If you search the Internet for “Clone Wars,” you’ll get a lot of Star Wars-related pages. But the original Clone Wars took place a long time ago in a galaxy much nearer to ours, and it has a lot to do with the computer you are probably using right now to read this. (Well, unless it is a Mac, something ARM-based, or an old retro-rig. I did say probably!)

IBM is a name that, for many years, was synonymous with computers, especially big mainframe computers. However, it didn’t start out that way. IBM originally made mechanical calculators and tabulating machines. That changed in 1952 with the IBM 701, IBM’s first computer that you’d recognize as a computer.

If you weren’t there, it is hard to understand how IBM dominated the computer market in the 1960s and 1970s. Sure, there were others like Univac, Honeywell, and Burroughs. But especially in the United States, IBM was the biggest fish in the pond. At one point, the computer market’s estimated worth was a bit more than $11 billion, and IBM’s five biggest competitors accounted for about $2 billion, with almost all of the rest going to IBM.

So it was somewhat surprising that IBM didn’t roll out the personal computer first, or at least very early. Even companies that made “small” computers for the day, like Digital Equipment Corporation or Data General, weren’t really expecting the truly personal computer. That push came from companies no one had heard of at the time, like MITS, SWTP, IMSAI, and Commodore.

The IBM PC

The story — and this is another story — goes that IBM spun up a team to make the IBM PC, expecting it to sell very little and use up some old keyboards previously earmarked for a failed word processor project. Instead, when the IBM PC showed up in 1981, it was a surprise hit. By 1983, there was the “XT” which was a PC with some extras, including a hard drive. In 1984, the “AT” showed up with a (gasp!) 16-bit 80286.

The personal computer market had been healthy but small. Now the PC was selling huge volumes, perhaps thanks to commercials like the one below, and decimating other companies in the market. Naturally, others wanted a piece of the pie.

Send in the Clones

Anyone could make a PC-like computer, because IBM had used off-the-shelf parts for nearly everything. There were two things that really set the PC/XT/AT family apart. First, there was a bus for plugging in cards with video outputs, serial ports, memory, and other peripherals. You could start a fine business just making add-on cards, and IBM gave you all the details. This wasn’t unlike the S-100 bus created by the Altair, but the volume of PC-class machines far outstripped the S-100 market very quickly.

In reality, there were really two buses. The PC/XT had an 8-bit bus, later named the ISA bus. The AT added an extra connector for the extra bits. You could plug an 8-bit card into part of a 16-bit slot. You probably couldn’t plug a 16-bit card into an 8-bit slot, though, unless it was made to work that way.

The other thing you needed to create a working PC was the BIOS — a ROM chip that handled starting the system with all the I/O devices set up and loading an operating system: MS-DOS, CP/M-86, or, later, OS/2.

Protection

IBM didn’t think the PC would amount to much so they didn’t do anything to hide or protect the bus, in contrast to Apple, which had patents on key parts of its computer. They did, however, have a copyright on the BIOS. In theory, creating a clone IBM PC would require the design of an Intel-CPU motherboard with memory and I/O devices at the right addresses, a compatible bus, and a compatible BIOS chip.

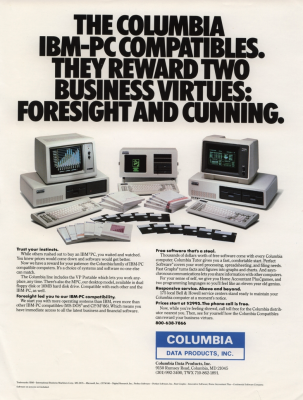

But IBM gave the world enough documentation to write software for the machine and to make plug-in cards. So, figuring out the other side of it wasn’t particularly difficult. Probably the first clone maker was Columbia Data Products in 1982, although they were perceived to have compatibility and quality issues. (They are still around as a software company.)

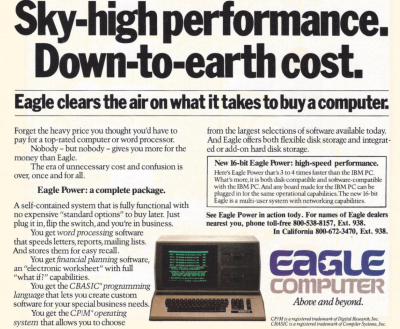

Eagle Computer was another early player that originally made CP/M computers. Their computers were not exact clones, but they were the first to use a true 16-bit CPU and the first to have hard drives. There were some compatibility issues with Eagle versus a “true” PC. You can hear their unusual story in the video below.

One of the first companies to find real success cloning the PC was Compaq Computers, formed by some former Texas Instruments employees who were, at first, going to open Mexican restaurants, but decided computers would be better. Unlike some future clone makers, Compaq was dedicated to building better computers, not cheaper.

