Writing good, performant code depends strongly on an understanding of the underlying hardware. This is especially the case in scenarios like those involving embarrassingly parallel processing, which at first glance ought to be a cakewalk. With multiple threads doing their own thing without having to nag the other threads about anything it seems highly doubtful that even a novice could screw this up. Yet as [Keifer] details in a recent video on so-called false sharing, this is actually very easy, for a variety of reasons.

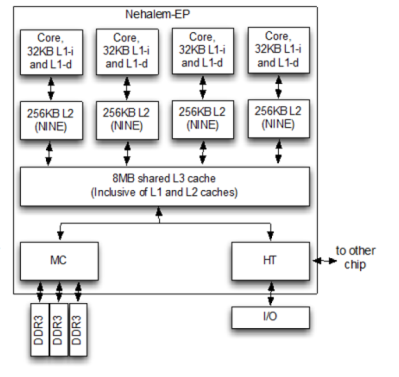

With a multi-core and/or multi-processor system each core has its own local cache that contains a reflection of the current values in system RAM. If any core modifies its cached data, this automatically invalidates the other cache lines, resulting in a cache miss for those cores and forcing a refresh from system RAM. This is the case even if the accessed data isn’t one that another core was going to use, with an obvious impact on performance. As cache lines are a contiguous block of data with a size and source alignment of 64 bytes on x86, it’s easy enough to get some kind of overlap here.

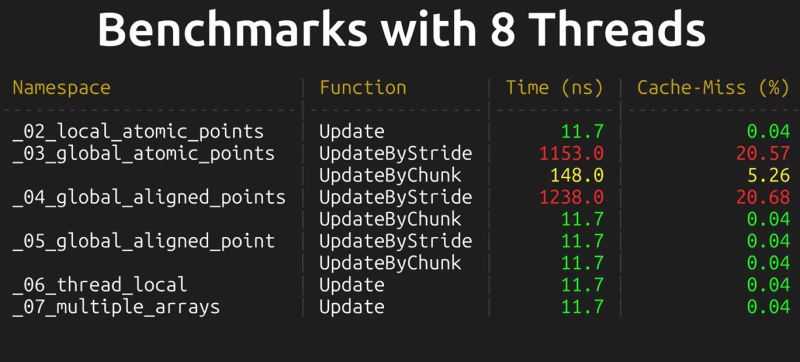

The worst case scenario as detailed and demonstrated using the Google Benchmark sample projects, involves a shared global data structure, with a recorded hundred times reduction in performance. Also noticeable is the impact on scaling performance, with the cache misses becoming more severe with more threads running.

A less obvious cause of performance loss here is due to memory alignment and how data fits in the cache lines. Making sure that your data is aligned in e.g. data structures can prevent more unwanted cache invalidation events. With most applications being multi-threaded these days, it’s a good thing to not only know how to diagnose false sharing issues, but also how to prevent them.

A long way from needing ChatGPT to set up a list of books! Impressive.

Shared memory doesn’t scale because of the cache invalidation traffic. Large scale systems use message passing in one form or another.

The sooner that is made explicit in programming languages, the better.

Shared nothing is just too slow to be practical, though. There are some clever approaches to shared data, such as partitioning. Make sure certain threads prefer to touch some parts of the dataset (or other resource) and others other parts, so that they do not (usually) step on each other’s toes.

Linux scheduler for instance tries to keep threads on the same NUMA node (basically CPU socket + RAM on multi-socket servers) as the NIC (network interface card) the packets arrive through, so that there is no bulk intra-CPU-socket traffic.

But it still allows coherent concurrent access to all of memory (with associated latency costs), which drastically simplifies the software architecture as opposed to full clustering required to reclaim coherence with shared-nothing.

Are the US national labs are running tens of thousands of copies of Doom on their systems? Nothing is ‘shared’ in message passing programming, but it is extraordinarily practical for oh so many problems. If you want performance, you learn not to share–real and false, hardware and software.

The high performance computing (HPC) mob are extremely sensitive to performance and scalability. They have a long and glorious history of pushing computing to the limits, finding what is possible – and then inventing new mechanisms to further improve performance.

They use message passing in various forms.

I am pretty sure this exact scenario has been addressed by certain Seymour Cray.