World War II can be thought of as the first electronic war. Radio technology was firmly established commercially by the late 1930s and poised to make huge contributions to the prosecution of the war on all sides. Radio was rapidly adopted into the battlefield, which led to advancements in miniaturization and ruggedization of previously bulky and fragile vacuum tube gear. Radios were soon being used for everything from coordinating battlefield units to detonating anti-aircraft artillery shells.

But it was not just the battlefields of WWII that benefitted from radio technology. From apartments in Berlin to farmhouses in France, covert agents toiled away over sophisticated transceivers, keying in coded messages and listening for instructions. Spy radios were key clandestine assets, both during the war and later during the Cold War.

The Limping Lady

Virginia Hall had all the makings of a diplomat. Impeccably educated, fluent in multiple languages, and worldly from her years spent abroad from her native Baltimore, Virginia’s dream of a life in the foreign service was shattered when a hunting accident led to the amputation of her left leg. Attitudes toward disabilities were different in the 1930s, and even fitted with a prosthetic leg (which she named “Cuthbert”) Virginia was deemed unfit for the life of a diplomat.

The outbreak of WWII changed that attitude. Virginia, by then living in France, was well-placed to act as a forward agent for the Allies. Volunteering first for the British Special Operations Executive (SOE), Virginia worked agents, ran safehouses, and reported intelligence from Vichy France. Later, she volunteered with the US Office of Strategic Services (OSS), forerunner to the CIA. Her efforts earned her a place on the Gestapo’s “Most Wanted” list as “The Limping Lady”. She and Cuthbert continued to work against the Nazis right up through the Normandy invasion and liberation and earned a Distinguished Service Cross for her efforts – a rare honor for a civilian, and rarer still for a woman.

Behind Enemy Lines

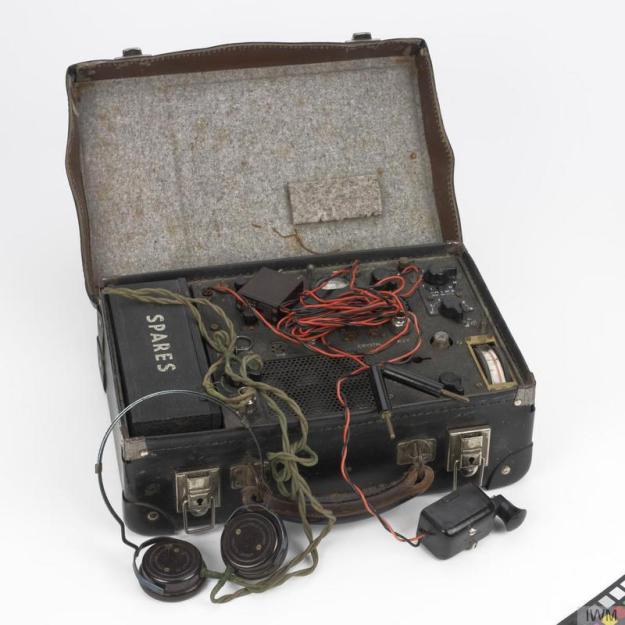

While Virgina was adept in all aspects of tradecraft, one of the most powerful tools at her disposal was the suitcase radio, a catch-all term used to describe any transceiver small enough to be transported into the field and operated covertly. A suitcase was often used to house the radio as it would be less likely to arouse suspicion if the spy’s lair was discovered. The suitcase was also a great form factor for a portable transceiver – just the right size for the miniaturized radios of the day, good operational ergonomics, and perfect for quick setup and teardown. You can even imagine a spy minimally obfuscating the suitcase’s real purpose with a thin layer of folded clothing packed over the radio.

Great care was given to ensure that the field agent would have every chance of using the radio successfully and that it would operate as long as possible under adverse conditions. With a power budget often limited to five watts or so, these radios were strictly QRP affairs. Almost every suitcase rig operated on the high-frequency bands between 3 MHz and 30 MHz, to take advantage of ionospheric skip and other forms of propagation. An antenna optimized for these bands would likely be a calling card to the enemy, especially in an urban setting, so controls were provided to tune almost any length of wire into a decent antenna.

