In the fall of 1957, it seemed as though the United States’ space program would never get off the ground. The USSR had launched Sputnik in October, and this cemented their place in history as the first nation in space. If that weren’t bad enough, they put Sputnik 2 into orbit a month later.

By Christmas, things looked even worse. The US had twice tried to launch Navy-designed Vanguard rockets, and both were spectacular failures. It was time to use their ace in the hole: the Redstone rocket, a direct descendant of the V-2s designed during WWII. The only problem was the propellant. It would never get the payload into orbit as-is.

The US Army awarded a contract to North American Aviation (NAA) to find a propellant that would do the job. But there was a catch: it was too late to make any changes to the engine’s design, so they had to work with big limitations. Oh, and the Army needed it two days before yesterday.

The Army sent a Colonel to NAA to deliver the contract, and to personally insist that they put their very best man on the job. And they did. What the Army didn’t count on was that NAA’s best man was actually a woman with no college degree.

The Preschool of Hard Knocks

Mary Sherman Morgan was born November 4, 1921 in the small farming community of Ray, North Dakota. Her parents, Michael and Dorothy Sherman, preferred to keep Mary on the farm doing chores instead of sending her to school. When Mary was eight, a social worker and a sheriff came to the farm to take her to school and get her enrolled.

The one-room elementary schoolhouse was far away and across a river, so the state of North Dakota provided Mary with a horse and riding lessons. The horse, which she named Star, would become a loyal best friend to this poor, unwashed farm girl who owned nothing but two dresses, a corncob doll from her aunt, and a single pair of hand-me-down shoes.

The Sherman family often burned lignite, the cheapest and most toxic form of coal, to keep warm. Mary was fascinated by this flammable brown rock, and this ignited her love of chemistry. She was an excellent student and studied every moment she could, including the horse ride to and from school. Mary often talked to Star about her lessons because she had no one else to talk to. Her parents were completely unsupportive of her education. They didn’t care if she got her homework done, as long as she did it after a full day’s worth of chores. But Mary seized on the value of her education, did the schoolwork, and it paid off.

An Explosive Career Move

Mary graduated from Ray’s high school in 1940 as class valedictorian. Not surprisingly, she had no desire to go back to her life on the farm. So one night she rode Star over the prairie to the town’s diner, where she caught a bus to Toledo, Ohio in the early morning hours. Once there, Mary attended DeSales College on scholarship money she’d received from both the Ray PTA, and the college itself. But after a couple of years, the money was running out.

It was around this time that Mary was approached by a head hunter who offered her a mysterious job that required top secret clearance. He told her she’d be doing “a little of this, a little of that”. Taking the job would mean an immediate position in her field, but she would have to drop out of college.

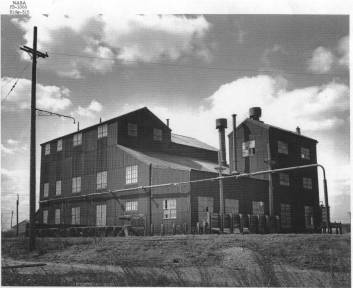

It turned out the job was at Plum Brook Ordnance Works, in a building so hastily-constructed that it sometimes snowed indoors. Plum Brook produced massive quantities of TNT, gunpowder, and various other explosives for the war. Mary’s title was Chemist, and her job was to test barrels of nitric acid for purity. Four years later, the war was over and she was out of a job. But she’d seen the writing on the wall, and bought a typewriter from a pawn shop for writing her résumé.

900 Ties and a Single Skirt

In 1947, Mary moved to California and applied at North American Aviation, an aerospace manufacturer in Inglewood. The hiring manager, Tom Meyers, was desperate to fill positions that required a balance of chemistry and math. The ideal candidate would also have some real-world experience. Although Mary had no college degree, Tom took a chance because of her time at Plum Brook; the place had a reputation as the best munitions plant in America.

