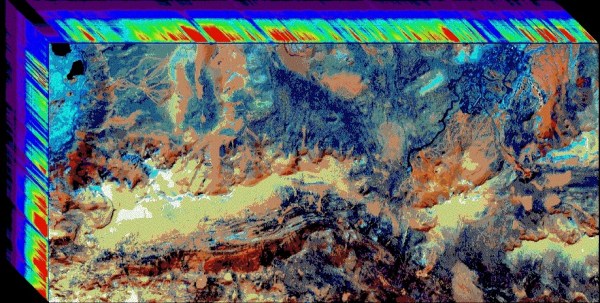

Hyperspectral cameras aren’t commonplace items; they capture spectral data for each of their pixels. While commercial hyperspectral cameras often start in the tens of thousands of dollars, [anfractuosity] decided to make his own with the Waverider.

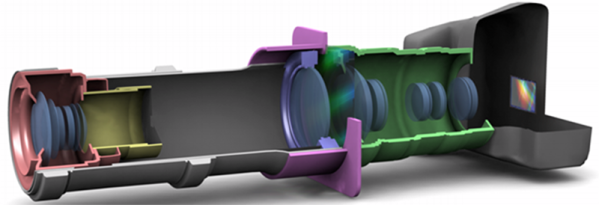

To capture spectral data from every pixel location in the camera, [anfractuosity] first needed a way to collect that data — for that, he used an AFBR-S20M2WV, a miniature USB spectrometer he picked up second-hand. This sensor allows for the collection of data from 225 nm all the way up to 1000 nm. Of course, the sensor can only do that for one single input, so to turn it into a camera, [anfractuosity] added a stepper-driven x-y stage controlled by a Raspberry Pi Pico and some TMC2130 stepper drivers.

Continue reading “Waverider: Scanning Spectra One Pixel At A Time”