Compaq’s first entry into the market was a “luggable” (think of a laptop with a real CRT in a suitcase that only ran when plugged into the wall; see the video below). They reportedly spent $1,000,000 to duplicate the IBM BIOS without peeking inside (which would have caused legal problems). However, it is possible that some clone makers simply copied the IBM BIOS directly or indirectly. This was particularly easy because IBM included the BIOS source code in an appendix of the PC’s technical reference manual.

Between 1982 and 1983, Compaq, Columbia Data Products, Eagle Computers, Leading Edge, and Kaypro all threw their hats into the ring. Part of what made this sustainable over the long term was Phoenix Technologies.

Rise of the Phoenix

Phoenix was a software producer that realized the value of having a non-IBM BIOS. They put together a team to study the BIOS using only public documentation. They produced a specification and handed it to another programmer. That programmer then produced a “clean room” piece of code that did the same things as the BIOS.

This was important because, inevitably, IBM sued Phoenix but lost, as they were able to provide credible documentation that they didn’t copy IBM’s code. They were ready to license their BIOS in 1984, and companies like Hewlett-Packard, Tandy, and AT&T were happy to pay the $290,000 license fee. That fee also included insurance from The Hartford to indemnify against any copyright-infringement lawsuits.

Clones were attractive because they were often far cheaper than a “real” PC. They would also often feature innovations. For example, almost all clones had a “turbo” mode to increase the clock speed a little. Many had ports or other features as standard that a PC had to pay extra for (and consume card slots). Compaq, Columbia, and Kaypro made luggable PCs. In addition, supply didn’t always match demand. Dealers often could sell more PCs than they could get in stock, and the clones offered them a way to close more business.

Issues

Not all clone makers got everything right. It wasn’t odd for a strange machine to have different interrupt handling than an IBM machine or different timers. Another favorite place to err involved AT/PC compatibility.

In a base-model IBM PC, the address bus only went from A0 to A19. So if you hit address (hex) FFFFF+1, it would wrap around to 00000. Memory being at a premium, apparently, some programs depended on that behavior.

With the AT, there were more address lines. Rather than breaking backward compatibility, those machines have an “A20 gate.” By default, the A20 line is disabled; you must enable it to use it. However, there were several variations in how that worked.

Intel, for example, had the InBoard/386 that let you plug a 386 into a PC or AT to upgrade it. However, the InBoard A20 gating differed from that of a real AT. Most people never noticed. Software that used the BIOS still worked because the InBoard’s BIOS knew the correct procedure. Most software didn’t care either way. But there was always that one program that would need a fix.

The original PC used some extra logic in the keyboard controller to handle the gate. When CPUs started using cache, the A20 gating was moved into the CPU for many generations. However, around 2013, most CPUs finally gave up on gating A20.

The point is that there were many subtle features on a real IBM computer, and the clone makers didn’t always get it right. If you read ads from those days, they often tout how compatible they are.

Total War!

IBM started a series of legal battles against… well… everybody. Compaq, Corona Data Systems, Handwell, Phoenix, AMD, and anyone who managed to put anything on the market that competed with “big blue” (one of IBM’s nicknames).

IBM didn’t win anything significant, although most companies settled out of court. Then they just used the Phoenix BIOS, which was provably “clean.” So IBM decided to take a different approach.

In 1987, IBM decided they should have paid more attention to the PC design, so they redid it as the PS/2. IBM spent a lot of money telling people how much better the PS/2 was. They had really thought about it this time. So scrap those awful PCs and buy a PS/2 instead.

Of course, the PS/2 wasn’t compatible with anything. It was made to run OS/2. It used the MCA bus, which was incompatible with the ISA bus, and didn’t have many cards available. All of it, of course, was expensive. This time, clone makers had to pay a license fee to IBM to use the new bus, so no more cheap cards, either.

You probably don’t need a business degree to predict how that turned out. The market yawned and continued buying PC “clones” which were now the only game in town if you wanted a PC/XT/AT-style machine, especially since Compaq beat IBM to market with an 80386 PC by about a year.

Not all software was compatible with all clones. But most software would run on anything and, as clones got more prevalent, software got smarter about what to expect. At about the same time, people were thinking more about buying applications and less about the computer they ran on, a trend that had started even earlier, but was continuing to grow. Ordinary people didn’t care what was in the computer as long as it ran their spreadsheet, or accounting program, or whatever it was they were using.

Dozens of companies made something that resembled a PC, including big names like Olivetti, Zenith, Hewlett-Packard, Texas Instruments, Digital Equipment Corporation, and Tandy. Then there were the companies you might remember for other reasons, like Sanyo or TeleVideo. There were also many that simply came and went with little name recognition. Michael Dell started PC Limited in 1984 in his college dorm room, and by 1985, he was selling an $800 turbo PC. A few years later, the name changed to Dell, and now it is a giant in the industry.