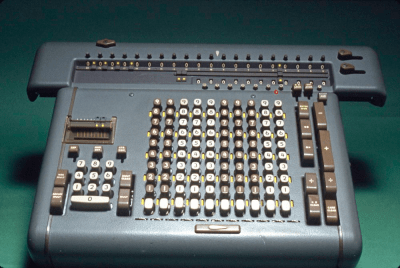

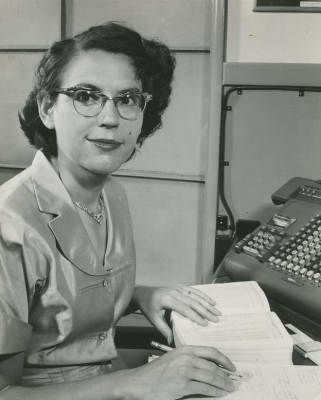

Mary was hired as a Theoretical Performance Specialist. Her job was basically doing math all day long—calculating the expected performance of a rocket fuel when used with a given engine. She sat at a desk in a huge room full of desks, and all 900 of the other desks had men sitting at them. By the time she retired from NAA to raise her children, the company had a dozen female engineers.

Mary was well-liked at North American Aviation and played bridge every day at lunch with some of the other engineers. One of them, a tall redheaded new hire, caught Mary’s eye. She had Tom introduce them. Six months later, she was Mrs. Richard Morgan.

Rockets in Germany’s Pockets

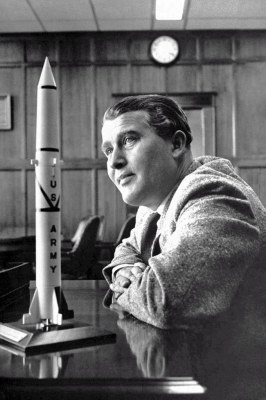

When Germany surrendered to the Allies, the SS ordered that all the books, charts, and records related to rocketry be destroyed so the Allies couldn’t get their hands on the advanced technology. Wernher von Braun and General Walter Dornberger disobeyed the order, with Dornberger forging enough paperwork to get several tons of these documents shipped to a underground fortress on the country’s dime.

After the war, the US secretly brought over about 1600 Nazi rocket scientists including von Braun, and stashed them down at White Sands, away from the media. As part of this program, the DoD contracted North American Aviation to study the V-2 rocket and adapt it to US standards. NAA later built the booster for its successor, the Redstone. Despite the influx of rocket expertise, it wouldn’t be enough to get Redstone into orbit until Mary and her team became involved in inventing a new fuel formulation for the rocket.

Losing Face in the Space Race

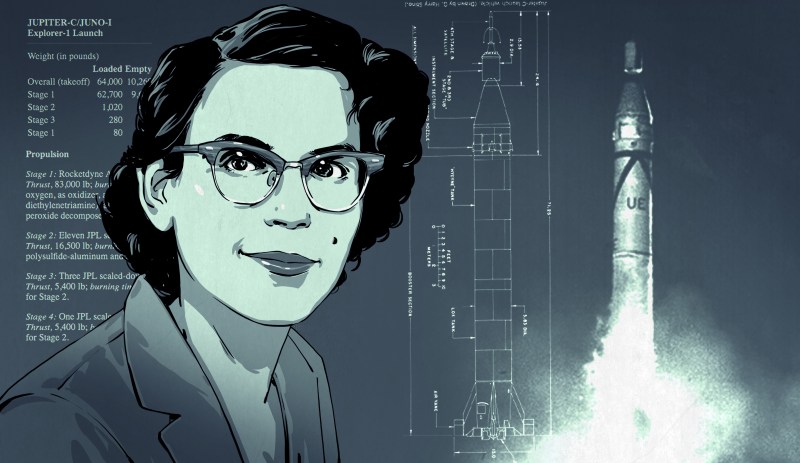

After the Vanguard failures in December 1957, the US turned to Wernher von Braun and his Redstone. But there was a problem. As designed, it didn’t have enough lifting capacity to reach orbit. The Army awarded a contract to North American Aviation to design a better combination of fuel and oxidizer for the main stage of the rocket. This propellant would have to get them the lift they needed without changing the engine’s design.

The Army insisted that NAA put their very best man on the project. So when a colonel showed up in Tom’s office with news of the contract, he gave Mary’s name without hesitation. The colonel strongly objected, because she had no college degree and also happened to be a woman. But Tom insisted that if anyone could save the space program, it would be Mary.

