The fortunate among us may very well have a bit of time off from work coming up, and while most of that time will likely be filled with family obligations and festivities, there’s probably going to be some downtime. And if you should happen to find yourself with a half hour free, you might want to check out the Clickspring Byzantine Calendar-Sundial mega edit. And we’ll gladly accept your gratitude in advance.

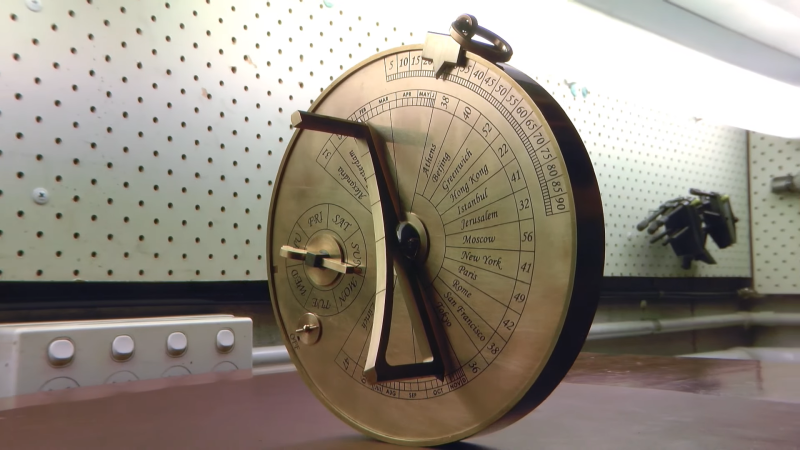

Fans of machining videos will no doubt already be familiar with Clickspring, aka [Chris], the amateur horologist who, through a combination of amazing craftsmanship and top-notch production values, managed to make clockmaking a spectator sport. We first caught the Clickspring bug with his open-frame clock build, which ended up as a legitimate work of art. [Chris] then undertook two builds at once: a reproduction of the famous Antikythera mechanism, and the calendar-sundial seen in the video below.

The cut condenses 1,000 hours of machining, turning, casting, heat-treating, and even hand-engraving of brass and steel into an incredibly relaxing video. There’s no narration, no exposition — nothing but the sounds of metal being shaped into dozens of parts that eventually fit perfectly together into an instrument worthy of a prince of Byzantium. This video really whets our appetite for more Antikythera build details, but we understand that [Chris] has been busy lately, so we’ll be patient.

Absolutely stunning work.

Beautiful! Half an hour watching well spent.

Does anyone know what is that treatment he does to the screws that makes them turn almost black?

he just heats them up. if you look at his video collection, there’s one where he explains it; i think it’s part of the clock build. yeah, here’s the one: https://youtu.be/5sAw4Q1PM8Y?list=PLZioPDnFPNsETq9h35dgQq80Ryx-beOli

It’s called heat bluing.

1st he hardens them by heating cherry red and quenching in oil, then he cleans them off and probably re polishes them and then he heats them over a pile of brass shavings with an alcohol lamp to evenly distribute the heat. The color change you see happening is a chemical reaction with the clean surface of polished steel forming an oxide layer as the surface is heated.

Heat bluing can be done to any steel component, but doing it after hardening- he’s actually tempering the screws- heating them up to a specific point to lower the hardness an exact amount- and that color change will always repeat for the same amount of heat the object absorbs, so when you are tempering that oxide cour actually is like a thermometer that tells you how hot you have gotten the entire piece of Steel. It lets you know in this case how much you have allowed the part to temper, aka soften back, from glass hard condition.

The actual oxide forming will happen even to a completely soft piece of Steel as long as it is polished clean, and you can polish it off if you don’t want to see the color after it is tempered to a specific hardness, but yeah what you are seeing is a chemical reaction just from sticking polished steel under consistent Heat in the open air.

You can try it yourself with a little brass pan full of brass shavings or quartz sand (what I used in watchmaking school), anything that allows the heat of a small alcohol lamp to transfer through. If you want to get an exact solid shade of color like he does you need to be extremely patient and do it slowly- the color change happens fast if under direct flame. You can do it with an carbon steel easiest, but other ferrous metals can react similarly if you try.

I myself have even done this with some polished etched nickle iron meteorite slices cut into star shapes for a girlfriend’s earrings. They had a rainbow of colors. Anything with iron with form an oxide layer if heated like this.

Interesting, I came across bluing in another context a couple of weeks ago. Not real fresh in the memory, but the discussion was crystal radio detectors and point contact diode type arrangements. It was said that razor blades worked if they were blued.. I assume they’d be heat blued at the factory.. and a hard oxide layer seems to make sense. As I’m thinking now it was a letters column discussion in a 1980s mag about an article I don’t have. I think they were talking about point contact to a galena crystal with the blade. Anyhoo… at this point in time blued razor blades had become hard to find. It was suggested that they hit up a sporting goods or gunsmith for gun bluing or rifle bluing “and follow the directions”… I am assuming that that bluing process probably doesn’t do the depth of hardening that that heat process does and maybe only uses an acid to just make a hard oxide on the surface???

However, your process sounds like something to try for point contact diode purposes, since one could treat razor blades, sewing needles, sharpened up screws with fine thread and like artifacts.

Would anyone happen to know though if drywall screws are treated in this way? They’re black, seem to be of a hardened type of steel, and snap rather than yield, also some are quite sharp or have edges. Ergo a potential common household object for experimentation with point contact semiconductors.

I managed to make a functional point-contact diode using a box cutter blade that I had blued at one end with a handheld lighter. It worked well as the “crystal” in my crystal radio project a few years ago.

I suspect that unless you need a very specific oxide layer makeup, simply heating the metal might work for you.

>that color change will always repeat for the same amount of heat the object absorbs

Not quite. It’s a chemical reaction – time is a factor, availability of oxygen is a factor, and it’s not a perfectly linear relationship, so you can’t directly count it in kelvin-seconds.

Following the color of the part gets you in the ballpark, but it is not exact unless you keep all the other variables constant.