It seems [Pete Prodoehl] was working on a project that involved counting baseballs as they fell out of a chute, with the counting part being sensed by a long lever microswitch. Now we all know there are a number of different ways in which one can do this using all kinds of fancy sensors. But for [Pete], we guess the microswitch was what floated his boat — likely because it was cheap, easily available and replaceable, and reliable. Well, the reliable part he wasn’t very sure about, so he built a (not quite) Useless Machine that would conduct an endurance test on the specific switch brand and type he was using. But mostly, it seemed like an excuse to do some CAD design, 3D printing, wood work and other hacker stuff.

The switches he’s testing appear to be cheap knock-off’s of a well known brand. Running them through the torture test on his Useless Machine, he found that the lever got deformed after a while, and would stop missing the actuator arms of his endurance tester completely. In some other samples, he found that the switches would die, electrically, after just a few thousand operations. The test results appear to have justified building the Useless Machine. In any case, even when using original switches, quite often it does help to perform tests to verify their suitability to your specific application.

Ideally, these microswitches ought to have been compliant to the IEC 61058 series of standards. When switches encounter real world loads running off utility supply, their electrical endurance is de-rated depending on many factors. The standard defines many different kinds electro-mechanical test parameters such as the speed of actuation, the number of operations per minute and on-off timing. Actual operating conditions are simulated using various types of electrical loads such as purely resistive, filament lamp loads (non-linear resistance), capacitive loads or inductive loads. There’s also a test involving a locked rotor condition. Under some of the most severe kinds of electrical loads, a switch may be expected to last just a few hundred operations. But if the switch is used for low power applications (contact current below 20 mA), then it is expected to last up to its mechanical endurance limit. For most microswitches, this is usually in the range to 100,000 to 300,000 operations.

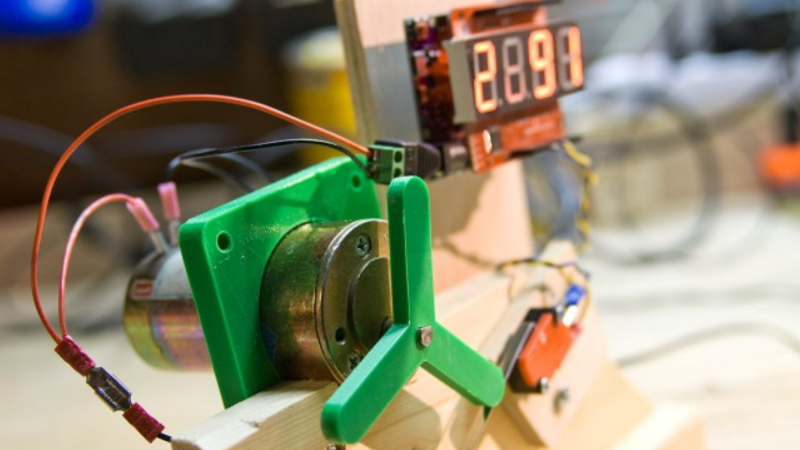

Coming back to his project, his first version was cobbled together as a quick hack. A 3D-printed lever was attached to a motor fixed on a 3D-printed mount. The switch was wired to an Arduino input, and a four-digit display showed the number of counts. On his next attempt, he replaced the single lever with a set of three, and in yet another version, he changed the lever design by adding small ball bearings at the end of the actuator arms so they rolled smoothly over the microswitch lever. The final version isn’t anywhere close to a machine that would be used to test these kind of switches in a Compliance Test Laboratory, but for his purpose, we guess it meets the bar.

For those interested, here is a great resource on everything you need to know about Switch Basics. And check out the Useless Machine in action in the video below.

At the very least it makes a compelling case to bring to the higher ups that you need to spring for the optical sensors in this project…

It depends on the rate of actuation. Opto-interruptors have issues to. The Hfe of the light recieving transistor changes with age. At low actuation rates switches are more predictable.

If you buy cheap Chinese switches, don’t be surprised when they don’t perform as well as well built switches?

Good switches are Chinese as well, so why bring up “Chinese” at first ? MAGA illusion ?

There are good Chinese switches too of course but there tends to be a correlation between knocking off an existing brand and cutting corners elsewhere too (like in this example) and typically you see that more often in countries that make a lot of electronics and don’t care as much about US IP laws. Cheap knockoffs of a well known brand are more likely to be made in China than, say, South Africa, but that certainly isn’t always the case of course or a vilification of China either.

Hmm. Mine are *probably* the brand time type. Maybe. I’ve got a box of switches that look identical, sourced from IBM in the 80’s. They had bought too many or something, my dad worked at the local plant, I ended up with boxes of them. The switch that actuated the brake lights on my car wore out, and I cobbled one of those onto the petal to operate the lights. It’d wear out, (the lever) because it wasn’t really meant for what I was doing of course. But I had cases of them. I’d just replace it every couple of months. Eventually, I’m going to run out of those things I guess… I’m kind of planning to keep that car for the next 30 years or so. Maybe I should get around to something a little more durable….

I would add an infrared sensor to the rotational part and then compare the real number of presses with those counted by switch itself.

That’s one of the things Endurance Testers used in Test Laboratories have. Besides adjustable On and Off timings. Adjustable actuator pressure/force settings. Travel adjustment. Among other things.

I don’t see any pull-up resistor, using the build-n +20K pull-up is probably well below the spec’ed wetting current for those kind of switches

YMMV, but in my experience I try very hard to _not_ use micro-switches. I just have never had great experience with them, worst case was a garage door controller that kept failing because of the micro-switches. Considering they are used everywhere, the problem must have been with the design engineer (i.e. me) but I really try to avoid them these days.

No, it’s not just you. Even the finest kind die unpredictably in the real world.

I was going to say “Why not buy a good switch directly from trusted source like digikey, mouser, etc in the first place?”

BUT this article is not the same has what Pete is saying on his website. Pete wanted to test microswitches. So have fun buying cheap switch for your test!