Top-Secret Guesswork

Mary was given two assistants to help with the calculations. Bill Webber and Toru Shimizu had just graduated with master’s degrees in chemical engineering and were hired at a career fair. The three worked night and day doing the only thing they could: make educated guesses about what combinations would work, and then do the math to prove the results.

The Army and NAA had told Mary and her team to find an alternative to liquid oxygen (LOX). But she knew that there was a much better chance of finding an alternative for the fuel side instead. Mary knew there were hundreds of fuel combinations, but few options for oxidizers.

The team considered and discarded many fuels over the next few weeks, including unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine (UDMH). It was ideal, except for its low density rating. But time and again Mary kept coming back to UDMH, and decided to explore mixing it with another fuel that would increase the density.

Eureka!

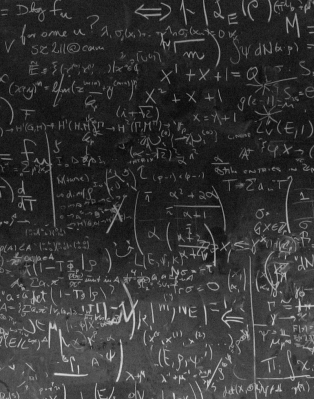

The next day, Bill and Toru came in to find Mary at the chalkboard, mumbling a five-digit number over and over again. It was the density rating of a chemical that one of many reps had given her a brochure about over the years. They found the brochure, and after running the numbers, Mary ordered four tons of diethylenetriamine (DETA) without even consulting Tom.

It looked like they had found the ideal mixer for their cocktail. All they had left to do was find the right ratio, which didn’t take long. Mary guessed it would be 60/40 UDMH/DETA, and the math proved her right. The higher-ups were confident enough in the propellant to test-fire a Redstone A-7 with it right away. Mary wanted to name the new fuel Bagel, since it was served to the rocket with LOX. But the Army named it Hydyne instead.

They needed to show an 8% increase in performance at minimum, and the engine would have to keep going for 155 seconds in three separate tests. It didn’t happen right away, so they kept making guesses. One day they made a slight change to the way the propellant was fed into the engine and mixed together. This was the ticket: the rocket fired up perfectly and burned for the requisite 155 seconds. After repeating the results two more times, it was time to celebrate. On January 31st, 19571958, the United States put Explorer I into orbit.

Her Name Was Mary Sherman Morgan

Soon after the launch, Mary retired as she had become pregnant with her second child. Her husband continued to work at NAA, which was renamed Rocketdyne. Wernher von Braun’s group is one of many that became NASA. A smoker since leaving for college, Mary died of emphysema on August 4th, 2004.

There are very few photographs of Mary, especially from her childhood. According to her oldest son George, who wrote a play and then a book about her life, she worked hard to erase her own history as soon as it was behind her. Couple that with sealed government records, and you have a scientific heroine whose name was almost lost to history forever. Although Mary may not have cared much what you think of her, she certainly deserves our admiration.

Thanks for the tip, [Mbc].

What happened to the horse?

She tied Star up at the diner and left a note bequeathing him to the diner owner’s daughter.

I would love it if you could post some a reference for that story.

It’s in chapter seven of Rocket Girl, the biography written by her oldest son.

Thanks. I found the audiobook and will be listening later today.

I think Star appeared on the menu for the next week as “prime beef”.

I think it was in 1984, the valedictorian of Ray High School bought every girl in the Senior class a rose.

IIRC, it was 13 roses.

My high school electronics teacher had taught at Ray High School before moving to my hometown.

He worked as an Electronics Tech for the military when they tested A-bombs in the South Pacific.

What an inspiring story – thanks for posting it. John

Glad you enjoyed it!

Agreed. These stories are one of the best aspects of Hackaday

ditto – love these stories

“Mary was fascinated by this flammable brown rock…”

Lignite is a soft coal, rock it is not.

Whether you call Lignite a soft coal or a soft rock depends on a number of factors.

Whichever term you choose, it is unlikely to hinder communication, except for those allergic to imprecise use of terms, those unfortunates may die.

