PCB design starts off being a relatively easy affair — you create a rectangular outline, assign some component footprints, run some traces, and dump out some Gerber files to send to the fab. Then as you get more experienced and begin trying harder circuits, dipping into switching power supplies, high speed digital and low noise analog, things get progressively more difficult; and we haven’t even talked about RF or microwave design yet, where things can get just plain weird from the uninitiated viewpoint. [Robert Feranec] is no stranger to such matters, and he’s teamed up with one of leading experts (and one of this scribe’s personal electronics heroes) in signal integrity matters, [Prof. Eric Bogatin] for a deep dive into the how and why of controlled impedance design.

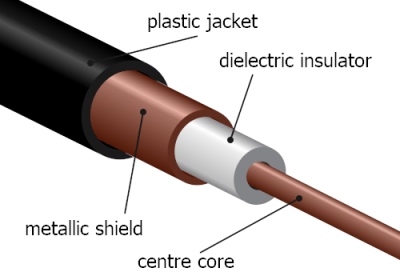

One interesting part of the discussion is why is 50 Ω so prevalent? The answer is firstly historical. Back in the 1930s, coaxial cables needed for radio applications, were designed to minimize transmission loss, using reasonable dimensions and polyethylene insulation, the impedance came out at 50 Ω. Secondarily, when designing PCB traces for a reasonable cost fab, there is a trade-off between power consumption and noise immunity.

As a rule of thumb, lowering the impedance increases noise immunity at the cost of more power consumption, and higher impedance goes the other way. You need to balance this with the resulting trace widths, separation and overall routing density you can tolerate.

Another fun story was when Intel were designing a high speed bus for graphical interfaces, and created a simulation of a typical bus structure and parameterized the physical constants, such as the trace line widths, dielectric thickness, via sizes and so on, that were viable with low-cost PCB fab houses. Then, using a Monte Carlo simulation to run 400,000 simulations, they located the sweet spot. Since the via design compatible with the cheap fab design rules resulted often in a via characteristic impedance that came out quite low, it was recommended to reduce the trace impedance from 100 Ω to 85 Ω differential, rather than try tweak the via geometry to bring it up to match the trace. Fun stuff!

We admit, the video is from the start of the year and very long, but for such important basic concepts in high speed digital design, we think it’s well worth your time. We certainly picked up a couple of useful titbits!

Now we’ve got the PCB construction nailed, why circle back and go check those cables?

Continue reading “What Every PCB Designer Needs To Know About Track Impedance With Eric Bogatin”