We were talking about [Maya Posch]’s rant on smartphones, “The Curse of the Everything Device”. Maya’s main point is that because the smartphone, or computer, can do everything, it’s hard for a person to focus down and do one thing without getting distracted, checking their whatever feed, or getting an important push notification about the Oscars. She was suggesting tying your hands to the mast by using a device that can only accommodate the one function, like a dedicated writing tool or word processor.

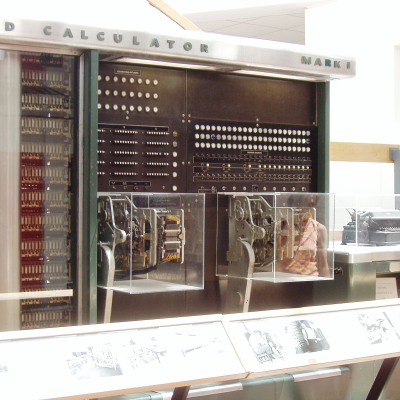

[Kristina Panos] compared the all-singing, all-dancing black rectangle to an everything-device of old: the all-in-one stereo receiver with built-in tape player, record player, and not just FM, but also AM radio receiver. The point being, the hi-fi device also does a whole lot of things but isn’t similarly cursed. The tape player never interrupts your listening to the AM radio station. When the record is over, it doesn’t swap over to FM. Your agency is required.

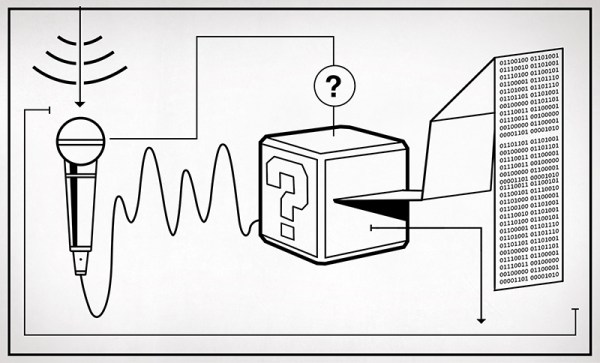

Similarly, it’s probably not intrinsically problematic that the smartphone has a camera, a web browser, text messages, and heck even a telephone built in. It’s how they interact with each other and the user, each vying for user attention, and interrupting with popups and alarms. It’s maybe a simple matter of software! (Says the hardware guy.)

Where would a distraction-free, but fully featured, phone begin? With the operating system? It would be perverse to limit you to one app at a time, or to make switching between them more cumbersome. How about turning off notifications, and relying on changing context only when you think about it? Maybe that’s a middle ground. How do you cope with the endless distractions offered to you by your smartphone? By your main computer?