A high school friend once related the story about how his father, a chemist for an environmental waste concern, disposed of a problematic quantity of metallic sodium by dumping it into one of the more polluted rivers in southern New England. Despite the fact that the local residents were used to seeing all manner of noxious hijinx in the river, the resulting explosion was supposedly enough to warrant a call to the police and an expeditious retreat back to the labs. It was a good story, but not especially believable back in the day.

After seeing this video of how the War Department dealt with surplus sodium in 1947, I’m not so sure. I had always known how reactive sodium is, ever since demonstrations in chemistry class where a flake of the soft gray metal would dance about in a petri dish full of water and eventually light up for a few exciting seconds. The way the US government decided to dispose of 20 tons of sodium was another thing altogether. The metal was surplus war production, probably used in incendiary bombs and in the production of aluminum for airplanes. No longer willing to stockpile it, the government tried to interest industry in the metal, but to no avail due to the hazard and expense of shipping the stuff. Sadly (and as was often the case in those days), they just decided to dump it.

Environmental Chemistry

The final resting place was to be Lake Lenore, a biologically dead alkali lake near the Grand Coulee in eastern Washington state. The 3,500 pound (1,600 kg) ingots were unceremoniously rolled down into the lake, and the ensuing explosions were pretty spectacular. The video below is newsreel film from the event; it’s pretty low quality, so you might want to check out what just a pound of sodium does when it hits the water.

Watching sodium react so violently with water might just put you in the mood to get in on this action yourself. That’s understandable, but probably not a great idea. Had Lake Lenore not already been devoid of aquatic life in 1947, it might well have been after the government got done with it. Sodium combines with water to produce an aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide and copious amounts of hydrogen gas, in a violently exothermic fashion. None of this is good for critters and it’s likely to be received poorly by law enforcement and wildlife protection agencies alike.

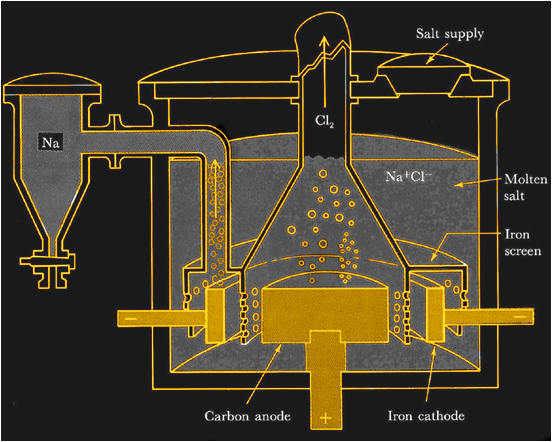

How Metallic Sodium is Made

If you insist on trying your hand at making your own sodium metal you’ll face some challenges. On a commercial scale, metallic sodium is made by electrolysis of molten sodium chloride. With temperatures pushing 800°C and currents in the kiloamp range, it’s not exactly DIY-friendly.

There are non-electrolytic methods, though, and NurdRage has a helpful guide to a solvent extraction of sodium that is much easier and yields a fair amount of the pure metal. It’s not without its drawbacks, though; the best solvent is dioxane, a carcinogenic and noxious substance in its own right.

If you do choose to make sodium, or just order some online, please have a plan for disposing of it. We know that times were different back in the 40s, and that Lake Lenore was already dead, but it’s hard to watch that video and not cringe.

[via r/whoadude]

An ex-colleague once “needed” to get rid of a lump the size of your fist – he threw it over the side of the Isle of Wight ferry.

is he now an inmate ?

Had a chemistry teacher that got rid of some potassium down the sink in the prep room. Both labs got evacuated as the resulting smoke was initially thought to be the school boiler (below the labs). What the hell they were thinking is anyone’s guess.

Kind of like when we see doctors smoking. “What were they thinking…” is a common refrain.

My girlfriend is a doctor and at least two third of her colleagues smoke.

The culture in medicine doesn’t exactly support wanting a long life.

