[Laena] and her colleagues at the La Trobe Institute for Molecular Science in Melbourne, Australia used a Raspberry Pi to make a low-cost electrochemiluminescence (ECL) detector to measure inflammation markers, which could be used to detect cardiovascular disease or sepsis early enough to give doctors a better chance at saving a patient’s life.

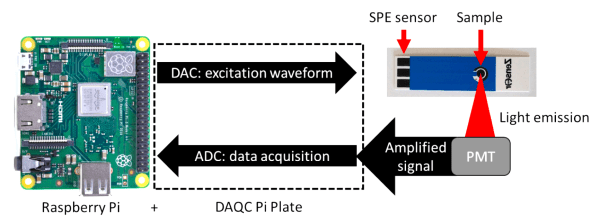

ECL reactions emit light as a result of an electrically-activated chemical reaction, making them very useful for detecting biochemical markers in blood, saliva, or other biological samples. ECL setups are fundamentally fairly straightforward. The device includes a voltage reference generator to initiate the chemical reaction and a photomultiplier tube (PMT) to measure the emitted light. The PMT outputs a current which is then converted to a voltage using a transimpedance amplifier (TIA). That signal is then sampled by the DAQCplate expansion board and the live output can be viewed in ppLOGGER in real-time.

Using the RPi allowed the team to do some necessary, but pretty simple signal processing, like converting the TIA voltage back to a photocurrent and integrating the current to obtain the ECL intensities. They mention the added signal processing potential of the RPi was a huge advantage of their setup over similar devices, however, simple integration can be done pretty easily on most any microcontroller. Naturally, they compared their device to a standard ECL setup and found that the results were fairly comparable between the two instruments. Their custom device showed a slightly lower limit of detection than the standard setup.

Their device costs roughly $1756 USD in non-bulk quantities with the PMT being the majority of the cost ($1500). Even at almost $2000, their device provides more than $8000 in savings compared to ECL instruments on the market. Though cost is much more than just the bill of materials, we like seeing the community making efforts to democratize science, and [Laena] and her colleagues did just that. I wonder if they can help us figure out the venus fly trap while they’re at it?