Warning: This comment may contain imprecision, errors and/or exaggerations.

Ren, I think you missed the article. :)

I grew up in North Dakota, and have crumbled Lignite in my hands a number of times.

And [John Spencer] you are correct, as talc is considered a “rock”.

I didn’t “miss (the purpose of)” the article [Elliot], but when it hit so close to “home” it became “personal”.

B^)

I visited a co-workers in-laws, on their ranch south of Ray, a couple of times, and, no, their name wasn’t Sherman. B^)

Incorrect.

From Wikipedia :

“Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock”.

So if coal is a rock, and lignite is a coal, what is lignite?

And the Explorer 1 they showed, and the original that spent 90 days in orbit, wore a Bulova watch to work. It used a prototype to the Accutron Watch for its work. That canned timer as it happens was the idea behind the iButtons that (then) Dallas Semiconductor sold or gave them away for samples. In fact I have a bundle of them here. Good explanation behind the stuff that the Redstone used, incidentally the launcher for the Explorer was called Jupiter.

Tom: “Whatca cooking up honey?”

Mary: “unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine & diethylenetriamine.”

Tom: “Couldn’t we just have hamburger?”

Why isn’t this incredible woman talked about nor given her much earned accolades? She was a true pioneer in the rocket fuel development. And on top of it all she never even finished college. There should be a bust or a building named in her memory.

Actually what there really ought to be is a movie. I’m trying to find a producer or studio to make it — but so far no luck.

I love learning about all these women in early tech!

Looks like the Explorer launch date near the end of the article has a typo, it should be 1958 instead of 1957.

Fixed. Thanks.

The only reason that I recognized UDMH is that I read the excellent and out of print book “Ignition!: An Informal History of Liquid Rocket Propellants” which is worth a read.

It’s available on Audible.

Luckily it is/was also available as pdf or ebook download. I much more prefer to read than to listen.

I also enjoyed reading “The Green Flame” by Andrew Dequasie. It’s a non-fiction account of a classified US government project to make high energy fuels based on boron. These materials were toxic, explosive, and spontaneously combustible.

This would make a really good movie, except Hollywood would have to muck it up a bunch like they did with “Hidden Figures”. Doesn’t matter how interesting the real story is, the movie biz *has* to change things.

Oh jeebz. Yeah, “Hidden Figures” was a mess. It was like the writers, whose research consisted solely of watching 1950s movies, just wrote what they thought it “must” have been like, for a black woman working in the white man’s world. If someone were to write a screenplay about this remarkable woman, they would probably have her climbing on the rocket, seconds before launch, to remove a Russian mine from the payload.

Well, I would think that you also wouldn’t really now what it was like as a black woman working at NASA in those days?

No, I certainly DON’T know what it was like to be a black woman at NASA. I also didn’t write a movie about it. And people who were there say the movie was just plain wrong, in many ways.

I read the book – it was quite interesting and based on firsthand interviews with the people involved. I haven’t seen the movie, though, so I’m not quite sure how badly it went.

I’ve already written the screenplay, and no — there is no such scene. :-)

Well, I’m glad to year that.

And who says Hollywood won’t feel the need to mess with your screenplay, George?

There are a million ‘my screenplay’ jokes already.

Don’t need to make another.

All are apt.

From time to time, I like to muse on the casting of (as far as I know) unmade Hollywood movies.

For instance, in the “Green Acres” movie, I can see

Ben Stiller – Mr. Douglas

Gweneth Paltrow – Mrs. Douglas

Will Ferrell – Ebb

Drew Carey – Mr. Haney

Jim Carey – Mr. Kimble

Ellen deGeneres – Ralph

“After the war, the US secretly brought over about 1600 Nazi rocket scientists including von Braun, and stashed them down at White Sands, away from the media.”

Today that would be called unamerican. Good thing it happened back in the 1940’s and 1950’s.

Well, if they had just left them there, the Soviets would have scooped them up.

In the not too distant past, when the USSR collapsed, a lot of their nuclear scientists ended up in rogue countries looking for work.

