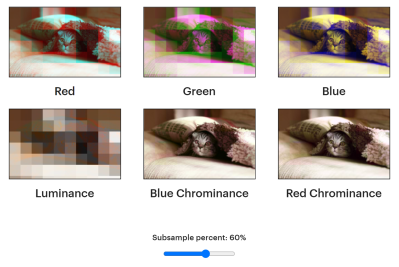

For those not familiar with the format, the first step (which is actually optional) to JPEG encoding is to transform the image from the RGB color space, into a YCbCr (luminance, chrominance) color space. Since the human eye is far more sensitive to luminance (brightness) differences than it is to Cb (chroma relative blueness) and Cr (chroma relative redness) differences, these latter two components can be subsampled by only storing a single value for each, in every 2×2 pixel matrix. JPEG allows other matrix sizes, but 2×2 is the most common.

This sets the scene for the clever bit, that comes next and allows more of that harder-to-perceive chroma information to be discarded. It’s fun to play with the chroma sub-sampling slider and see how the different colours are not equally affected, due to the relative sensitivities of the human eye cone cells.

Next, the three YCbCr components are treated independently to a discrete cosine transform and quantization. This transforms each 8×8 pixel block into 64 discrete spatial frequencies. The JPEG compression level (which you can change) affects how many of the upper-frequency components get discarded, and thus how much of the fine spatial detail gets discarded. This is the main source of JPEG image quality loss. Finally, the compressed blocks are delta encoded, where each subsequent block is coded as the difference from the previous one. Like chroma subsampling, this doesn’t offer any compression on its own but allows the subsequent run-length encoding to be more effective, giving more (lossless) compression. Finally, the whole lot is then Huffman compressed with a unique table stored in the JPEG header. So want to play with JPEGs some more? here’s the GitHub source.

If all of this theoretical stuff is a bit useless to you, perhaps you just want to decode some JPEGs, then here is a speedy library for just that.