By the early 20th century, naval warfare was undergoing drastic technological changes. Ships were getting better and faster engines and were being outfitted with wireless communications, while naval aviation was coming into its own. The most dramatic changes were taking place below the surface of the ocean, though, as brave men stuffed themselves into steel tubes designed to sink and, usually, surface, and to attack by stealth and cunning rather than brute force. The submarine was becoming a major part of the world’s navies, albeit a feared and hated one.

For as much animosity as there was between sailors of surface vessels and those that chose the life of a submariner, and for as vastly different as a battleship or cruiser seems from a submarine, they all had one thing in common: the battle against the sea. Sailors and their ships are always on their own dealing with forces that can swat them out of existence in an instant. As a result, mariners have a long history of doing whatever it takes to get back to shore safely — even if that means turning a submarine into a sailboat.

Pigs of the Sea

The first generation of militarily important submarines were, to modern eyes, terribly primitive affairs. Compared to surface vessels of the day, they were tiny, had little in the way of armor, had a limited range, and were not particularly fast. They also spent comparatively little of their time submerged, mostly operating on the surface until it was time to attack. Before periscopes were introduced, this meant a commander would need to surface his sub enough to pop the conning tower above the water to get a bearing before submerging again. To surface mariners, this looked like the swimming of porpoises, which they called “sea pigs”, so they dubbed submarines “pigboats.”

Despite their image, the submarines of the US Navy were quite sophisticated by the time World War I came around. This was the era of the R-class boats, built for coastal defense and harbor patrol. These boats, like most submarines at the time, had hybrid propulsion: diesel engines turned generators to charge massive battery banks for submerged operation, with electric motors turning the screws. They carried four torpedo tubes and had a deck-mounted 3″ gun for surface attacks, could make 13 knots (25 km/h) on the surface, and carried enough fuel to cover 3,700 nautical miles (6,900 km).

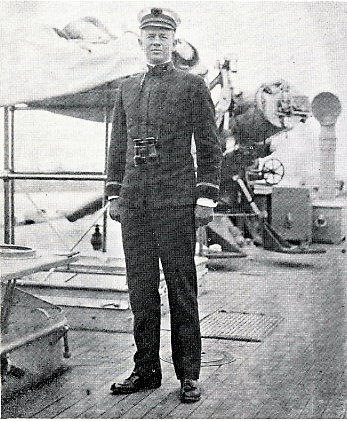

The R-14 (submarines were not given proper names at the time) was one of the 27 boats of the class. Built in 1918 and based out of Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, the boat was used to train crews in submarine warfare and to conduct search and rescue missions. It was on one such search mission that the R-14 would test the limits of the boat’s theoretical range as well as the seamanship of her crew.

On May 2, 1921, R-14 was dispatched to search for a missing vessel, the USS Conestoga. The ocean-going tug had set sail in late March from Mare Island off the coast of California, destined for American Samoa with a barge full of coal. She was supposed to make a port of call at Pearl Harbor but had never been heard from, so R-14 and a flotilla of other subs were sent to look for her.

After days of fruitless searching, R-14 turned back to Pearl. By May 10 she was 100 nm (190 km) southeast of the big island of Hawaii when things started to go sour. The executive officer and acting commander of the boat, Lt. Alexander Douglas, was informed by his engineering staff that the boat was inexplicably out of fuel. By all accounts, she had 10,000 gallons of diesel in her bunkers when she left Pearl eight days before, and should have had plenty left. But she was now suddenly adrift.

Make It So

The skipper ordered a distress call sent. The call was received by sister boat R-12, also on the search and rescue mission, and relayed to Pearl Harbor. The distress message was received, but R-14 never received the acknowledgment. As far as they knew, they were alone and adrift.

Lt. Douglas took stock of the situation. The batteries were partially charged, but even fully charged they’d never get the boat back to Pearl. They had provisions for only five days, and they appeared to have a dead radio and could expect no help. Things looked dire, and like sea captains before and since, Lt. Douglas turned to his chief engineer for solutions.

