Ever since I first learned about radiosondes as a kid, I’ve been fascinated by them. To my young mind, the idea that weather bureaus around the world would routinely loft instrument-laden packages high into the atmosphere to measure temperature, pressure, and winds aloft seemed extravagant. And the idea that this telemetry package, having traveled halfway or more to space, could crash land in a field near my house so that I could recover it and take it apart, was an intoxicating thought.

I’ve spent a lot of time in the woods over the intervening years, but I’ve never seen a radiosonde in the wild. The closest I ever came was finding a balloon with a note saying it had been released by a bunch of schoolkids in Indiana. I was in Connecticut at the time, so that was pretty cool, but those shortsighted kids hadn’t put any electronics on their balloon, and they kind of left me hanging. So here’s a look at what radiosondes are, how they work, and what you can do to increase your chances of finding one.

Going Aloft

Meteorologists have long known that getting data about the upper atmosphere is critical to accurate forecasts. As early as the 19th century, kites and tethered balloons were used to put recording thermometers and barometers aloft. Limited by the instrumentation at the time, not to mention the length of the tether used to recover the payload, early sounding data was crude at best, but valuable all the same. Free flying instrument packages were also used, with the instrument package returned gently to the surface by a parachute. Unfortunately, with no way to track the package, meteorologists relied on people returning the package before they could process the data.

For the data to make a difference to forecasters, it had to be available immediately. That would have to wait until the 1920s, when electronics technology had advanced sufficiently to allow true aerial telemetry. With a simple package of weather instruments and a radio transmitter, the radiosonde was born.

In the age of the vacuum tube, radiosondes were obviously somewhat chunky, with sensors being mainly electromechanical. Data encoding was often done by an automatic Morse keyer. Battery life was limited, but still, the data produced by these early radiosondes quickly became vital to forecasters, and several companies began mass producing the devices.

Designs have obviously evolved radically over the last 80 years, but then as today, radiosondes are primarily used to measure three critical parameters: air temperature, dew point, and barometric pressure. In the days before GPS satellites, radiosondes relied either on an altimeter or a paddlewheel a bit like an anemometer mounted on a horizontal axis to detect the altitude of the package, critical to the sounding data. Modern radiosondes incorporate a GPS receiver for both altitude data and latitude and longitude, all of which is transmitted back to the ground station. GPS location data not only provides data from a vertical slice of the atmosphere, but also provides data on wind direction and velocity. A radiosonde that provides this information is technically known as a rawindsonde, but that’s such an awkward formulation that the devices are universally referred to as radiosondes no matter what data they return.

Most radiosondes these days are made by one of two companies. Vaisala, a Finnish company whose founder, Vilho Väisälä, pioneered early radiosondes in the 1930s, has a huge share of the international radiosonde market with their RS line. The US National Weather Service had their own, older standard radiosonde that was phased out by 2014 or so by the Radiosonde Replacement System (RRS), and they now favor the Lockheed-Martin Corporation LMS6 for their soundings, although some offices use the Vaisala units.

Twice a Day, Every Day

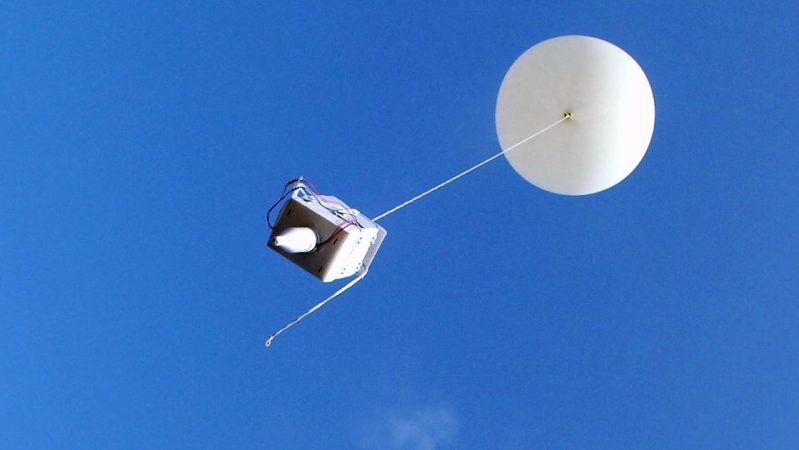

Twice a day, at approximately 00:00 UTC and again at 12:00 UTC, meteorologists around the world prepare a radiosonde mission. The ritual is pretty much the same everywhere, from inflating the balloon with either hydrogen or helium to prepping and attaching the radiosonde. Once released, the balloon quickly carries the radiosonde aloft at 300 m/min on a mission that can last up to two hours and cover hundreds of kilometers. A mission needs to reach an altitude of 7 km to be considered a success, but most missions make it to around 25 km before the balloon expands and eventually bursts as the atmospheric pressure decreases. Altitudes over 35 km are not uncommon, though. The radiosonde continues to transmit data during its parachute descent.