While some radios were capable of AM voice transmission, continuous wave (CW) modulation and Morse code was used almost exclusively for their ability to punch a signal through any natural (QRN) or man-made (QRM) interference, the latter often being intentional jamming by the enemy. And to make sure the radio kept running, a full set of spares – fuses, tubes, crystals – was provided. Most radios even had a full schematic for troubleshooting. Operators were also meticulously trained:

While the suitcase ruse was perfect for urban and even rural operations, something a little sturdier was needed for true field operations. Resistance forces often found themselves deep in enemy territory and working outdoors in all weather conditions, so a waterproof radio was needed. The British B2 radio was a good example of this; one variant was housed in two metal housings with padding for the delicate electronics. The waterproof containers were designed to be dropped to covert agents on a parachute and lugged around like a backpack.

Bugs In Their Shoes

The end of WWII was by no means the end of electronic intelligence. Indeed, the advances in electronics spurred by the war gave the spies even more toys to prosecute the next phase of the twentieth century’s seemingly unending wars – the Cold War.

Foreign service officers have always enjoyed diplomatic immunity, which today in places like New York City also apparently extends to parking ticket immunity. But it also makes any diplomatic mission a thinly disguised nest of spies in the host country. To take advantage of this, countries go to great lengths to gather data. Sometimes it’s as simple as reading the local newspaper or watching activities at the docks or airport, and reporting information back to the home country in the inviolable diplomatic pouch. But some information is harder to get and requires a little electronic assistance. That’s when the bugs come into play.

Some Cold War bugs were hugely successful, like Theremin’s “Great Seal Bug” placed by Russian agents in the US Ambassador’s residence in the late 1940s. It operated for nearly seven years before being discovered; the secret to its longevity was its passive operation, depending upon a resonant cavity that could transmit voice when illuminated by high-power radio waves. In hindsight, a group of Soviet scouts presenting an ambassador with an enormous carved wooden plaque probably should have seemed suspicious.

Perhaps more subtle was the Romanian Securitate’s attempts to bug diplomats in the 1960s and 1970s. Fashion not being a strong suit of Iron Curtain countries back in the day, Western diplomats in Romania preferred to order their attire from the fashionable shops of London and New York. With operatives in the Romanian post office, it was easy for the Securitate to intercept packages destined for consular personnel. Men’s shoes were whisked away to the Securitate’s technical division, where the heels were removed so that a tiny transmitter could be installed. The shoe was reassembled, sent on to the diplomat, and it would transmit for several days before the batteries died. One imagines that the audio quality must have been poor; pity the poor Romanian signals analyst listening to hours of shoes clopping down hallways. Such bugs were used up until they were discovered during routine sweeps that revealed the presence of radio signals that disappeared when diplomats were out of the room.

I’ve always maintained that pretty much anything that you can imagine is possible with electronics; as long as it doesn’t violate the laws of physics, whatever you can imagine can probably be built. Few things spur the collective imagination and spirit of invention like war, and nothing focuses effort and resources better. It’s a pity we put so much effort into fighting each other, but you’ve got to admire the ingenuity it takes to create devices like these, and the bravery of the men and women who take them into harm’s way.

Awesome write-up and links! Thank you!

With that setup, I was really expecting to read that Cuthbert had been converted into a radio.

Would probably be the earliest contender for “cyborg” if that was the case. Damn heavy leg though.

Yankee Hotel Foxtrot…. Numbers stations. Wilco.

Loved it! Great article!

No hacks here, move on…

Seriously guys WTF, fascinating stuff but those radios were the best products an entire nation could produce, they were not hacks nor were the users hackers. Nobody would question Hall’s courage but she didn’t even make her own leg.

This is a classic example of a person getting famous because they are well connected rather than because they were above average when compared to everyone else doing the same job.

Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler was a real hacker, Hall is not even in the same league when it comes to technical prowess.

These radios were professionally designed and manufactured … while many more were designed and built in the field, including receivers built from scratch in the PoW camps, and h.idden successfully in ingenious ways.