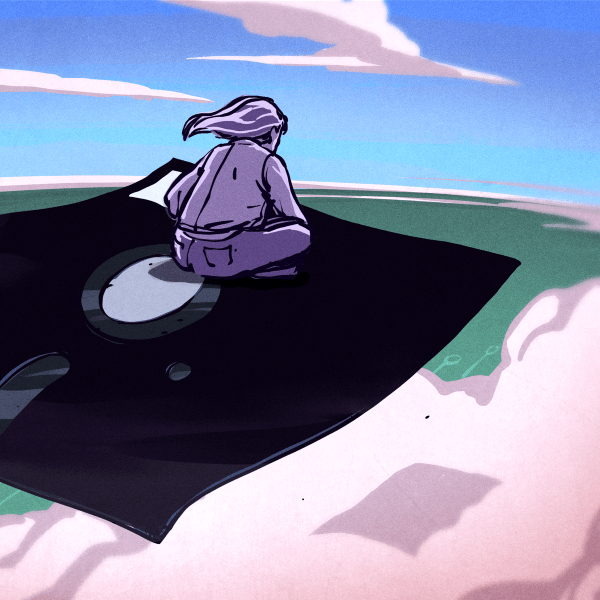

Lt. Roy Trent Gallemore was a US Naval Academy graduate at the start of his career. Perhaps because of his youth, and perhaps because of his relatively recent experiences at the Academy, Gallemore came up with an unusual idea: turn the submarine into a sailboat. They could rig masts and arms to the superstructure of the boat, and make sails out of the crews’ hammocks. It wouldn’t be pretty, and it wouldn’t be fast, but it would get them going again.

Lt. Douglas gave the go-ahead to the unconventional idea, and all hands got to work. Some sewed hammocks together to make sails, other found whatever they could to rig them. The torpedo loading crane was brought on deck and assembled; it would serve as a mast for a foresail made of twelve hammocks. Bunk frames were disassembled to make the yards, and the motley assembly was unfurled. The sail caught the wind, and they started slowing making way. It was only 1 knot (1.8 km/h), but it was enough for steerage, and a lot better than being becalmed.

The crew continued putting on sail. Six blankets were stitched together to make a mainsail that was rigged to the apparently useless radio antenna mast on the conning tower. That added another 0.5 knot (0.9 km/h) to their speed, but Lt. Gallemore wasn’t finished yet. He ordered a third sail rigged, this time of eight blankets and rigged to a third mast by the stern. With a foresail, a mainsail, and now a mizzen, the R-14 was a three-masted square-rigged sailing vessel, the first and only submarine to be so rigged.

All for Naught

The R-14 continued under sail for four days, making 2 knots (3.7 km/h) at best. It was enough, though — they sighted Cape Kumukahi on Hawaii on May 13, and two days later they made it into Hilo Harbor using battery power. They topped off their fuel and fresh water tanks, serviced the batteries, and set sail to their home port of Pearl Harbor, arriving safely on May 17.

Thanks to Lt. Gallemore’s ingenuity and the seamanship of her crew, the R-14 survived the ordeal. That’s more than can be said for the Conestoga; the tug they were looking for was found in 2009 off the Farallon Islands, not far from San Francisco and thousands of miles from where the subs were searching. They had been on a fruitless mission to rescue fellow mariners long since claimed by the sea, but their seamanship and willingness to do whatever it took got the R-14 and her crew safely home.

Submarines never had and still don’t have armor…the thick metal you might see in accurate cutaways is just structural.

That’s true, but I was comparing subs to armored surface ships.

In fact, the superstructure of WW2 U-boats (on top of the conning tower) was made of light armour plate, to protect watch crews and the commanding officer from light weapons fire.

Granted, there was no attempt at armouring against heavy shells. A few aircraft (The “Tsetse” variant of the Mosquito) were fitted with 45mm solid-shot cannon, which would have made a pretty poor anti-tank gun at the time, but was reportedly quite effective against submarines.