It was a while ago and I don’t remember all the details. We produced some hydrogen sulphide under a fume hood. The reaction vessel was venting gas, which we would bubble though water to use in the next stage of what we were doing. Without thinking, I started walking away from the fume hood with my beaker of infused water. I got about 5 feet away and had to run back.

The “fun” part, is someone spilled the whole vessel that was creating the H2S down the drain under the fume hood (made 200mL of liquid). They ended up evacuating fair sized area of the city because they thought there was a massive natural gas leak.

Years ago I worked at a cancer research institute, in a lab that had been added on to the main building. Once my boss started working with some selenium compounds; I forget what it was precisely, but I remember the little vial from the supplier noted “WARNING: STENCH, characteristic odor of rotting radishes”. Well he starts working with it, gloved up, working in the hood, all well and fine. WE can’t smell anything…

About fifteen minutes later people come pounding down to our lab to complain; apparently when the hood was put in, they didn’t make the exhaust stack high enough, and that day the wind was just right to send the exhaust right into the main building’s air intake…. people were fleeing the building, and more than one puked.

We know that times were different back in the 40s, and that Lake Lenore was already dead, but it’s hard to watch that video and not

cringesmile.FTFY

Hehehehehe…. :D

A friend of mine flushed a cm^3 of Na down a toilet in his college dorm. He had it wrapped in a bit of plastic with holes to delay the onset of the reaction.

It blew a toilet off the wall in the floor below!

He was caught…

something about a college kid running down the hallway laughing tipped them off.

Oh, that’s outrageous, why did you rat out him?

:o)

We put it in a sock, then flushed it.

Speaking of which, that reminded me the video by Cody’s Lab and The King of Random “Don’t Flush Sodium Down The Toilet”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CEC64Bqeajs

And for anyone who really wants to try molten NaOH electrolysis to get some sodium, I don’t remember where, but I’ve read that wearing eye protection is essential because tiny particles of molten NaOH are sprayed which could seriously damage the eyes.

It’s rather easy to make sodium. All that is needed is a rough DC supply, a tubular-shaped incandescent bulb, some sodium salt with a low melting point (or what I used, some NaOH) and a tin can. I melted the NaOH in the tin on the stove, put the light bulb, illuminated, into the molten NaOH, and put the DC between the tin and the bulb. No need to reveal the polarity I used, right?

The sodium ions went right through the glass to receive their missing electrons, and collected inside the bulb. Eventually the bulb’s glass had endured enough of the NaOH torture and punctured, but I had collected maybe half a gram of pure, metallic sodium.

Every young lad, regardless of age or gender, who has the slightest enjoyment of experimental chemistry or pyrotechnics should try it. “Don’t try this at home, folks!” (Addito salis grano.)

So… this made me curious. Why was lake Lenore dead? Is it still dead today?

I can’t find anything on the internet about this, all I can find is that there are problems with fish poachers on the lake today. Well.. I guess that means it isn’t dead anymore!

I’m surprised at your lack of web searching skill, 10s on Wikipedia says “The Columbia Basin Project changed this in 1952, using the ancient river bed as an irrigation distribution network. The Upper Grand Coulee was dammed and turned into Banks Lake. The lake is filled by pumps from the Grand Coulee Dam and forms the first leg of a one-hundred-mile (160 km) irrigation system. Canals, siphons, and more dams are used throughout the Columbia Basin, supplying over 600,000 acres (240,000 ha) of farm land. ”

So clearly the lakes were dead and alkaline with almost no rain water pre 1952 and are now fresh water from irrigation water supplied via grand coulee.

What, this Wikipedia? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lake_Lenore_(Washington)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Coulee#Modern_uses

A lot of references to Lake Lenore say it’s between Alkali Lake and Soap Lake, and that these lakes were created when a glacier melted after the Ice Age. Looks like the toxicity is an area-wide phenomenon. May have been that the lakes could neither drain water out nor had significant water coming in, and some sort of minerals got concentrated by the lake slowly evaporating over thousands of years.