Radiosondes typically transmit either at 403-MHz or 1680-MHz nominal frequencies. Modulation schemes and data rates vary by model, with Gaussian frequency-shift keying (GFSK) being the mode used for most Vaisala devices. Transmitter output power is generally pretty low, in the range of 50 to 100 mW, but getting a line-of-sight signal is not generally a problem after the mission gets a few hundred meters off the ground.

Receiving and decoding live radiosonde data is possible with the right gear. First, check to see if you live somewhere near a weather service office that releases radiosondes. Next, know what kind of radiosonde the office deploys. If it’s a Vaisala, you’re in luck — there are tons of programs out there that will let you use an ordinary UHF FM receiver or SDR dongle to receive and decode data. There’s a complete tutorial on getting started with radiosonde monitoring over at RTL-SDR.com that includes everything from antenna designs to plotting the GPS data on a map.

As for recovering a radiosonde in the wild, it’s certainly possible. Google around a bit and you’ll find plenty of social media posts with pictures of used radiosondes recovered from farmer’s fields or dangling from trees in the woods. Personally, I may be out of luck; while I live downwind of the Spokane, Washington NWS office, it’s only about 40 miles away. I suspect that most missions will go right past me and land somewhere in the vast forests stretching from Idaho into Montana. Chances are slim that I’ll be able to recover one, but that won’t stop me from trying to listen in.

[Featured image source: WNEP.com]

“In the age of the vacuum tube, radiosondes were obviously somewhat chunky,”

At first glance I read “In the age before the vacuum tube”

I was a bit excited to read on and learn just how THAT worked!!

Relays! ;-p

I was thinking about getting the signal back to the surface. Miniaturized spark gap and power source!

There’s been an article about a mostly mechanical weather station here:

https://hackaday.com/2017/10/18/retrotechtacular-weather-station-kurt/

you can find more info on the electromechanical emitter which was probably used in it and also in radiosondes here (in french):

https://web.archive.org/web/20140924002922/http://www.radiosonde.eu/RS01/RS01C75.html

http://www.radiosonde.eu.bonplans.info/RS03/RS03V/RS03V10.html

Even thou it was during WW2, it was still mostly mechanical.

It apparently used a tube to generate the tone but I assume they could have done the same with a vibrator (an oscillating relay https://hackaday.com/2016/07/04/retrotechtacular-dc-to-dc-conversion-by-vibrator/ ), oscillating reed switches…

A very, very, VERY fast motor/engine spinning a generator.

Very very fast motors and alterantors were, in fact, used in VLF transmitters for intercontinental use.

Dad had a radiosonde I think he got at a surplus store. Might even have been C&H in Pasadena.

From what I remember, they used to have contact info on the payloads to have them picked up. One of my old elementary schoolteachers found one and did the “tear it apart cause it looks neat” bit. He managed to misplace most of the parts as well, But he also was found out later to have misplaced a power line and was stealing electricity from the school he lived next to. (pensions are apparently suseptable to theft of services charges)

Once I found a vaisala radiosonde in a field. I didn’t really know what it was but still took it with me. When I opened it I found out it contained STM8 processor, ISM radio and ublox gps chip. It even had the STM8 debug interface exposed. Still on my todo list to hack it.

The location/date the *sonde is found is also valuable to the researchers. It gives them the downwind location which they could not ultimately obtain from the launch.

A department head once asked me to verify the resistance strip inside a *sonde. My Fluke showed it at half of the resistance the manufacturer was claiming. With that knowledge, they were able to compensate the transmitted readings.

I remember adverts for them as surplus in the back pages of zines. I don’t know weather they had flown or not.

I “sea” what you did there!

B^)

You sure took him/her by storm.

Sondes that are dropped from airplanes during research experiments are called,

“dropsondes”! Amazing, huh?

Bears that are dropped from airplanes during research experiments are called,

“dropbears”! Amazing, huh?

Wow! I didn’t know that one!

…and of course chewing gum that is dropped from airplanes during research experiments is called…litter.

Give a hoot! Don’t pollute.

Geesh.

“Candy Bomber” … some nice history.

Several years ago I saw one in a tree a few hundred yards from my home. Had no idea what it was. While I planned an expedition to retrieve it (it was a TALL tree), a storm struck, and the unit came out of the tree and was mostly destroyed when a limb fell on it. Still, I retrieved it, and some quick googling solved the mystery of what it was. Quite an exciting find for my young son and I!

Did you recover the kite my daughter and I lost too?

B^)

It’s not as fun and exciting as finding one. but… you know.. if you really want to tear one of these things apart in person…

they aren’t all that expensive on Ebay. It might even make a good HaD article!

About 25 years ago, each ‘sonde came with a punched paper tape to “characterize” it before launch. The person launching the ‘sonde ran the tape through an optical reader, the individual characteristics of the components would then be adjusted for in the data it transmitted.

I used to work on that tape reader, hated that thing.

We got to witness the switch over of sonde navigation systems, from radio coordination to gps… Our weather guessers and I launched a lot of duds…

I repaired one once, IIRC, the drivers for a couple of the LEDs had died, and some other chip needed replacing.

