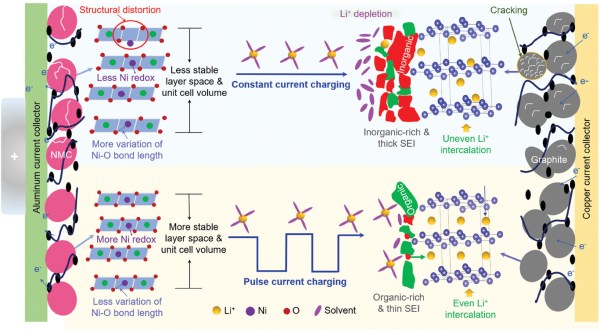

For as much capacity lithium-ion batteries have, their useful lifespan is generally measured in the hundreds of cycles. This degradation is caused by the electrodes themselves degrading, including the graphite anode in certain battery configurations fracturing. For a few years it’s been known that pulsed current (PC) charging can prevent much of this damage compared to constant current (CC) charging. The mechanism behind this was the subject of a recent research article by [Jia Guo] and colleagues as published in Advanced Energy Materials.

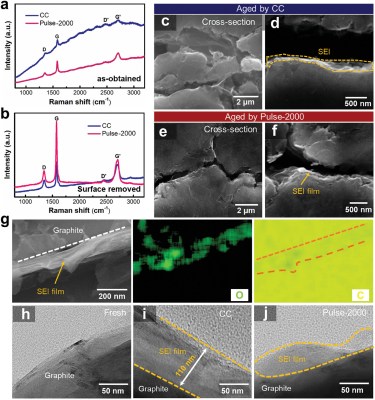

The authors examined the damage to the electrodes after multiple CC and PC cycles using Raman and X-ray absorption spectroscopy along with lifecycle measurements for CC and PC charging at 100 Hz (Pulse-100) and 2 kHz (Pulse-2000). Matching the results from the lifecycle measurements, the electrodes in the Pulse-2000 sample were in a much better state, indicating that the mechanical stress from pulse current charging is far less than that from constant current charging. A higher frequency with the PC shows increased improvements, though as noted by the authors, it’s not known yet at which frequencies diminishing returns will be observed.

The use of PC vs CC is not a new thing, with the state-of-the-art in electric vehicle battery charging technology being covered in a 2020 review article by [Xinrong Huang] and colleagues as published in Energies. A big question with the many different EV PC charging modes is what the optimum charging method is to maximize the useful lifespan of the battery pack. This also applies to lithium-metal batteries, with a 2017 research article by [Zi Li] and colleagues in Science Advances providing a molecular basis for how PC charging suppresses the formation of dendrites .

What this demonstrates quite well is that the battery chemistry itself is an important part, but the way that the cells are charged and discharged can be just as influential, with the 2 kHz PC charging in the research by [Jia Guo] and colleagues demonstrating a doubling of its cycle life over CC charging. Considering the amount of Li-ion batteries being installed in everything from smartphones and toys to cars, having these last double as long would be very beneficial.

Thanks to [Thomas Yoon] for the tip.