A lot of people can bake a cake. Sort of. Most of us can bake a cake if we have a cake mix. Making a cake from scratch is a different proposition. Sure, you know it is possible, but in real life, most of us just get a box of cake mix. The Raspberry Pi isn’t a cake (or even a pie), but you could make the same observation about it. You know the Raspberry Pi is just an ARM computer, you could program it without running an available operating system, but realistically you won’t. This is what makes it fun to watch those that are taking on this challenge.

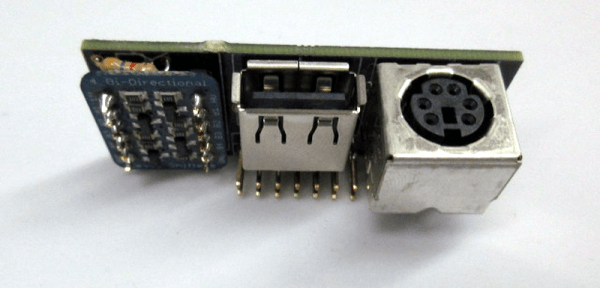

[Deater] is writing his own Pi operating system and he faced a daunting problem: keyboard input. Usually, you plug a USB keyboard into the Pi (or a hub connected to the Pi). But this only works because of the Linux USB stack and drivers exist. That’s a lot of code to get working just to get simple keyboard input working for testing and debugging. That’s why [Deater] created a PS/2 keyboard interface for the Pi.

Even if you aren’t writing your own OS, you might find it useful to use a PS/2 keyboard to free up a USB port, or maybe you want to connect that beautiful Model-M keyboard without a USB adapter. The PS/2 keyboard uses a relatively simple clock and data protocol that is well-understood. The only real issue is converting the 5V PS/2 signals to 3.3V for the Pi (and vice versa, of course).