Somewhere between the early tires forged by wheelwrights and the modern steel-belted radial, everyone’s horseless carriage rode atop bias-ply tires. This week’s film is a dizzying tour of the Brunswick Tire Company’s factory circa 1934, where tires were built and tested by hand under what appear to be fairly dangerous conditions.

It opens on a scene that looks like something out of Brazil: the cords that form the ply stock are drawn from thousands of individual spools poking out from poles at jaunty angles. Some 1800 of these cords will converge and be coated with a rubber compound with high anti-friction properties. The resulting sheet is bias-cut into plies, each of which is placed on a drum to be whisked away to the tire room.

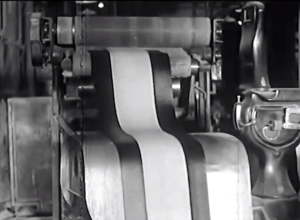

The tread stock is made from raw rubber and seven secret ingredients, then beaten in Banbury mixers. Once each 800lb batch is made, it’s off to the mills for more additives and heavy-duty kneading. The stock is pressed out into a flat, wide band and cooled over 300 feet of rolling conveyor. At this point, an adhesive strip is applied to the underside that will help keep the tread attached to the carcass for the life of the tire.

The tread stock is made from raw rubber and seven secret ingredients, then beaten in Banbury mixers. Once each 800lb batch is made, it’s off to the mills for more additives and heavy-duty kneading. The stock is pressed out into a flat, wide band and cooled over 300 feet of rolling conveyor. At this point, an adhesive strip is applied to the underside that will help keep the tread attached to the carcass for the life of the tire.

Each tire is built up by hand around a wide drum. A couple of plies are applied and smoothed, and rollers pinch the edges down while squishing out any trapped air. The beads are added next, followed by flipper strips that keep the sidewalls attached. These strips are punched down over the bead, and then the rest of the plies are smoothed on.

Before adding the tread, the Brunswick Tire Corporation wishes to briefly interrupt this tire assembly for an educational message about their patented double shock-absorbing technology. Underneath the tread of these fine tires, you’ll find two extra layers of cording that’s been treated with special cushioning. This cording and the adhesive layer applied to the underside of the tread stock work together to protect the tire body from high-speed road shock. Any jalopy equipped with Brunswick Super Service Tires is sure to master boardwalk and quagmire with aplomb.

You may notice that what’s coming off the line barely resembles a tire. That’s because it must be formed in two stages. First, the tire is prepared for the curing mold inside a forming box. An empty water bag is installed and the tire is sort of vaguely formed around it. Now it’s ready for the vulcanizer, where heat and pressure are applied to the inside and outside of the tire in equal amounts. Inside the vulcanizer, 300°F water is blasted into the water bag at 240psi while the outside is bathed in steam. No wonder that guy is shirtless.

You may notice that what’s coming off the line barely resembles a tire. That’s because it must be formed in two stages. First, the tire is prepared for the curing mold inside a forming box. An empty water bag is installed and the tire is sort of vaguely formed around it. Now it’s ready for the vulcanizer, where heat and pressure are applied to the inside and outside of the tire in equal amounts. Inside the vulcanizer, 300°F water is blasted into the water bag at 240psi while the outside is bathed in steam. No wonder that guy is shirtless.

No promotional look-at-our-factory film would be complete without some boasting about inspection standards and rigorous testing procedures, but Brunswick did some interesting things in both departments. To wit, the research lab: regular and experimental tire recipes were created and tested in a scaled-down version of the plant. Tiny batches of rubber were blended in tiny Banbury mixers and baked in tiny ovens. Unfortunately, they weren’t then made into tiny tires, but the materials underwent exhaustive testing for tensile strength and heat resistance.

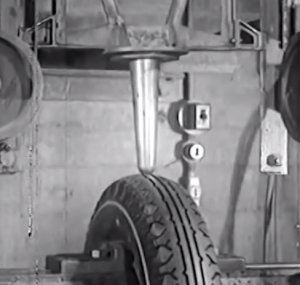

Full-size tires were subjected to all kinds of tests in the torture chamber. For instance, some were way over-inflated to the point of bursting and others were dropped repeatedly on a cleat to simulate curb checking. Tires were runtime-tested for thousands of miles against a dynamometer and then compared to competing tires. But the best possible use of space and time has to be the pile driver test. Here, a steel wedge is raised seven stories along a track and dropped on the unsuspecting tire. After testing, tires were cut down in stages for ply-by-ply analysis.

Full-size tires were subjected to all kinds of tests in the torture chamber. For instance, some were way over-inflated to the point of bursting and others were dropped repeatedly on a cleat to simulate curb checking. Tires were runtime-tested for thousands of miles against a dynamometer and then compared to competing tires. But the best possible use of space and time has to be the pile driver test. Here, a steel wedge is raised seven stories along a track and dropped on the unsuspecting tire. After testing, tires were cut down in stages for ply-by-ply analysis.

By the way, this is the same Brunswick that’s been cranking out pool and billiards tables since 1845. Prior to Prohibition, they had also manufactured ornate bar fixtures but were forced to diversify, so they branched out into automobile tire and rubber toilet seat concerns. By the time of this film, he had sold the tire division to B.F. Goodrich, retaining the Brunswick name.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YZISUfi-6Ik

Retrotechtacular is a weekly column featuring hacks, technology, and kitsch from ages of yore. Help keep it fresh by sending in your ideas for future installments.

Speaking of Brunswick, you should dig up some video of early automatic bowling systems for the next retro. Mechanical works of art.

This is happening.

Those machines have always fascinated me… they are bathed in the mysteries of bright lights on facade boards and oiled wood…

I saw this one, http://youtu.be/1MOLAaYZNnA a Brunswick ad from the 60’s. Jump to 9:00 for the mechanical pinsetter.

The commentator has an interesting accent. New England trying to sound British?

Early variant of the “Mid-Atlantic dialect” (so named as it’s a compromise between American and British accents) popular among actors and upper-class people from the 30s to the 60s. This was not an natural dialect, but rather an affection one would learn in an effort to sound “proper”

Yup. It was supposedly ‘clearer’ for broadcasts and recordings of the time.

Now broadcasters go for an accent that sounds like the Iowa/Illinois/Wisconsin area; i.e. no accent at all.

As an Illinois native, everyone outside of the areas you mentioned think I have an accent.

lol, that’s funny… IA, IL, and WI most certainly have accents, and they’re each slightly different from each other. Amazing how many people think their particular region is accent free.

Think Gilligan’s Thurston Howell…

An Ivy League affectation that spread into early/mid broadcasting as the “upper class” tried to redeem broadcasting and the theatre arts from being just lowbrow entertainment for the “lower class” (or so they claimed).

Leslie Nielsen’s father.

I gotta get me some Brunswick SuperService tires!

I’d like to see how today’s tires stand up to the Sprague machine and pile driver.

“high anti-friction properties” – also known as a lubricant ;-)