Exactly, some of the gear that POW and resistance fighters actually hacked together is amazing.

e.g. http://www.zerobeat.net/qrp/powradio.html

These old spy radios, and field radios, are now a niche for some amateur radio operators to DIY build, bonus points for keeping all parts period.

“This is a classic example of a person getting famous because they are well connected rather than because they were above average when compared to everyone else doing the same job.”

Everyone doing that job was at risk of torture and death, and was deserving of respect. Without having served in that capacity, Hall would have remained as unknown to history as any other well-to-do woman of her era.

Recognizing one person doesn’t diminish the jobs the others did, it does not exclude others. Instead, having the story of a person of some external stature helps bring attention to all of them.

Like I said, no hacks here, move on…

Great article, ignore the shitposters. Also the Crypto museum has some fascinating stuff on their website well worth a browse.

You are the sort of fascist that these radios were used against, haven’t heard of the concept of freedom of expression?

You are one of the shitposters Dan.

What is this, a meeting of the Nazi party or something?

You’re using your freedom of speech quite well…

We’re just using our freedom of expression to highlight your stupidity.

I appreciate irony, especially when it is unintended.

u dumb trol

I could never be as dumb as you, you can’t even tell the difference between race and politics.

Dan really knows how to troll. He is one of the best.

Good art

Awesome, right? I binge-watched “Archer” when I saw Joe’s art.

What about the WII Paraset spy radio ? Thousands were made.

http://www.sm7ucz.se/Paraset/Paraset_e.htm

Romania’s State Security (or “Securitate” if you want to keep the romanian name) also used the national telephony network to listen into people’s houses. At that time there were disk telephones, not touch-pad based, and dial was done through pulses to a “penta-conta” (five-contacts)-based switch board in the telephone station. If anyone became suspicious, the national phone company just sent some operator to simulate a malfunction to the telephone line, then he installed a resistor and a capacitor inside the phone. The phone boards had some jumpers just for that. So while the phone receiver was siting on the phone, there was enough power to the big microphone to send some signals through the capacitor back to the phone line. Listening was performed in a special room at the phone company, where not even the lady in charge with cleaning was not allowed to enter.

Interesting, but a little more research would have made the article more relevant to the core HaD reader.

The technology of the historic spy radios appeals to many radio amateurs. For example, the Paraset. This is a well-known version of the WW II suitcase HF spy radio which has proven a popular target for replication by modern hams. http://members.shaw.ca/ve7sl/paraset.html

More recently, I found out about the “adapter set” – a ‘parasitic’ spy radio that relied on common household receivers for power and tubes. Basically, the spy would unplug one of the domestic receiver’s output tubes, plug in the adaptor set, then plug the tube into the adapter. The adaptor set itself could be quite small, and easy to hide and transport. http://theradioboard.com/rb/viewtopic.php?f=8&t=7090

Both these radios are useable by hams today, so there remains considerable interest in replicating and using them.

grrr. HaD comment system. please delete this v1 post. It didn’t show up, no moderation warning, so I double-posted.

Interesting, but a little more research would have made the article more relevant to the core HaD reader.

The technology of the historic spy radios appeals to many radio amateurs. For example, the Paraset (already mentioned). Another link: http://members.shaw.ca/ve7sl/paraset.html

More recently, I found out about the “adapter set” – a ‘parasitic’ spy radio that relied on common household receivers for power and tubes. Basically, the spy would unplug one of the domestic receiver’s output tubes, plug in the adaptor set, then plug the tube into the adapter. The adaptor set itself could be quite small, and easy to hide and transport. http://theradioboard.com/rb/viewtopic.php?f=8&t=7090

Both these radios are useable by hams today, so there remains considerable interest in replicating and using them.

This clandestine minimalist “Mind-Set” lives on today! But it is not related to the Government – much the opposite. Just dig deep into the topic of “Prepper Radio”…

What about people in Nazi Germany who hacked their Volksempfängers (People’ Radios) to receive shortwave, an act which if found out could result in execution! Now that is hard core hacking!

Thanks for the tip.

Excellent article Dan.

Would you mind if I put your article in our ham radio club newsletter? You’d get the credit of course.

so awaresome. thank you