British submarines of the day make an interesting study in bad engineering driven by poor requirements analysis. Check out the K-class; steam powered behemoths capable of 24 knots, but you can imagine what a crash submerge looks like when you’ve got a steam boiler running. Of 18 made, only one took part in combat, launching a torpedo which hit a U-boat amidships but failed to detonate. Six sank, all in accidents.

I’d have said heroic engineering driven by appalling requirements analysis. Nobody said “submarine that paces battlecruisers is not possible”, they said “given these constraints this is our engineering solution”. Sometimes that engineer urge of “don’t tell me it can’t be done!” isn’t the right answer.

Meanwhile many, many more boats of humbler ambition gave excellent service and eventually demonstrated what good requirements looked like. And still had a horrifying accident rate by our standards. Risk was regarded differently then.

If you want really scary, the submarine museum in Gosport has one from the 1890s you can go inside…

Methinks it was also a poor understanding of what exactly they had constructed.

A sawed-off double barreled shotgun isn’t a sniper rifle. If you’ve got a submarine that can’t dive in a hurry, but can remain submerged and can move around fast, you use it as such.

Shout out to the submarine museum, well worth a visit – and nip up the road to the only hovercraft museum in the world!

The mini-subs get me, I watched the film “above us, the waves”, you just can’t imagine how they even got the guys into those mini-subs with their GINORMOUS BALLS OF STEEL.

How about 1863? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H._L._Hunley_(submarine)

But … modern nuclear submarines are all steam powered, AFAIK. And it is not like you could safely shutdown a nuclear fission steam boiler on a short notice.

Actually, you *can* shut down a nuclear reactor quickly – that’s precisely what the SCRAM switch is for. You tend to use it when the cooling system or the containment fails, or is in imminent danger of failure.

The problem was that a coal or oil fired boiler needs a hefty air supply and exhaust pipe in order to function, and carries an awful lot of residual heat after you yank those huge hull penetrations closed, making conditions inside the sub rapidly intolerable. A diesel engine needs much less of that, but the induction and exhaust valves were still often problematic anyway.

Well it seems as a similar or same problem, (residual heat) but modern engineers solved it, while the WWI era engineers didn’t, or probably didn’t have a clue it would be a problem. If you look at the general plan of an thermodynamic machine, there is a heat source, the machine and a heat sink. Now, you generally rarely can turn off any significantly large heat source fast.

Nuclear engineers are aware of the risks of reactors left without cooling – in their case, there is a bypass (reactor cooling) around the thermodynamic machine to prevent destructive build-up of heat at the heat source when machine is not conductive for the thermal energy.

Steamboat design engineers probably didn’t consider residual heat a problem so they didn’t design boilers with bypass cooling, and steam boilers require water boiling temperature and elevated steam pressure to start circulating the power. All they needed to do was to add additional valve and piping, bypassing steam engine (or turbine) and carrying bellow-boiling-point hot water from boiler directly to condenser unit after the fire is put down.

The choice of a square rig is somewhat curious. I guess if the wind was directly behind their desired course then it kind of makes sense; otherwise, a junk rig would have been a better choice in just about every way, in particular because it gives better performance in anything except direct downwind sailing while greatly reducing the loads on the sailcloth (read: hammocks and blankets) and reducing the risk of tearing.

Wonder if the Naval Academy would have covered that detail, in that time period?

I’m guessing it was taught, the military can be slow to adapt at times…

B^)

A friend attended the Merchant Marine academy in the ’90s, they still taught sailing.

It depends on what the boat has in stores. Junk rig takes a lot more line than a square rigger and battens. Also, it may not have been in the minds of the engineers/officers on board. Seeing a junk rigged sailboat is pretty rare in the US today, let alone back in the early 1900s.

A square sail would be easier to make from blankets and sheets which happen to be square.

Did they ever found out why they ran out of fuel. Did they had a leak, did they all use it, was their a problem with the bookkeeping? It’s very interesting that they turned it into a sailboat… but the end of the story

“They topped off their fuel and fresh water tanks, serviced the batteries, and set sail”

leaves us (technically interested) readers with an unsatisfied feeling to this marvelous story.