Looking Back

It is interesting to play “what if” with this time in history. If IBM had not opened their architecture, they might have made more money. Or, they might have sold 1,000 PCs and lost interest. Then we’d all be using something different. Microsoft retaining the right to sell MS-DOS to other people was also a key enabler.

IBM stayed in the laptop business (ThinkPad) until they sold to Lenovo in 2005. They would also sell them their server business in 2014.

Things have changed, of course. There hasn’t been an ISA card slot on a motherboard in ages. Boot processes are more complex, and there are many BIOS options. Don’t even get us started on EMS and XMS. But at the core, your PC-compatible computer still wakes up and follows the same steps as an old school PC to get started. Like the Ship of Theseus, is it still an “IBM-compatible PC?” If it matters, we think the answer is yes.

If you want to relive those days, we recently saw some new machines sporting 8088s and 80386s. Or, there’s always emulation.

IMSAI, not IMASI. We had one in the “computer lab” in my high school in the late 70’s.

Now get off my lawn.

The disadvantage of touch typing.

This is a good perspective on a portion of the IBM. I lived that era, with microcontrollers in 1976 and was pleased when in 1981 IBM announced their PC. IBM’ers who were on the development team have lots of interesting stories about speed, design trade offs and go-to-market that should be told. What made IBM dominant in the 50s,60s, 70s and 80s was their software and the software architecture that protected the data – PCs had none of this and it took well over a decade before Netware, Microsoft created must-have software solutions such as Novell Netware and Microsoft Outlook that drove adoption.

One of the big reasons that the IBM PC caught on was that businesses started buying them. They knew IBM was a solid company and remembered the motto “Nobody has ever been fired for buying IBM”. Other small computers of the day either looked like home/game systems or someone’s garage project.

Here in Europe the IBM PC was delayed, it wasn’t sold (in quantities) in 1981 but rather from ’83 onwards. Via IBM UK?

Here in Germany, the Sirius 1 (Victor 9000) thus almost became the dominant standard PC and not the IBM PC, which was second.

The Sirius 1 also was more sophisticated, by the way, I think.

Some info:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sirius_Systems_Technology

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A93TmmF3Q3w

Correct.

Very interesting! 😎 The article describes the North American point of view very well, I think. 👍

I just might like to add that there was a first wave (ca. 1984-1987?) of no-name PC clone motherboards from Taiwan, as far as I know.

These boards were able to function with a copy of IBM BIOS or a compatible BIOS.

That means these cheap motherboards were hardware compatible with the real thing and users could equip them as needed.

They were bare-bone motherboards, basically.

With the glue logic installed, but RAM and BIOS/ROM BASIC had to be added.

The CPU probably was included, too, albeit likely not an intel 8088 but a second sourced model.

The best I’ve found so far was this episode of the Computer Chronicles,

but I vaguely remember watching a different episode of a show in which clone motherboards

on a market on street were shown and in which a seller was interviewed about the legal situation..

The Computer Chronicles – Asian Clones (1987)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VLM12igHTX4

Anyway, just saying. It’s perhaps merely interesting to us non-Americans, anyway, since our low-end PCs were not so often brand models made by popular US companies of the time.

Those clone motherboards and expansion cards we had were from all around the globe, rather.

By late 80s or early 90s, cheap Turbo XT boards like that “Juko” board found

its way in our desktop cases, too, sometimes.

In certain parts Europe, a lot of strange PC clone hardware had existed, too.

This is my sense of things: The problem with IBM and their personal computers is that they neither understood their own own creation, nor their customer base.

I was under the impression that, internally, the PC was regarded by many in the organization with derision and disdain. After all, “we’re a mainframe company.” I’ m no IBM historian, but I would guess the closest thing they had to a “personal computer” up to that point might have been something like the Series 1. It’s as though their own leadership regarded the PC project as a toy.

When the PC became successful beyond their wildest dreams, and clone and accessory card makers ate their lunch, they launched the PS2 series. I recall those machines being very nice… typical high-quality IBM.

The problem is those machines didn’t really do anything a contemporary clone couldn’t do for a lot less money, and accessory cards were so encumbered with royalties for the license to Micro Channel that those cards may as well not exist.

Example: I worked at a business that specified IBM for their office computers, and I had direct experience working with various models in the PS2 family. I also remember buying a Micro Channel Hayse modem card for one of those machines that cost 8 times as much the same Hayse model engineered for the ISA bus.

In short, IBM’s first mistake was apathy, its second, greed. In an alternate universe/timeline, where they navigated successfully between those two rocks, IBM would probably be king to this day.

