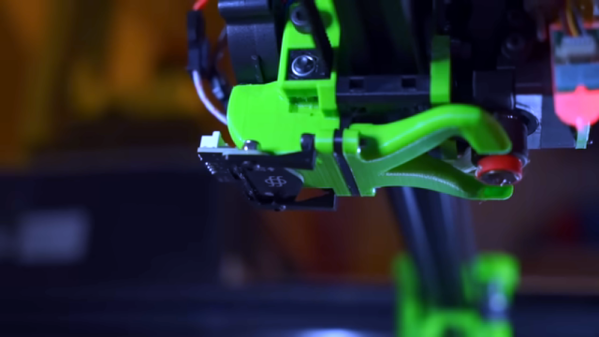

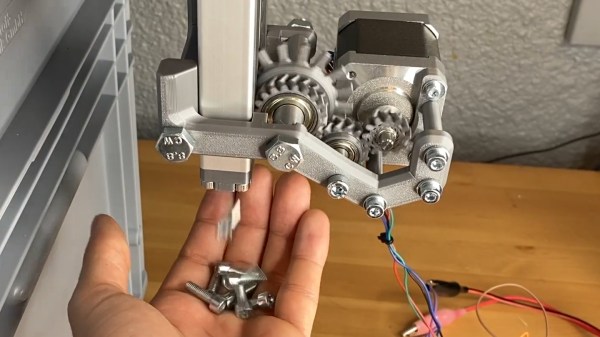

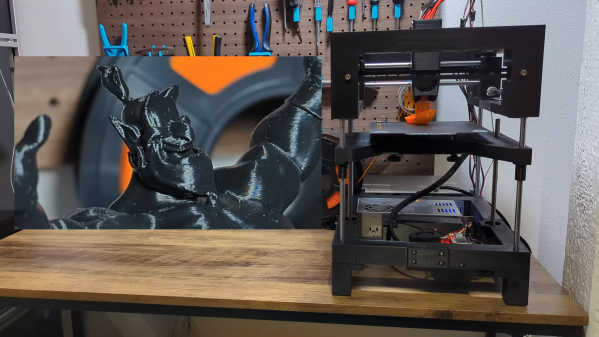

The bane of 3D printing is what people commonly call bed leveling. The name is a bit of a misnomer since you aren’t actually getting the bed level but making the bed and the print head parallel. Many modern printers probe the bed at different points using their own nozzle, a contact probe, or a non-contact probe and develop a model of where the bed is at various points. It then moves the head up and down to maintain a constant distance between the head and the bed, so you don’t have to fix any irregularities. [YGK3D] shows off the Beacon surface scanner, which is technically a non-contact probe, to do this, but it is very different from the normal inductive or capacitive probes, as you can see in the video below. Unfortunately, we didn’t get to see it print because [YGK3D] mounted it too low to get the nozzle down on the bed. However, it did scan the bed, and you can learn a lot about how the device works in the video. If you want to see one actually printing, watch the second, very purple video from [Dre Duvenage].

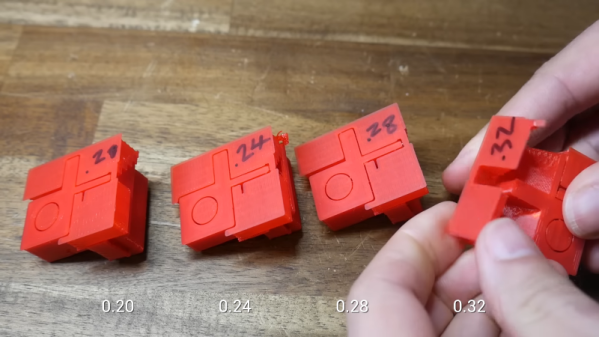

Generally, the issues with probes are making them repeatable, able to sense the bed, and the speed of probing all the points on the bed. If your bed is relatively flat, you might get away with probing only 3 points so you can understand how the bed is tilted. That won’t help you if your bed has bumps and valleys or even just twists in it. So most people will probe a grid of points.