The good part about older game consoles like the Super Nintendo is that they have rather rudimentary region locks, but unfortunately this also gives some people the idea that installing something like the SuperCIC mod chip to make a SNES region-free is easy. The patient that arrived on [Skawo]’s surgery table was one such victim, with the patient requiring immediate surgery to remove the botched installation before assessing the damage.

Here the good news was that the patient features the revision B CPU, making it a good console to rescue. The bad news was that the pads of the old CIC chip had been ripped up, there was a solder bridge on S-PPU1 between two pins and both the installed wiring and soldering were atrocious, requiring plenty of touch-ups.

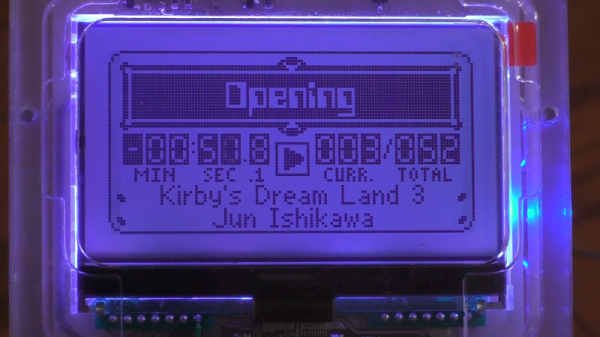

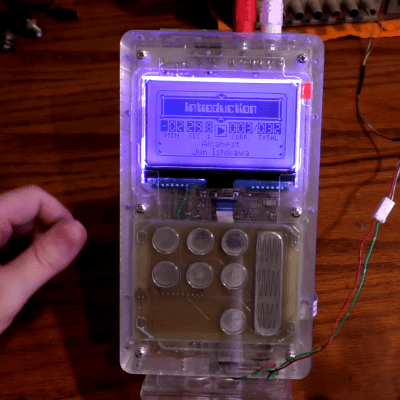

With the CIC pads already a loss, finishing the SuperCIC mod seemed like a good plan, also since this would make for a nice region-free console. This mod involves a PIC16F630 with special firmware that works with the corresponding CIC IC in each cartridge, while also switching between 50/60 Hz mode to fit the cartridge’s region. After an initial test with PAL and NTSC cartridges everything seemed all right. Then [Skawo] ran the SuperNES Burn-In test from its cartridge, which gave dire news.

Continue reading “Fixing The Damage Of A Botched SNES SuperCIC Mod”