Though the PS/2 did not replace the PC/AT compatibles, it did create the PS/2 port for keyboards and mice, which persists until this day.

Sorry, not intended to be a reply to Observer

Decent coverage of the hardware side of things… The intrigue around the software and OS development is much more interesting — full of bad actors and behaviors. As one of those right in the middle of that action, there is more to the story, to yet be told.

Though electrically, the DIN keyboard interface of PC/AT and PS/2 keyboard interface is same.

The AT keyboard protocol is used by PS/2 keyboards, too.

It’s possible to use passive, mechanical adapters DIN<>PS/2.

What’s new is that a mouse is also handled via keyboard interface, basically.

There are PS/2 keyboard/mouse combo ports on laptops or newer ATX motherboards (half green/pink).

I read ‘core wars’

:-)

Who remember?

Yes, though it was out of my intellectual reach to play it myself. I know it only from an article by A K Dewdney.

“Caution: Your IBM computer may not be 100% clone compatible.”

Yep, I remember those days.

Hah, indeed! 🥲

But seriously, the early PC BIOS revisions weren’t that great. IBM wasn’t great at software.

Things like HDD support or option ROM support were only available in clone BIOSes or later PC/XT BIOSes.

I have an early Commodore PC 10 that was using an early Commodore BIOS that was just as limited as an early IBM PC BIOS.

It couldn’t use EGA/VGA cards because of that, the BIOS was too primitive. An upgrade helped.

IBM PC BIOS was fine, especially considering the fact that it fit in an 8 KiB ROM…

IBM PC didn’t have an HDD, so there wasn’t any reason to include it there. Moreover, there wasn’t an HDD controller standard back in the day, so what hardware exactly it should have supported?

While the initial IBM PC BIOS (dated 04/24/81) didn’t support extension ROMs, fairly soon after the IBM PC release, IBM released an updated BIOS (dated 10/27/82) that supported ROM BIOS extension scan. This implemented a flexible mechanism for adding support for HDD controllers, new graphics adapters (including VGA), network boot option, etc…

The HDD support wasn’t integrated in the BIOS itself until the release of IBM AT.

Thank you for giving me flashbacks to the days of having to manually enter Cylinder/Head/Sector count information & bad block lists into the BIOS for the hard drive, and having to run a command to park the heads before powering off.

The good old days?

Eurgh, now that I have read this I have flashbacks now too… I may have to see my therapist for some PTSD treatment.

Ahem! 🤧

True! Of course not, the ST412/ST506 type of 8-Bit MFM/RLL HDD controllers of their time had their own firmware,

which had a low-level setup routine that could be invoked via Debug on DOS (debug -g=800:5 or something). 🙂

But these old BIOS releases weren’t supporting them yet,

neither the real IBM ones nor those that “faitfully” emulated the ancient PC BIOS because they took it too seriously, as a strict reference.

Their BIOS code wasn’t being loaded, just like EGA/VGA BIOS wasn’t.

Commodore with the PC 5 and PC 10 (original series) was such an negative example.

It took years, until second half of the 80s, that their BIOSes were upgraded to the level of the PC/XT BIOS.

Other companies such as Siemens had BIOSes that detected the presence of an ordinary PC/XT controller at boot-up.

Some printed “FIXED DISK” during POST, in addition to “FPU”, “GAME” or “COLOR GRAPHICS”.

Note that this was about generic HDD controllers, not proprietary models.

They probably recognized the “Western Digital” string in memory or had other means for detection (WD100x controllers were popular).

Meanwhile, the IBM PC BIOS and PC/AT BIOS did print basically no POST messages, just the memory count.

But that’s not my point of criticism, exavtly.

I’m just puzzled by IBM didn’t keep PC and PC/XT in sync.

The later sold PC 5150 could have been equipped with an 5160 BIOS.

Or if the hardware difference was too big: with an modified 5160 BIOS.

Oooohhhh…I remember the debug routine, and then executing ‘g=c800:5′ from witin debug. Debug was a very handy tool for reverse engineering, and even data recovery.

…or removing the cover of an MFM drive (to keep it sort-of cool), and then formatting a 20MB drive to 30MB on a RLL controller… ☺

Most XT machines I remember from the late 80’s had clone BIOS’. I had an ICL Elf (4.77MHz), but I cannot remember what BIOS was fitted to it…too long ago for the grey matter to remember such things.

Hi! The question is, though, if those PC Model 5150 stored in the warehouses or in freighter containers were ever equipped with an upgraded ROM chip afterwards.

If they were, then I wonder why PC 10s sold in Germany of 1985 still were based on an outdated 1981 BIOS code.

