Fair warning for readers with a weak stomach, the video below graphically depicts an innocent rubber band airplane being obliterated in mid-air by a smug high-tech RC helicopter. It’s a shocking display of airborne class warfare, but the story does have a happy ending, as [Concrete Dog] was able to repair his old school flyer with some very modern technology: a set of 3D printed propeller blades.

Now under normal circumstances, 3D printed propellers are a dicey prospect. To avoid being torn apart by the incredible rotational forces they will be subjected to, they generally need to be bulked up to the point that they become too heavy, and performance suffers. The stepped outer surface of the printed blade doesn’t help, either.

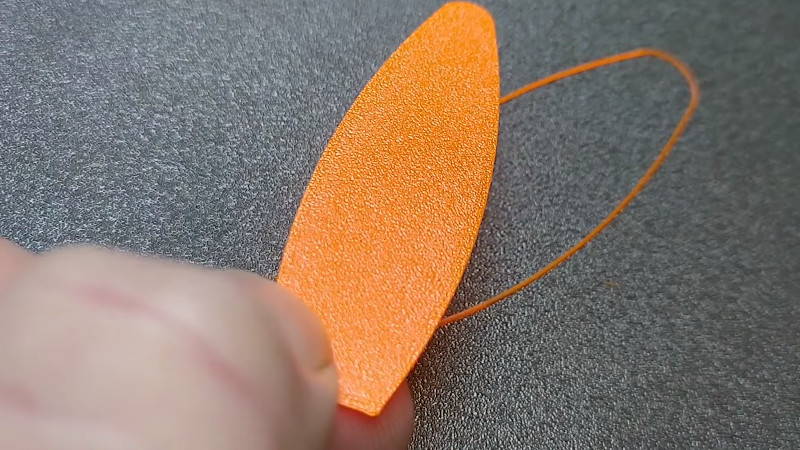

But in a lightweight aircraft powered by a rubber band, obviously things are a bit more relaxed. The thin blades [Concrete Dog] produced on his Prusa Mini appear to be just a layer or two thick, and were printed flat on the bed. He then attached them to the side of a jar using Kapton tape, and put them in the oven to anneal for about 10 minutes. This not only strengthened the printed blades, but put a permanent curve into them.

But in a lightweight aircraft powered by a rubber band, obviously things are a bit more relaxed. The thin blades [Concrete Dog] produced on his Prusa Mini appear to be just a layer or two thick, and were printed flat on the bed. He then attached them to the side of a jar using Kapton tape, and put them in the oven to anneal for about 10 minutes. This not only strengthened the printed blades, but put a permanent curve into them.

The results demonstrated at the end of the video are quite impressive. [Concrete Dog] says the new blades actually outperform the originals aluminum blades, so he’s has to trim the plane out again for the increased thrust. Hopefully the extra performance will help his spindly bird avoid future aerial altercations.

On the electrically powered side of things, folks have been trying to 3D print airplane and quadcopter propellers for almost as long as desktop 3D printers have been on the market. With modern materials and high-resolution printers the idea is more practical than ever, though it’s noted they don’t suffer crashes very well.

Indoor free flight prop blades are usually made of built up balsa strips covered in clear plastic. As are the planes themselves. Props are relatively large, slow turning things.

They are not very stressed.

It’s a very old competition field. Owned by wily old men. Record indoor rubber band free flight time is over an hour.

This whole aircraft is an obvious fat old pig. The roof struts make the venue an obvious bad choice as well. I bet they left the ventilation on too (verboten or they would just design the plane to circle in the updraft).

Not to discourage too much, not a bad first effort.

Don’t let your friends see you with the big one, they will laugh at you. Like a moped. Fun to ride…

My understanding is the ‘best’ indoor ones are still made up of super thin ‘micofilm’ * wrapped around the lightest framing possible – so thin stiff (Aluminium?) wires for both the prop and wings… At least if pure flight time is the only goal.

However I’d argue this is a better choice, as you can actually touch it without breaking it – its properly flyable and actually fixable too. The ‘microfilm’ wire frame style but with off the shelf thin plastics seems to be a common modern variation for longest flight criteria, but from what I can tell it is still substantially heavier for only a little more durability. Not something I’ve any interest in actually getting hands on with, something that delicate isn’t my cup of tea.

*seems to be thin film of laquer/varnish mixed with a light vegetable oil type stuff float on water to get stupidly stupidly thin films method – the guide I read was actually using the the thin film effect on its colour to tell you if your wing was going to be too heavy!

HaD did an article about free flight rubber band airplanes a bit ago. I can’t find the article though. I vaguely recall it was about some guy’s massive airplane going for duration aloft record and he was in, like, the low minutes range. There were a bizarre contingent of commenters that refused to believe the record was an hour or so.

That’s fun!

In impressed with what a tough time the helicopter had lining up that crash.