Same goes with high sulfur and arsenic areas out west due to the geology… not necessarily the issues from mine operations that is another detail.

A friend tells of many years ago working on aircraft piston engines, where the valves had a sodium core for cooling. When a valve was replaced, they would grind off the end, and place it under a dripping faucet…Interesting fireworks.

In german engines sodium filled exhaust valves are super common. Nearly all turbo diesels from the eighties onwards have them. No need to search for aircraft engines; take an old mercedes lump and you have your sodium filles valves.

Some VWs too

And Saab 900 from the 80´s

IIRC, the B-17 used sodium filled valves in its engines.

Wonder if that made them hard to recycle?

When I was in high school, my science teacher told us about many years before when a kid decided to steal a chunk of sodium (I think, it might have been potassium – it was stored in a jar of kerosene) from the science lab. He put it in his backpack in one of the outer pockets, later in the day it started smoking and they evacuated part of the building. I don’t remember if it caught fire or exploded though.

Ah, sodium metal :D

I did the same. I cut about 1/4 cubic cm of it during the pause in physics class, it was stored in mineral oil, and wrapped it in a … paper tissue.

It held until the next class, the math class, where, sitting with my accomplice at the back of the classroom, we attempted immediately to share the awesome corpus delicti in two parts with a knife, on the table itself.

The moist of my fingers reacted and the metal started melting and boiling. I quickly wrapped it back in the paper tissue and threw it two meters behind my back near the wall of the classroom. We then stupidly looked at the teacher gesticulating as the smoke and flames were rising behind us.

When we turned the head to check what the teacher was alarmed of, we took the appropriate terrified look while watching the courageous math teacher stamping with her high heels on the pink flaming substance.

As she was wondering what happened, we tipped her the previous class must have put a pyrotechnic engine in the class to surprise her. And spend the rest of the math teaching sweating in fear, the second half of the sodium metal being trapped on the table, melted and solidified flat between a classbook and the table.

When the class finished we waited everybody to go then dumped it on the terrasse where it burned with a nice glow. We weren´t caught fortunately, and no damage had been done. This hour of terror during the whole math class, afraid the second half would catch fire, was unforgettable, but today I laugh when I think about it.

Our high school chemistry teacher, whom we regarded as outdated and hopeless, was actually a nerd when she was in school herself. We joked that the last thing she had learned was Chadwick’s discovery of the neutron in 1932, but it was >>she<< who suggested to us that sodium wasn't good enough, and that potassium in water was much more incendiary. We spent altogether too much time considering how we might get a bit of potassium to place in the drinking fountain that lurked outside her classroom door. It's only now, decades later, that we wonder if she might have made that suggestion deliberately, hoping to see the pyrotechnics.

Man, that would make a lot of batteries. I think at the time President Truman was wanting investment in solar technologies and I’m guessing not using sodium ion batteries or molten Na systems. I’m thinking he wasn’t the most nuclear friendly for power utilities either and more for bombs.

https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2017-04-08/nuclear-power-s-original-mistake-trying-to-domesticate-the-bomb

In regards to sodium ion batteries, I was reading there are projections for sodium batteries in the next ten to twenty years since the standard reduction potential isn’t bad and sodium is an abundant element.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sodium-ion_battery

https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/the-global-market-for-sodium-ion-batteries-will-grow-from-420-million-in-2017-to-12-billion-by-2022-with-a-compound-annual-growth-rate-cagr-of-239-for-the-period-of-2017-2022-300578179.html

More bad science outrage? Lenore is between Alkali Lake to the north and Soap Lake to the south. You think an extra 20,000 pounds of sodium did what?

I can’t tell you what it did but it sure as hell was wildly irresponsible

What >>would<< have been the "responsible" way to get rid of it?

I don’t know, I’m not an expert on disposal of industrial materials. Today this likely would have been preceded with at least some halfassed research on possible environmental or other impacts, rather than yesteryear’s reckless attitude toward the environment.