Because it would sort of make sense, if “our” Model 5150 were not up to date when their BIOS was analyzed and then used as a blue print or reference for a compatible BIOS.

The need for a HDD has become natural by 1984/1985, after all. Office users did feel like playing disc jokey with 2x 5,25″ 360k drives.

(PS: Sorry for another PC 10 reference, but at one point it simply was a popular clone here.

Units were installed at our postal agency, the train service, offices etc. Commodore aka CBM was a thing, almost like IBM.

Also, I don’t know that many PC/XT models, otherwise I would use other examples too.)

I think it was the PS/2 model 57 that had the worst compatibility. A lot of software used undocumented entry points into the BIOS. IBM only maintained compatibility on the documented interface.

The not complete compatibility of early clones with IBM PC came because of wrong, CP/M-like expectations about programming these computers. To support CP/M-80, computers didn’t have to have full hardware compatibility with a certain machine. The requirements were: 8080 or Z80 CPU, RAM at the bottom of the address space, a console, and a storage device. Applications accessed hardware through the OS, that used a computer specific BIOS, which was patched to add support for 3rd party controllers.

Theoretically, IBM PC and MS-DOS offered the same paradigm, applications could use MS-DOS and BIOS APIs, that would abstract the hardware. Microsoft even offered vendor customizable IO.SYS… But, application programmers pretty soon started accessing the hardware directly, bypassing the BIOS, particularly display controller (BIOS routines were slow) and timer (almost no BIOS support). This resulted in the need of complete IBM PC hardware compatibility…

A20 is an interesting story… You’d thing why in the world applications that typically run in lower 640KiB part of memory would care about the address rollover from 0xFFFFF (ROM BIOS area) to 0x00000 (interrupt table)? There was a single, very specific reason: CP/M compatibility… DOS 1.0 was designed to be CP/M compatible, and CP/M system calls work by calling subroutine at address 5 (CALL 5)… Now addresses 6-7 should have contained the memory size available for the CP/M application. In case of x86, the CALL would become a “CALL NEAR”, that is a call within 64 KiB segment, and without an extra effort it won’t be able to call the DOS system call entry point. So Tim Patterson implemented a clever mechanism utilizing locations 5-9, to implement a “CALL FAR 0000:00C0” using the address wrap-around… The location 0x000C0, which is technically in the interrupt table, contained a JMP FAR to the DOS CP/M compatible system call entry point…

I’m old enough to have seen this in BIOS setup screens. A lot. Never did bother looking up what it actually did. You learn something new every day, even if it is two decades out of date.

It was relevant for CALL5 interface, programs auto-converted from CP/M to DOS.

The address wrap-around helped to simplify the mechanism.

That was in the mid-80s, roughly.

Later DOS applications and DOSes by various vendors did work with either state of A20 Gate.

Almost no application from the 90s does care anymore.

You can still boot MS-DOS 6.x on a modern PC that has the A20 Gate removed, also.

The XMS driver, himem.sys, knows many ways of handling an A20 Gate, also. Over 20, or so.

It’s knowledge is limited to level of knowledge the year ~1994, though.

Later incarnations were shipped with Windows 9x, Caldera DOS, FreeDOS etc.

The A20 Gate and himem.sys are both useful for managing the High Memory Area (HMA), though.

The HMA is that region those 64 KB (minus 16 Bytes) past the first Megabyte.

It’s mostly used by DOS itself, applications don’t use it (except Win/286).

If no HMA is available, DOS loads more code into conventional memory (base memory) instead.

Also, modern DOS applications don’t really use that much conventional memory anymore.

Instead, they use XMS and DPMI API primarily, if they need lots of memory.

“ unless it is a Mac, something ARM-based,…”

So… probably not then? Most websites are >50% mobile use these days – and especially “news” type websites such as HAD, which means Android or iOS on some flavour of ARM. Add into that the Mac and Chromebook usage and I’d not be surprised if Intel-derived architectures were notably a minority.

Turbo button was actually used to LOWER the CPU speed because some games ran way too fast.

It was often used as a brake, yes. But not always. It did depend on the motherboard, really.

Some PC motherboards had an inverted logic (-or normal logic depending on how we look at it-),

which ran in 4,77 MHz mode by default unless two pin headers were shorted by a switch (button pressed).

Very in depth article about pc clones are we going to see further articles on clones of other computers?

Before DOOM ran on everything, Microsoft Flight Simulator was the benchmark program we ran to see how compatible a clone machine was. If it ran without problems then anything else would.

