Although there are some ferries and commercial boats that use a multi-hull design, the most recognizable catamarans by far are those used for sailing. They have a number of advantages over monohull boats including higher stability, shallower draft, more deck space, and often less drag. Of course, these advantages aren’t exclusive to sailboats, and plenty of motorized recreational craft are starting to take advantage of this style as well. It’s also fairly straightforward to remove the sails and add powered locomotion as well, as this electric catamaran demonstrates.

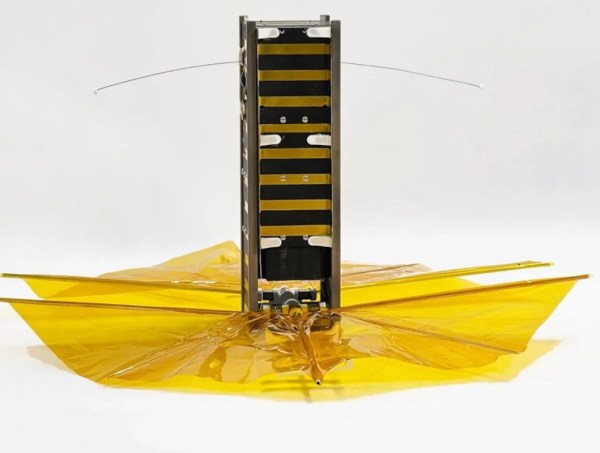

Not only is this catamaran electric, but it’s solar powered as well. With the mast removed, the solar panels can be fitted to a canopy which provides 600 watts of power as well as shade to both passengers. The solar panels charge two 12V 100ah LifePo4 batteries and run a pair of motors. That’s another benefit of using a sailing cat as an electric boat platform: the rudders can be removed and a pair of motors installed without any additional drilling in the hulls, and the boat can be steered with differential thrust, although this boat also makes allowances for pointing the motors in different directions as well.

In addition to a highly polished electric drivetrain, the former sailboat adds some creature comforts as well, replacing the trampoline with a pair of seats and adding an electric hoist to raise and lower the canopy. As energy density goes up and costs come down for solar panels, more and more watercraft are taking advantage of this style of propulsion as well. In the past we’ve seen solar kayaks, solar houseboats, and custom-built catamarans (instead of conversions) as well.

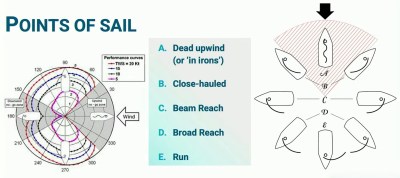

the first sails developed by humans were simple drag devices, sailors eventually developed airfoil sails that allow sailing in directions other than downwind. A

the first sails developed by humans were simple drag devices, sailors eventually developed airfoil sails that allow sailing in directions other than downwind. A