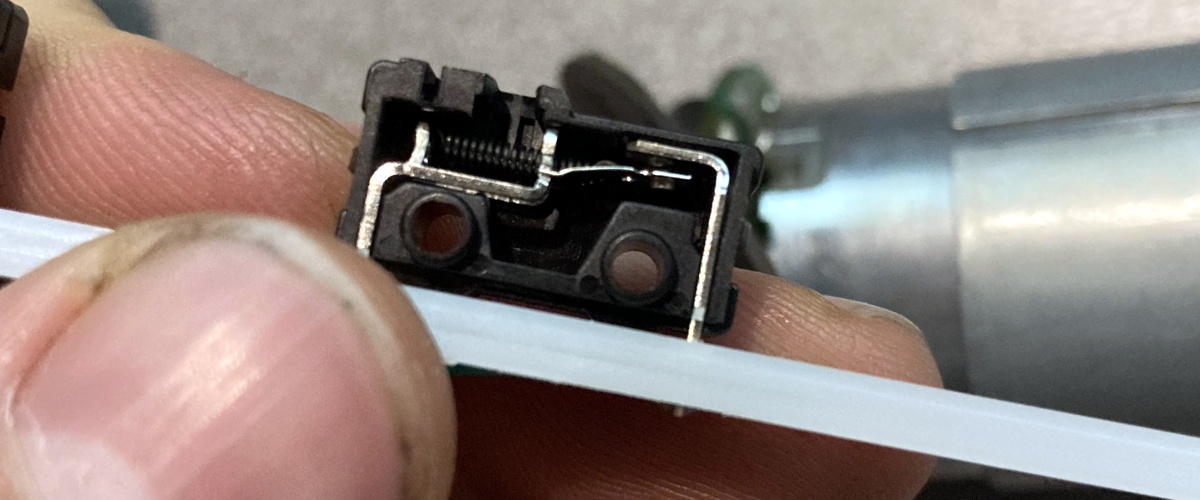

Our homes are full of technological marvels, and, as a Hackaday reader, we are betting you know the basic ideas behind a microwave oven even if you haven’t torn one apart for transformers and magnetrons. So we aren’t going to explain how the magnetron rotates water molecules to produce uniform dielectric heating. However, when we see our microwave, we think about two things: 1) this thing is one of the most dangerous things in our house and 2) what makes that little turntable flip a different direction every time you run the thing?

First, a Little History

People think that Raytheon engineer Percy Spenser, the chief of their power tube division, noticed that while working with a magnetron he found his candy bar had melted. This is, apparently, true, but Spenser wasn’t the first to notice. He was, however, the first to investigate it and legend holds that he popped popcorn and blew up an egg on a colleague’s face (this sounds like an urban legend about “egg on your face” to us). The Raytheon patent goes back to 1945.

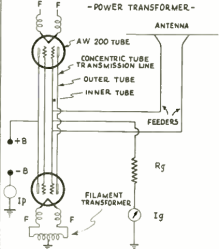

However, cooking with radio energy was not a new idea. In 1933, Westinghouse demonstrated cooking foods with a 10 kW 60 MHz transmitter (jump to page 394). According to reports, the device could toast bread in six seconds. The same equipment could beam power and — reportedly — exposing yourself to the field caused “artificial fever” and an experience like having a cocktail, including a hangover on overindulgence. In fact, doctors would develop radiothermy to heat parts of the body locally, but we don’t suggest spending an hour in the device.