IBM were the computer company so when they shipped a PC it gave the systems instant street cred even though the system capabilities were really no better than the Z80 CP/M systems it competed with. IBM made several missteps, though. The first was shipping their PC with their standard documentation, which in this case was a three ring binder that included full schematics and a BIOS source listing. The second was their licensing agreement with Microsoft which allowed MS to ship MS-DOS — essentially the PC-DOS they’d made for IBM with a logo change — to all comers. Microsoft also provided the ROM BASIC so between the documentation and the MS’s code all you needed to make a clone was a ready supply of parts. IBM eventually cottoned on to what was going on and sent out ‘cease and desist’ letters but being IBM they gave everyone a decent sized window to organize their own BIOS. (IBM-PC hardware was generic and was by this time being altered and improved upon.)

I was recruited by Corona Data Systems in mid-1984 before the BIOS effort became necessary. I was nominally a hardware engineer but the actual hardware work was disappointing compared to the work I’d been doing (I’d never designed from price lists before!). I got sucked into the BIOS effort and then went on to work on early forms of networking (but, again, it was all “do it fast, do it cheap” which ultimately caught up with the company).

Back in my BBS days, I came across an image that was designed to look like marketing copy. It had a picture of several PS/2 pcs, and text which read something along the lines of ‘The IBM PS/2: Yesterday’s technology… today!’.

That one never ceased to elicit a chuckle,

There were a few non compatible systems that ran DOS. I have a Zenith Z100. S100 bus. 8088 and 8085 cpu (for CP/M). Up to 768k RAM 640×225 8 color graphics. I think DOS 3.3 was the last version of DOS for it. There was a port of Windows 1.0 for it.

There was a native Lotus 123 but many DOS programs just worked. I had MS Fortran, Pascal, Multiplan, Turbo Pascal, PC-TeX, Opus BBS. Anything graphical needed a port (and TP and TeX had them)

Hi! Sound’s cool! S100 was quite professional compared to ISA, I think.

Here in former W-Germany we had the c’t-86 computer in mid-80s, using ECB cards.

It was a kit/homebrew project by c’t Magazin, a popular computer magazine of the time.

Schematics, PCB copies and listings were published in several issues, if my memory serves me well.

The computer used an 8086 and had a monitor program, which over the years got PC BIOS compatibility.

In its simplest form, I think, it had a character generator card and programs such as Norton Commander had to be patched to run.

There also were various expansion cards, such as a CGA card

(because of its composite video out; worked with ordinary video monitors so common at the time).

Originally, the magazine had offered a service to alter CP/M-86 or MS-DOS so it would boot on that platform.

To do so, the user had to send in an original (!) floppy disk for modification, perhaps with a proof of purchase even, not sure.

It was very bureaucratic indeed, even by our standards.

But anyway, we in Europe were used to such silly things, I guess.

For example, we used AutoCAD dongles way into the 90s,

when people in North America got rid of them by late 80s already due to user protests.

Anyway, the ct-86 wasn’t exactly intended as an IBM clone.

It rather sort of developed into one over the years, when IBM PC compatibility became important.

In East Germany, they had an Z80 (U880) CP/M computer called the AC-1, Amateur Computer 1.

It was made by radio amateurs and published in Funkamateur magazine.

It was originally intended as a computer for RTTY, which was popular at the time.

Then there also was the (in)famous KC85, too, a home computer. A C64 counterpart, sort of.

That’s what young had worked with, rather. But computers as such were rather rare in E-Germany, that being said.

Office computers running DOS (DCP) were the 8086-based (K1810WM86) Robotron PCs, such as A7150 (CM1910), EC1834 etc.

They’ve used MMS16 bus sytem, based itself on the K1520 bus system (8-Bit).

More information:

https://www-robotron–net-de.translate.goog/pc_s.html?_x_tr_sch=http&_x_tr_sl=de&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=wapp

In USSR of late 80s/early 90s there was the Poisk-1 home computer.

It was a home computer that emulated CGA in software.

Often it was running MS-DOS or a variant called SF-DOS (“Sigma Four” DOS).

http://www.oldcomputermuseum.com/poisk.html

Other home computer style/keyboard style PC/XTs: In Yugoslavia, there was the Lira 512.

In Italy, there was the Prodest PC1 by Olivetti, in W-Germany there was the Schneider Euro PC.

Bulgaria had the Pravetz 16, also. Another solid PC/XT clone.

https://www.pc-freak.net/blog/pravetz/

Then last but not least, there was an Apple2/PC hybrid from Greek called “KAT” by a company named “Gigatronics”.

Very interesting idea, since Apple II was very popular before IBM PC.

The Z100 had a character generator. You could also remap keys. Both could be put into the autoexec file to persist. There was an APL IIRC.

For OSes, the Z100 had CPM-85, CPM-86, Concurrent CPM, UCSD pSystem and I think MP/M available. There was a hard drive expansion card and it worked with the 1st dos version.

