If you are in the habit of seeking out abandoned railways, you may have stood in the shadow of more than one Victorian iron bridge. Massive in construction, these structures have proved to be extremely robust, with many of them still in excellent condition even after years of neglect.

When you examine them closely, an immediate difference emerges between them and any modern counterparts, unlike almost all similar metalwork created today they contain no welded joints. Arc welders like reliable electrical supplies were many decades away when they were constructed, so instead they are held together with hundreds of massive rivets. They would have been prefabricated in sections and transported to the site, where they would have been assembled by a riveting gang with a portable forge.

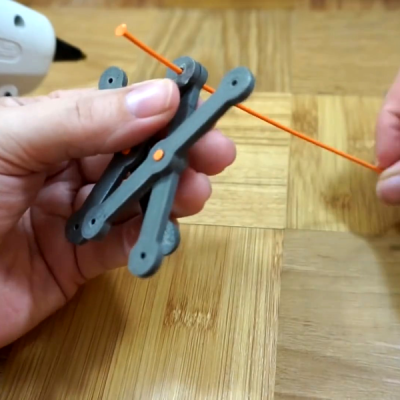

So for an audience in 2018, what is a rivet? If you’ve immediately thought of a pop rivet then it shares the function of joining two sheets of material by pulling them tightly together, but differs completely in its construction. These rivets start life as pieces of steel bar formed into pins with one end formed into a mushroom-style dome, probably in a hot drop-forging process.

A rivet is heated to red-hot, then placed through pre-aligned holes in the sheets to be joined, and its straight end is hammered to a mushroom shape to match the domed end. The rivet then cools down and contracts, putting it under tension and drawing the two sheets together very tightly. Tightly enough in fact that it can form a seal against water or high-pressure steam, as shown by iron rivets being used in the construction of ships, or high-pressure boilers. How is this possible? Let’s take a look!