Now is an amazing time to be involved in the hobby electronics scene. There are robots to build, cheap microcontrollers which are easy to program, and computers themselves are able to be found for very low prices. That wasn’t the case in the 1960s though, where anyone interested in “electronics” might have had a few books about ham radios or some basic circuits. If you were lucky though, you may have found a book from 1968 that outlined the construction of a digital computer made out of paperclips that [Mike Gardi] is hoping to replicate.

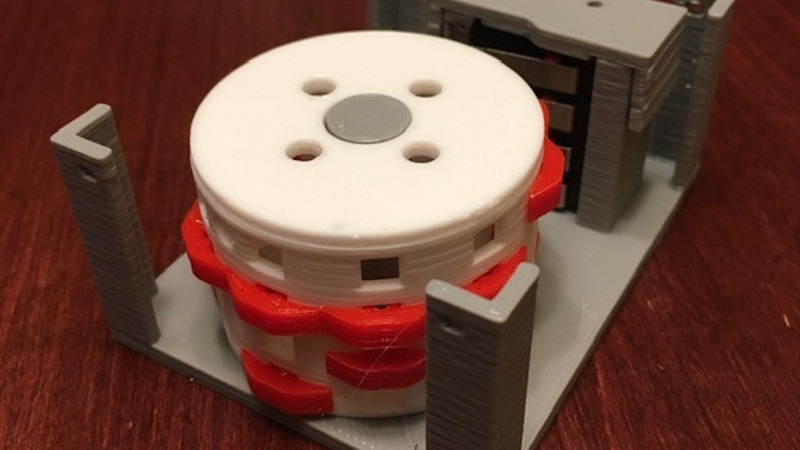

One of the first components that the book outlines is building an encoder, which can convert a decimal number to binary. In the original book the switches were made from paper clips and common household parts, but [Mike] is using a more reliable switch and some 3D prints to build his. The key of the build is the encoder wheel and pegs, which act as the “converter” between decimal and binary and actually performs the switching.

It’s a fairly straightforward build, but by working through the rest of the book the next steps are to build two binary encoders and hook all of them up to an ALU which will give him most of a working computer from long lost 1960s lore. He’s been featured recently for building other computers from this era as well.

Thanks to [DancesWithRobots] for the tip!

That book teaches how computers work. I head that book for over 40 years. I thought updating to LEDs would be a great improvement, but 3d printing is another good improvement.

Stay tuned. The rest of the build will involve relays and 7400 series integrated circuits ;-)

The book describes how to build a BCD or Binary Coded Decimal switch as part of the complete project. IMHO that’s the neatest, most useful part of it. If you have a need for a BCD switch but don’t happen to *have* a BCD switch, this book shows you how to “stone knives and bearskins” one. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F226oWBHvvI

What the finished setup actually is, is like a fancy abacus. It does nothing automatically, it leads the operator somewhat through manually operating a few analogs of core components of a computer.

To make it a true computer it would need a bunch of solenoids to throw switches, motors to turn knobs etc. It would have to automatically flip the switches in the “memory” section as the program drum is turned instead of simply turning on some lamps to prompt the operator which switches (bent pieces of paperclip in the book) to open or close.

Years ago, when I first heard about this book and downloaded a copy, I was seriously thinking of building one as a fun project. But after reading the book and discovering *it’s not really a computer* I changed my mind.

There was a company that based a commercial device on the design, with real switches etc in place of all the bent up paperclips. It was sold as an instructional device to teach people the very lowest level workings of digital computers. The design can still do that, but any problem it can be used to work would likely be far faster to compute with a pencil and paper.

It still is a fun project IMHO. I’ve been building a lot of these “not really a computer” projects lately and I’m having a great time doing it.

Nice work. I also like your rotary switch.

Kudos for the Star Trek: City on the Edge of Forever reference. :)

–Greg

https://hackaday.com/2015/10/19/diy-computer-1968-style/

That was a fantastic article. I enjoyed re-reading it.

If you are interested in this project you can follow my progress on Hackaday.io: https://hackaday.io/project/168833-wdc-1-a-working-digital-computer

Is cool but BCD encoded thumbwheels are still available. A full blown Digital ALU would be cool but serious endeavor. Analog computational cheats withstanding. Like Gregg Eshelman said lots of motors and relays.

I have a copy of that book. I built a little of the machine and I learned to count to 1023 on my fingers while reading it. :-)