There were 2 hardware PC emulators available, but because you could have 768k, someone was able to write a software emulator that mapped the video. ZPC II was the name. Some programs needed patches to run under it, but there was a wide number that did not.

What was a crazy system back in the day was the Xerox 820 which was a standard CP/M machine running at 4MHz IIRC but the optional 80286 add-on board would run CPM/86 simultaneously and you switched between the two with keyboard sequences. I don’t think I ever tried sharing data between them but there was some shared memory. So I could start a compile on Turbo Pascal then switch over to WordStar to write up documentation.

And people wonder why some of use disliked single processing systems like DOS and DOS/Windows when exposed to multi-tasking CP/M and UNIX in the 1980s.

That’s a really impressive system, indeed! 😃

Though I may add that it was possible to multitask on a PC/XT, too.

There were IBM TopView and Quarterdeck DESQView for DOS, for example. Or Borland Sidekick (utility), MP/M 86.

Or special multitasking DOSes: Concurrent DOS, PC-MOS/386 (ran on 8088/286, but limited), Wendin DOS.

Even old Digital Research’s DOS Plus 1.2 could multi-task a little bit, albeit merely CP/M-86 programs.

Once a DOS program was started, the MS-DOS 2.11 emulator “PC MODE” was taking over (PC MODE was like WINE, but for DOS).

That being said, the Xerox had two independent CPUs and did offer true multitasking that way.

It took years into the 90s that PCs with two processors or multiple cores became common.

So if I remember correctly the original IBM PC had a 9 bit memory bus with a socket for a 9th parity bit memory chip that I don’t think was ever utilized. Can anyone confirm/deny this?

Yes, the original IBM PC used a 9-bit DRAM bus to provide parity protection for data content. If a data error was detected, an NMI (non-maskable interrupt) would occur to hang the system. This prevented corrupted data from getting saved to disk. So those extra bits were used.

Clone systems dropped this feature to save costs.

Modern x86 servers still include extra bits to not only detect errors, but to self-correct them.

This is my sense of things: The problem with IBM and their personal computers is that they neither understood their own own creation, nor their customer base.

I was under the impression that, internally, the PC was regarded by many in the organization with derision and disdain. After all, “we’re a mainframe company.” I’ m no IBM historian, but I would guess the closest thing they had to a “personal computer” up to that point might have been something like the Series 1. It’s as though their own leadership regarded the PC project as a toy.

When the PC became successful beyond their wildest dreams, and clone and accessory card makers ate their lunch, they launched the PS2 series. I recall those machines being very nice… typical high-quality IBM.

The problem is those machines didn’t really do anything a contemporary clone couldn’t do for a lot less money, and accessory cards were so encumbered with royalties for the license to Micro Channel that those cards may as well not exist.

Example: I worked at a business that specified IBM for their office computers, and I had direct experience working with various models in the PS2 family. I also remember buying a Micro Channel Hayse modem card for one of those machines that cost 8 times as much the same Hayse model engineered for the ISA bus.

In short, IBM’s first mistake was apathy, its second, greed. In an alternate universe/timeline, where they navigated successfully between those two rocks, IBM would probably be king to this day.

Their third mistake? Repetition.

One of my buddies dads worked at IBM, when we were kids he had a mighty PS/2-80 tower which was a huge beast with a very sturdy handle on top to lug it about. It had some weird not-CMOS memory for storing BIOS settings which invariably went wrong and the machine had to be reset / re-configured every so often. The MCA cards were a rare commodity and even the chips used on some of the boards were very different, I remember aluminium sugar cube shaped lumps on one board in there.

Our school had the lower end PS/2 386 desktops.

For all their flaws the mechanical engineering on those units was insanely high end, I never worked out what the cases were made of, they felt like cast metal of some sort… and those massive power switches were so satisfying!

Quite a number of inaccuracies. “You probably couldn’t plug a 16-bit card into an 8-bit slot, though, unless it was made to work that way” – about all 16-bit cards also worked in 8-bit slots, especially in the earlier days of the AT. “The original PC used some extra logic in the keyboard controller to handle the gate.” – no, the original PC didn’t have the “gate”, as it didn’t have the 21st address line.

Um, it depends, I would say. 😅

Many 16-Bit ISA cards have a fall-back for 8-Bit slots, that’s true.

Things such as VGA cards, for example.

Because I think VGA was meant for 16-Bit PCs originally (AT ir PS/2)

and thus the same 16-Bit VGA chips were usually put on budget cards with 256KB video RAM/8-Bit bus, too.

It made more sense than developing different versions especially for 8-Bit bus, I guess.

It also gave XT users the option to have more expensive, “full” versions of the VGA cards with their vast 512KB or 1MB of video RAM.

Or with extra crystals installed for 800×600 and 1024×768 resolution.