Please… does anybody have more details of what really went wrong?

Beause it was build by Tesla Motors, but shhhh!!!! don´t tell it!

Yes, WHY were they out of fuel? Seems like that little question should have been answered before they set out again.

But props to Lt Gallemore, who thought of the sail and made it work. The sea is uncaring and unforgiving, but he beat it.

I think I read it somewhere else, during the last fuel stop their main tanks were filled, but whoever was refueling them forgot to fill the reserve tanks. So their calculations assumed reserve tanks were full, but when they ran out of fuel on the main ones and switched to reserve, they discovered the tanks were empty.

I was wondering that myself. The link at Pigboats.com implies somebody forgot to fill the reserve fuel tank.

Gimli Glider scenario perhaps?

B^)

There was a leak in the fuel tanks. They did not have a reserve. A contributing factor was that they did not have gauges on the fuel tanks to tell them how much fuel was left.

“There are two kinds of ships in the Navy,

submarines, and targets.”

That’s funny. Never heard thst.

An island is a piece of land surrounded by submarines.

From reading the wikipedia article, it sounds like they were able to add to the charge on the batteries by letting the props windmill in the water. Similar to what was done with the German Uboat U505 when it was captured in WW2.

Very interesting

Sorry to be a pendant, but Mare Island isn’t off the coast of California. It’s in the San Francisco Bay. It’s in Vallejo on the far north east shore of San Pablo Bay. – about 20 miles from the Pacific Ocean.

The Farralons are a bad place to sink. Cold water and lots of great whites. Ugh.

Neat hack though.

Yea, I saw that statement, and was left wondering “off the coast?” These days Mare Island isn’t readily recognizable as an island because it’s connected to other landmass via marshland (along which HWY 37 runs).

Oh what a joy …. I can be pedantic by saying you actually mean “pedant” and not “pendant”. Although I suppose if you want to hang around with people who can do grammar …………

“Things looked dire, and like sea captains before and since, Lt. Douglas turned to his chief engineer for solutions.”

Where’s Scotty when you need him? :-D

” With a foresail, a mainsail, and now a mizzen, the R-14 was a three-masted square-rigged sailing vessel, the first and only submarine to be so rigged.”

Pretty light to be moved by sail.

The power required to move a vessel through water scales roughly with the cube of speed. You don’t need much power to make the 2 knots reported, even on a ship displacing several hundred tons. The R-class displaced a little over 500 tons when surfaced, which is about right for a coastal defence type.

For comparison’s sake, HMS Victory displaces 3500 tons.

Such an awesome story. Surprised nobody has turned it into a movie/series at this point. Somebody should tell Netflix to get on it.

Agree, it´s just good for netflix…

But they need something that viewers won’t go “my kid could have thought of that”

Flight of the Phoenix?

Sail of the Portuguese Man’o’war…

The Navy, at least the U.S. Navy, teaches sailors to, for lack of a better term “think outside the box”. Sailors, particularly engineering rates are taught to use whatever is available and will get the job done. When the USS Samuel B. Roberts hit a mine in the Persian Gulf in 1988 the crew kept the ship from braking in two by wrapping cables around the superstructure.

Amen brother. When your out in the middle of nowhere literally with ocean as far as the eye and radar can you get real creative real quick. I had to fix a radar antenna once with CCOL plastic cover sheets, duct tape, and caulk because our ship parked in a Cockatoo flight path in Australia and the damn birds pecked the fiberglass front off of the antenna. I still despise those birds to this day.

The things you will come up with when you need to get underway.

Wow, that’s interesting. So was the distress signal actually received, even if they never received confirmation?

I was on the USS Cusk SS-348 as my first boat after sub school. I always thought they were called Pig boats was because when underway only wipe down.the cooks and mess cooks could shower. The rest of us had to just wipe down.

If you want to know how to do just about anything, just get hold of the British Admiralty Manuals of Seamanship.

I’ll bet the USNavy has something similar.