Lets do some halfassed research…

20 tons of sodium

+ 24,100,000 m^3 of water.

https://sciencing.com/calculate-ph-naoh-7837774.html

Which gives us a ph of 9.3 if the water started at 7. Which is about as strong as baking soda.

Why don’t you try raising the pH of your fishtank to 9.3 from 7 and tell me how that goes?

Should have used it as a CO2 scrubber then sold the washing soda.

Given

~120million tons of NaCl per cubic mile of seawater

This equates to

~40 million tons of sodium per cubic mile of seawater

So, 20 tons of sodium in a cubic mile of sea water would equate to an additional 0.5ppm or so of sodium ions.

So, the ocean would also be a good disposal site.

As they say, “Dilution is the solution”.

Put the sodium in oil-filled glass jars. Put the jars in excelsior-filled wooden crates. Put the crates in that warehouse in between the Ark of the Covenant and the Roswell alien.

Irresponsible to add a tiny fraction of NaOH to an alkali lake? That is Drano – as used to clear drains. You have been hyper-sensitized to potential environmental hazards. I suggest doing some order of magnitude estimates before making decisions. (You could collect the NaOH solution afterwards and add HCL to get table salt I suppose.)

Salted drains? Yum.

So dumping waste is irresponsible. CO2 is usually considered waste. We also know it harms our environment. We should stop dumping it in the atmosphere. YOU are dumping it into the atmosphere. About 1.5kg per day! Stop breathing goddammit!

There is about 45*10^18 kg of salt in the oceans. What happens if you dump 10 tons of sodium into that? Very close to nothing….. How this scales to the lake… I don’t know. Without knowing more, it is quite possible that the effects are negligible. Maybe back then they thought it through. Maybe they didn’t. I don’t know.

Plant a tree or some produce everyday now… especially in desertified areas (maybe extra there for the work to make the clay lining bed to hold more water).

Gotta love those dubbed sound effects.

That frog… https://www.space.com/22772-frog-photobombs-nasa-moon-launch.html

Thaks for that link .. the picture, and the accompanying explanation, were ribbiting.

” NASA officials wrote in an image description. “The condition of the frog, however, is uncertain.” “

We had an exciting science teacher at school. I remember one sodium or potassium demonstration that started with a small slither into a basin. Pleased with the result, and perhaps dreading the though of all the effort of putting the lid back on the jar, she lead the entire class to the river. One of the students got the honour of tossing the entire remaining content into the river. She always enjoyed a bit of molecular drama in her science class.

I’ve seen baby snakes start with a small slither.

For the curious – the explosive nature of sodium metal in water seems to be that as the sodium initially reacts with water it develops an electrical charge. As the charge grows it forces filaments of sodium metal away from each other increasing the surface area/volume ratio. This transition happens very rapidly once it starts, pushing the reaction rate enormously, which, of course increases the charge, further accelerating the process. Then – boom. This fits with many descriptions where the lump gradually softens, becomes semi-fluid and then – explodes.

The sodium reacts with the water. It gets hot and releases hydrogen. What happens next is obvious.

At Tommy’s Physics Picnic (2010?), we played around with sodium metal and water buckets. _Highly_ variable, which makes it a bit scary.

The reaction speed depends on the surface area contacting water. You store it in oil, and then cut a slice off. When you cut, the knife drags some oil along with it. You can try to wipe off the oil, but still it’s not like you’re going to give it a good scrub with soap and water…

Sometimes it fizzles, sometimes it burns, sometimes it explodes. Give me good old predictable gunpowder anyday. Or hydrogen-filled baloons. Heck, even high-voltage shenanigans are more consistent.

Quite partial to 2ltr pop bottles and a small amount of dry ice. A teaspoon of water in the bottom. Drop in a few bits of dry ice, tighten cap very well and then place somewhere hidden, usually inside of large amplifying containers like rubbish bins.

Then just wait for the boom.

Best done at night on campsites after the noise curfew.

So I would guess adding soap or some other surfactant to the water would accelerate the reaction?