Then you had the NE2000 standard of network cards.

It became so widespread that the 8-Bit version, NE1000, was withdrawn quickly.

After all, the Novell NE2000 could operate in 8-Bit slots, too.

Most NE2000 clones kept that backwards compatibility,

except some NICs such as some version of the very popular Etherlink III.

The Com 3c509 doesn’t work correctly in an 8-Bit slot.

It needs the 3Com 3c509b for that (B version).

The serial/parallel, game and floppy controllers on ISA multi-i/o cards are natively 8-Bit devices.

EMS memory boards are often using 8-Bit i/o, too, even those with a full 16-Bit connector (thinking of AST Rampage etc).

But then you have the IDE interface which uses full 16-Bit bus,

for example (IDE HDDs used to be called AT Bus HDDs btw; and yes there was an 8-Bit XTIDE once).

On the 16-Bit extension of the PC bus there are additional IRQ and DMA lines, 0 wait state line, additional address line.

8-Bit cards can only address 1 MB, 16-Bit cards can address up to 16 MB.

So yeah, while in most cases all the important stuff is on the 8-Bit part of the ISA bus, there are exceptions too. 🙂

Another problem that comes to mind is the use of 80286 (80186) or 80386 instructions on some ROM chips installed on 16-Bit ISA cards.

Because, the 8088 used on most XT motherboards has an outdated instruction set that doesn’t them (new ones use 8086-2).

So unless a NEC V20 or a CPU accelerator card is installed, that code doesn’t run when loaded at boot-up.

I’m thinking of option ROMs for VGA cards, SCSI controllers, boot ROMs for Novell networks or the loader of DiskOnChip-2000 devices.

Devices that use optimized code with later instructions for performance reasons, in short.

The latter are very old SSD-like chips that use a boot loader.

It has to be re-flashed for 8086/8088 use, as far as I remember.

That being said, it’s not really a bus issue but more of a processor issue.

Many XTs had a plain old 8088, unless upgraded or of more modern nature (Turbo XTs etc).

If anyone has the opportunity to watch the series “Halt and Catch Fire”, it’s a great story of the BIOS shenanigans in the clone world back then.

I’m posting a bit late, but that series, or at least the first season, is often promoted and reviewed as a fictionalized story of Compaq. I added much of the following info to the Wikipedia page on “Corona Data Systems”, so I’ll just quote “Like Cardiff Electric’s fictional pivot to become a PC manufacturer, Corona Data System’s actual history included founding by two individuals: a computer systems expert (Harp) and a marketing/sales executive (Kramarz), with a design of a portable IBM PC-compatible. While Cardiff Electric and Compaq succeeded in fighting IBM’s accusations of copyright infringement with clean room designed BIOS, Corona did not. Also like Cardiff, Corona Data Systems in 1985 was sold a majority share to a conglomerate” and the Daewoo Group gutted CDS, the company as a tax write off. So, the show’s very fictionalized depiction of reverse engineering of BIOS, and the Texas location, echoed Compaq, but the rest is right from the history of CDS(later called Cordata).

The beginning of the article implied that IBM developed the PC to “get rid of some surplus keyboards”. LOL. Actually IBM thought that there was a viable market among hobbyists, who would then influence the companies they worked for to try out the PC for business users. It was a kind of “backdoor” approach to marketing to businesses. It worked. After a short time the backdoor approach wasn’t needed. It was selling to businesses on its own via clever advertising.

Halt and catch fire, has an interesting dramatic take on that period.

Correction/Clarification: IBM sold it’s “server” division to Lenovo in 2014. But that was just their ‘small’ x86 server division.

IBM still makes mainframes and supercomputers which are servers.

In fact, since IBM is primarily a research corporation their servers are way ahead of the x86 stuff because they don’t have to wait for a standards organization before throwing any new tech into the wild.

And their customers (like banks) expect way more support, so they can harge big $$$ for it.

A modern PowerPC mainframe is an exotic beast compared to such ‘mundanity’ as an EPYC or even a (insert whatever NVidia is selling to ruin everything with ‘AI’ this quarter).

You can do crazy stuff like plu in a drawer of flash and let one of the programmable logic cores act as a controller.

Or how about connecting multiple CPUs together in a cluster? No not like that, I mean hot swappable interconnects directly between the cores so they can pull cache or access memory with their own controller.

Speaking of memory, need to hot swap your memory controller? Go for it.

Need something silly? Well you are already paying multiple millions of dollars and even more millions for onsite IBM support, just have them make you something custom.

Too bad they are one of the biggest ‘compute’ enablers for the ‘evil’ surveillance states…

Super cool gear, used for evil.

The primary motivator for opening the IBM specifications was because of anti trust. This video goes into more detail about this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2VNivXjrU3A