The Hackaday Prize is a celebration of the greatest hardware put together by the greatest hackers on the planet. If you go over the entries, you’ll find user interfaces for everything. Need a wheelchair controlled by eye gaze? That won last year. A foot controlled mouse? Done. Need a device to talk to the Internet while you’re in a lucid dream? We’ve seen that.

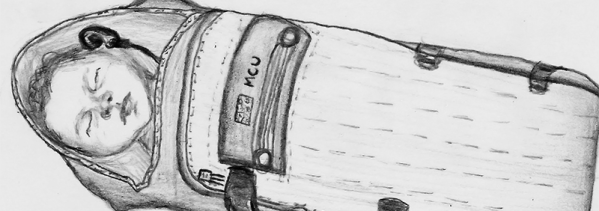

We’ve seen a lot of really cool, really strange stuff in the Hackaday Prize. We haven’t seen anything like Pallette, a finalist for the Assistive Technologies portion of this year’s prize. It’s a tongue-computer interface. You put Pallette in your mouth, like a retainer, and you can control a computer. Telekinesis with a tongue.

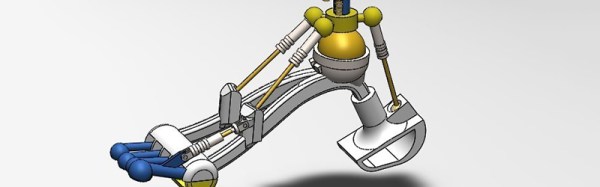

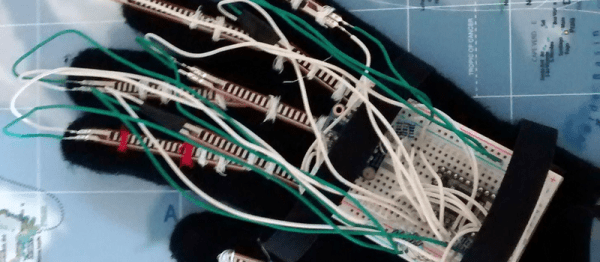

At its most basic level, Pallette is a Bluetooth mouse, hidden away behind the lower jaw. Infrared sensors triangulate the position of the tongue, and a microphone detects the tongue tapping on Pallette. Everything you can do with a mouse can be done with Pallette.

At first glance, Pallette seems to be just a little bit absurd. This idea changes when you see the video the Pallette team produced for the Hackaday Prize finals. Some people can’t use their arms, and for this, Pallette is a godsend. With this, anyone can use a computer, control a Sphero, or fly a drone. It’s a completely novel device that can be used for anything, and an excellent example of what we’re looking for in the Hackaday Prize.

Continue reading “Hackaday Prize Entry: Tongue Computer Interface”