America paid for Russia’s space program for years largely to keep the rocket scientists off the market.

Thank you for the continuing series of articles on female scientists. I have enjoyed every one of them and hope that they inspire more young women to pursue their dreams.

Explorer I was launched on 31 January 1958, not 1957. Contrary to what this article suggests, Hydyne was not developed after the Sputnik launch; it was tested nearly a year before Sputnik, on 29 Nov 1956. See https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a434109.pdf, page 60.

Interesting article, but very sloppy with the facts.

Speaking of Rocket Fuel…

I recommend “Ignition! An Informal History of Liquid Rocket Propellants” by John D. Clark (Foreword by Isaac Asimov)

This is a reprint of a book Mr. Clark wrote after retirement in the 70’s.

Clark was at the top of the frantic US experimentation with rocket fuels and propellants in the 40’s and 50’s. He worked for the U.S. Naval Air Rocket Test Station and the Liquid Rocket Propulsion Laboratory of Picatinny Arsenal He writes with authority – he was there and in charge of important parts of the melee. Yet he has the wry sense of humor of an accomplished engineer. And what a scene he writes about!

As Asimov says in the foreword, “Now it is clear that anyone working with rocket fuels is outstandingly mad. I don’t mean garden-variety crazy or a merely raving lunatic. I mean a record-shattering exponent of far-out insanity.”

Scott Manly covers this book on his YouTube channel, “The Most Dangerous Rocket Fuels Ever Tested.”

https://youtu.be/_wLk2j7_KB0

“Ignition!” is on the Hackaday virtual bookshelf.

https://hackaday.com/2017/08/11/books-you-should-read-ignition/

Thanks! To both you and Hackaday. It’s also been reprinted and Amazon has it, but Hackaday’s price is better.

As for how insane rocket scientists (err, chemists) are, consider that Dr. Clark relates in this book how he once considered using Dimethyl Mercury as a rocket fuel, but couldn’t find a distributor who was willing to supply the quantity needed for a test. For those of you who do not know about Dimethyl Mercury, look up the case of Karen Wetterhahn, who, at the time, was one of the leading heavy-metal toxicologists in the world, and consider her fate.

The illustration for the article had me wracking my brain as to who she looks like. Then it clicked.

If they wanted to make a movie of her life, Hayley Atwell would make an excellent choice.

The photo reminded me of a former girlfriend, (without Hayley Atwell’s assets).

Found the story very interesting. Sort of reminds me of a joke I made about Ford Motor Company. Or maybe it’s more pathetic than funny.

To wit; I often wonder if Henry Ford with his rather rustic education showed up on the doorstep of Ford Motor Company, would they even seriously consider hiring hm?

Some of these folks were probably very high IQ but probably never tested for it in their lives

I’m going to have to try to read more of your stories of educated women. Stories like these never seem to make it into the “womens’ lib“ screed

Check out our biography series (https://hackaday.com/category/biography/).

It’s not exclusive to women, but we’re trying to select folks you might have heard about before.

Glad you like!

Your comment demonstrates a lack of self-awareness, a large amount of butthurt resentment, ample amounts of motivated reasoning and a lot of faulty logic.

But maybe, just maybe, you can lift your head above the foul muck floor you inhabit. I’ll try to give you a boost: Survivorship Bias.

The rest is up to you!

You are–of course–welcome to have your own personal opinion. I won’t engage with you as your response makes me doubt that you would be open to an open, polite conversation.

One piece of advice I would give you, though: when disputing what someone says, evidence and civility are necessary for you to be taken seriously; just screaming “YOU’RE WRONG, IDIOT!” will tend to either invite a counterattack or simply lead the other to ignore you as an ignorant jerk. As you are a stranger who insulted and maligned me without anything to back up what you have said, I’m taking the latter course. That’s unfortunate, as I generally enjoy discussions on controversial topics; I can learn (and sometimes teach) a lot.

Oh I never meant to imply my interest was only in the great achievers of the female gender. But a lot of them do not seem to have allowed due recognition. The stories of the many obstacles they faced and somehow overcame are fully as interesting as their professional work

Correction: Meant to say “to have been allowed due recognition”. Oopsy