For certain high-security devices, such as card readers, ATMs, and hardware security modules, normal physical security isn’t enough – they need to wipe out their sensitive data if someone starts drilling through the case. Such devices, therefore, often integrate circuit meshes into their cases and regularly monitor them for changes that could indicate damage. To improve the sensitivity and accuracy of such countermeasures, [Jan Sebastian Götte] and [Björn Scheuermann] recently designed a time-domain reflectometer to monitor meshes (pre-print paper).

Many meshes are made from flexible circuit boards with winding traces built into the case, so cutting or drilling into the case breaks a trace. The problem is that most common ways to detect broken traces, such as by resistance or capacitance measurements, aren’t easy to implement with both high sensitivity and low error rates. Instead, this system uses time-domain reflectometry: it sends a sharp pulse into the mesh, then times the returning echoes to create a mesh fingerprint. When the circuit is damaged, it creates an additional echo, which is detected by classifier software. If enough subsequent measurements find a significant fingerprint change, it triggers a data wipe.

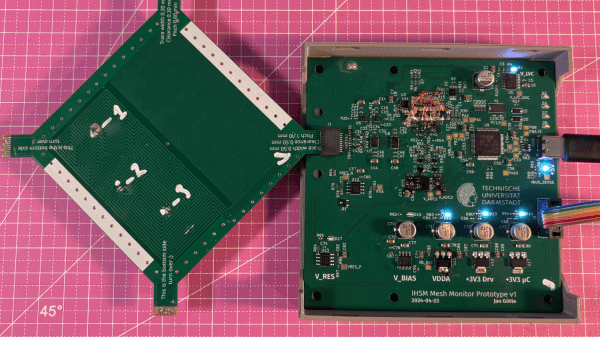

The most novel aspect of this design is its affordability. An STM32G4-series microcontroller manages the timing, pulse generation, and measurement, thanks to its two fast ADCs and a high-resolution timer with sub-200 picosecond resolution. For a pulse-shaping amplifier, [Jan] and [Björn] used the high-speed amplifiers in an HDMI redriver chip, which would normally compensate for cable and connector losses. Despite its inexpensive design, the circuit was sensitive enough to detect when oscilloscope probes contacted the trace, pick up temperature changes, and even discern the tiny variations between different copies of the same mesh.

It’s not absolutely impossible for an attacker to bypass this system, nor was it intended to be, but overcoming it would take a great deal of skill and some custom equipment, such as a non-conductive drill bit. If you’re interested in seeing such a system in the real world, check out this teardown of a payment terminal. One of the same authors also previously wrote a KiCad plugin to generate anti-tamper meshes.

Thanks to [mark999] for the tip!

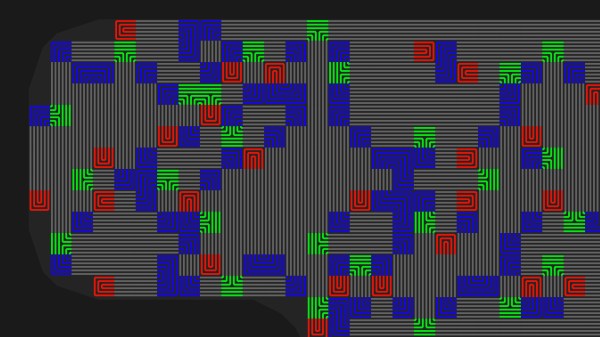

The idea is pretty simple, place traces very close to one another and it makes it impossible to drill into the case of a device without upsetting the apple cart. There are other uses as well, such as embedding them in adhesives that destroy the traces when pried apart. For [Sebastian’s] experiments he’s sticking with PCBs because of the ease of manufacture. His plugin lays down a footprint that has four pads to begin and end two loops in the mesh. The plugin looks for an outline to fence in the area, then uses a space filling curve to generate the path. This proof of concept works, but it sounds like there are some quirks that can crash KiCad. Consider

The idea is pretty simple, place traces very close to one another and it makes it impossible to drill into the case of a device without upsetting the apple cart. There are other uses as well, such as embedding them in adhesives that destroy the traces when pried apart. For [Sebastian’s] experiments he’s sticking with PCBs because of the ease of manufacture. His plugin lays down a footprint that has four pads to begin and end two loops in the mesh. The plugin looks for an outline to fence in the area, then uses a space filling curve to generate the path. This proof of concept works, but it sounds like there are some quirks that can crash KiCad. Consider