They are still calibrated individually before launch, by connecting them to their base station and characterising their sensor values versus the ground based ones.

I have a vailasa modern type which was given to me by a friendly radio ham who tracks and recovers them, he has over 70! Mostly from the Launches which take place daily from Kemble airfield near Cirencester , uk. I have listened and can hear them most days so I must try to decode the data.

But I first found one in the early 90s, in a flooded field near silbury hill uk, I has walked up the hill and from the top could see a white mass floating in the water. this mass was the remains of a huge latex weather balloon. The sonde itself was a Much larger device than the modern sondes, it was about 9 inches cubed and quite heavy, It was mostly batteries inside a polystyrene shell from what I could see, And had ‘please return if found’ information recorded on it. I’m not sure if it even had a radio, or just was some kind of data recorder.

I did return it to one of the U.K. Universities and was sent a book token for my trouble.

“It was mostly batteries inside a polystyrene shell from what I could see, ”

Some of the batteries were activated by adding water shortly before launch.

I don’t think they launch from Kemble any more (maybe have not done for many years?). Nowadays in the UK the launch from Larkhill on Salisbury Plain, somewhere in Cornwall near Lands End, Aberystwyth in Wales, Hucknal near Nottingham, and a few others on a less frequent basis.

Most evenings I check the predicted landing spot for them, and if one is coming my way then I will track it. There has been a recent trend of sondes stopping transmitting on their descent, so you cant track it to a final position.

The software you need is call Sondemonitor from a group called COAA in Portugal.

I bought a used radiosonde from the surplus room of Edmund Scientific in Barrington, New Jersey back in the day.

I didn’t know enough to do much with the electronics, but the thing was chock full of mostly good AA nicads!

THOSE powered all kinds of stuff.

I really miss Edmund Scientific. I could browse those bins and have a project created for me from the magical bits contained therein.

Sigh.

I found two, in the space of a month, probably 30 years ago, and haven’t seen another one since then. The first one we found while hiking deep in the santa monica mountains, in a canyon that gets very little hiker traffic. The second one nearly hit me when it fell out of the sky as a bunch of us were doing whatever kid stuff we did. Nobody knew what the hell it was except for me and Brian Donahue, who’d been with me when we found the original and took it apart-we both yelled RADIOSONDE!!! at the top of our lungs when the 2nd one fell.

The units have a little notice on them to turn them in to a postman, when we did it we were expecting a reward, or a pat on the back at least. But the postman just took each one without comment like he’d seen a million of them before.

cw

What a story! Thanks for sharing!

In the Netherlands there is an annual event which involves a weather balloon. Some enthousiasts of Stichting Scoop Hobbyfonds thought it was a nice idea to create a balloon-driven fox-hunt.

Their yearly livestream from the balloon + the QSO’s made by the followers are great to listen to.

This year the balloon actually landed in Germany, it was really nice to see how everything came together in the end.

I found one in the woods near our house when I was in 8th grade. I kept it a while, then threw it away. I didn’t know anything about electronics at the time.

“getting a line-of-sight signal is not generally a problem after the mission gets a few hundred meters off the ground”

Not entirely correct. 1000m above sea level would give you 116km to horizon. So its all about the imposing wind and the climb-rate (and the data bit-rate of course).

IIRC, our scientists sometimes had a problem with the wind moving the ‘sonde out of (radio) range before it reached the tropopause. A fast enough wind, and a low power transmitter…

We found one out in a field when I was probably about 12 years old. It was in a white styrofoam clamshell box, about 12″ x 5″ x 5″, with the two halves taped together and a stiff wire antenna (with a coil wound in it) protruding through the top of the box several inches. This being the 1970s it was all analog circuitry, of course, with discrete through-hole components – surface mount hadn’t yet been invented. The components on the board were not packed nearly as densely as they were in the other electronic devices I had disassembled before, such as transistor radios. I also remember that the entire bottom of the circuit board was plated with a thick layer of lead solder – it did not have individually soldered terminals. Looking back, it was probably an early form of reflow soldering that pre-dated solder masks. Also on the bottom, someone had hand-scribed (with a vibrating-tip etching tool) a short 3 or 4 character code. I believe the device was powered by a 9V battery, but I don’t exactly remember.

I’m pretty sure there was a “please return to” sticker on it somewhere, and feeling vaguely guilty that I didn’t return it to them; but I was way more thrilled to have something electronic that had literally dropped from the sky.

Usually for the pressure + temperature ones they don’t care to get it back. They are not reused anyway. The notice is just there for legal reasons. UV and some other types are expensive and normally reused.

When I was about 12, picked up an unused surplus Radiosonde…. included LIVE parachute eject charge. Was a different time. Back when you could buy saltpeter or full strength ammonia in any grocery store. I just tied a string to eject trigger and yanked it from 20 feet away. No biggie. Don’t recall doing anything usefull with any of the components… save maybe the brass cap.

i want to know, how to spy the hp eye pair because i suspect by him

When Edmond’s Scientific was still in business (Barrington, NJ) they had them as surplus.