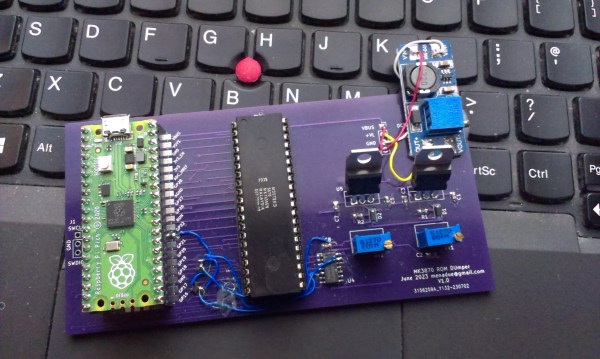

If you buy any kind of electronic gadget today, chances are it’s powered by a microcontroller with a program stored in its internal flash ROM. That program’s code is often jealously guarded by the manufacturer, who will try their best to make sure you can’t just read back the chip’s contents by using lock bits or some sort of encryption. Things were more laid back in the 1970s and ’80s, when code was stored unencrypted in standard EPROM chips, or, for high-volume applications, in mask ROMs integrated in microcontrollers. Reading back the code of such micros was still very difficult because chips simply didn’t have a way of dumping their contents. [Andrew Menadue] ran into this issue when trying to repair an old HP calculator printer, and had to apply a clever hack to dump the contents of its Mostek MK3870 chip.

The main trick [Andrew] used was one discovered by [Sean Riddle] and explained on his website. It makes use of the fact that the MK3870 has a TEST pin that can be used to disable the mask ROM and load alternative program code directly into the micro’s processing core. By setting up a LOAD instruction pointing at a ROM location and briefly disabling test mode while that instruction is executed, the ROM’s contents can be read out by the externally loaded program.

Simple as this hack may seem, actually implementing it was tricky enough because of the strict timing requirements between signals on the clock pins, the data bus, and the TEST pin. [Andrew] got it to work on his Raspberry Pi Pico setup most of the time, but somehow the micro still returned a plainly wrong value every few hundred bytes. Not willing to spend too much time debugging this issue, [Andrew] applied a rather crude hack to his code: instead of reading each byte once, it runs the read cycle 200 times, and only returns a result when all 200 runs return the same value. Dumping the entire 4 kB of ROM now takes several minutes, but this isn’t much of an issue since [Andrew] only has one chip to read out.

If you do have a bucketload of MK3870 chips that you need to dump, you might want to try and optimize the code on [Andrew]’s GitHub page. It’s a lucky coincidence that the ‘3870 has the exploitable TEST feature; often, the only way to get inside mask ROM code is by decapping the chip and optically reading the bits one by one. Mask ROMs are great for very long term data storage, however.