Starting a new project is fun, and often involves great times spent playing with breadboards and protoboards, and doing whatever it takes to get things working. It can often seem like a huge time investment just getting a project to that functional point. But what if you want to take it to the next level, and take your project from a prototype to a production-ready form? This is the story of how I achieved just that with the Grav-A distortion pedal.

Why build a pedal, anyway?

A long time ago, I found myself faced with a choice. With graduation looming on the horizon, I needed to decide what I was going to do with my life once my engineering degree was squared away. At the time, the idea of walking straight into a 9-5 wasn’t particularly attractive, and I felt like getting back into a band and playing shows again. However, I worried about the impact an extended break would have on my potential career. It was then that I came up with a solution. I would start my own electronics company, making products for musicians.

I experimented and worked on a variety of projects, sometimes with friends, sometimes alone. After exploring a variety of options, I decided that a simple distortion pedal would be a great product to start with. They’re simple, parts are cheap, and there’s a huge number of ways you can play with the design to create all manner of sonically delicious results. The product would be known as the Grav-A – the first product of my nascent company, Grav Corp.

I Love It When A Design Comes Together

I began the journey by looking to the past, remembering that I’d attempted such a build at the tender age of 18. My former attempt at a guitar pedal was a mess of loose wires, assembled largely with salvaged parts and the meagre selection of potentiometers then available at Dick Smith Electronics (think Australian Radio Shack).

There were serious noise and grounding issues and the pedal only worked intermittently at best. I used this as an inspiration to do better, and threw myself into research.

The Internet is a wonderful resource, and provided me schematics and guides to not only existing pedals, but also the best way to approach striking out on your own. There was a particularly early lesson I learned here. It’s often that people will decry the high price of musical equipment, citing that the average pedal uses only a handful of cheap components. In some ways, this is true, but it fails to look at the whole picture.

A commercial guitar pedal may rely on transistors, op-amps and a smattering of passive components to create its sound, and these can be had for absolute pennies, it’s true. But the pedal’s retail price also has to cover the mechanical components, such as jacks, switches and potentiometers, the enclosure, including paint and printing, the labour required to assemble and ship it, and still leave some room for profit to keep the business behind it running. I quickly realised that it simply wasn’t possible to beat the bigger operators on price, particularly if you’re trying to build a robust pedal that can stand up to the abuse of the average touring musician.

After finding some great resources, I settled on using an op-amp gain stage with a Big Muff-style tone knob with a presence control added. A DPDT switch with centre-off position provided three different clipping diode options – in the feedback loop, output-to-ground, or off. Looking at the rest of the boutique pedal market, I decided to implement a true-bypass footswitch, which, while expensive, ensures that the pedal circuitry can be completely isolated from the signal going to the guitar amplifier when switched off. I also chose to use PCB-mounted potentiometers and jacks wherever possible, as an aid to quick assembly, and as a way to locate the board within the case. The venerable Hammond 1590BB would serve as the enclosure, painted and printed by a US website specialising in small runs of pedal parts. I had a run of 10 PCBs made at OSHPark, in lovely purple, and built the pedal.

From Prototype to Production

The prototype was great and was serving me well on stage, but was too time consuming to build and more fragile than I liked. Particularly egregious was the DC power jack, which didn’t quite fit into the custom machined enclosures. While I enjoyed the pedal and got great feedback from friends, it wasn’t something I could put on the market in its current state, with parts that didn’t quite fit right and artwork that wasn’t dead-on. Another issue was that the the original op-amp I’d used, the LM301, was no longer in production. I resolved to tweak these issues as I moved closer to release.

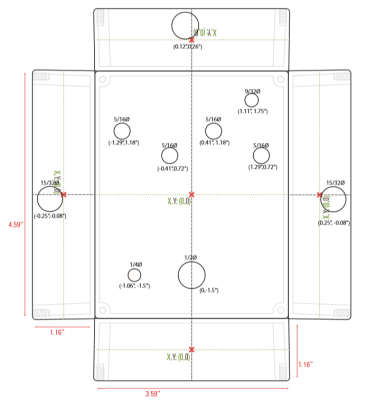

For the enclosures, I decided to switch to a new manufacturer. The initial manufacturer had poor support and used a highly inaccurate template for artwork and machining. Worse, they requested assembled boards be sent their way in order to make the cases fit the PCBs. This may sound like a solid method at first, however making things “to fit” is poor engineering practice, and added two weeks every time I had to ship them a slightly modified board. The manufacturer I switched to instead worked by using accurate measurements from a supplied drawing and the cases came back perfect. Until I tried, I never realised how much trial and error went in to getting the artwork on such a product to line up properly with the internal components and things like knobs and jacks. A total pain, but rewarding once done.

As far as the DC power jack was concerned, I decided to switch to a case-mounted jack, where formerly I had attempted to recreate a modern Big Muff-style setup where the 9 V jack is PCB mounted and clicks into a rectangular hole in the case. This was a major gain, as it made the cases easier to assemble, and the manufacturer found it much easier to drill a round hole than to create a rectangular one.

Other optimizations came in the second production run. I moved both the resistor for the status LED and the switch for the clipping diodes on to the PCB itself. This greatly reduced the number of wires I had to strip and manually solder point-to-point. With all these changes, I reduced production time from 2.5 to 1.5 hours per pedal, estimated.

I begun to implement other techniques to speed production as well. I would take ten boards, and populate them all, then solder them all, then assemble into cases. Batching the operations in stages allowed me to focus clearly on making sure there were as few differences between each pedal as possible, as they were all going through the same production step at the same time.

Headaches

Having pre-orders for the pedal meant there was a time pressure on getting them out the door, which meant I was thrown headlong into the organised chaos that is production. There were lessons that were learned that I hadn’t even remotely expected.

The biggest issue as production ramped up was cosmetic damage. When you’re selling a boutique item for over $150, people expect to receive it in good condition. Having grown up doing projects for myself in my parent’s workshop, my working methods were rough and ready. It was all too easy to drop a tool onto an enclosure or drop a unit on the ground, creating dents, scratches, or paint chips, ruining the finished product. I attempted the dreaded task of reworking these blemished cases, but bar a couple of lucky successes, it was all for nought. This was a huge problem as the cases were costing well over $25 each by the time shipping was accounted for. After dealing with this problem too many times, I revamped my work station, putting down soft foam and organising my tools carefully to avoid inadvertently marring the cases. Simply taking some care in the set up of my work area proved invaluable in reducing these issues.

Beyond that, shipping was a huge problem. Operating out of Australia, I was stuck paying large sums to import both custom and standard parts. These shipping fees added up and made it difficult to compete on price with other boutique pedal manufacturers based in countries like the US which had much cheaper access to components and enclosures. This was also a stumbling block on the customer side as well, as it cost a significant amount of money to ship a pedal out of Australia, too.

Finally, packaging and design issues reared their ugly head. The clipping mode switches were delicate, and a small handful were damaged during transit. The switches would jam up against the side of the box and the shaft would pop out of position when knocked. This was the cause of a couple of costly returns and replacements.

How The Story Ends

Eventually, it became clear that selling a distortion pedal built in one of the farther flung reaches of the Earth was going be a difficult prospect to maintain. It’s certainly not impossible, but the guitar pedal market is flooded with thousands upon thousands of distortion pedals, and thus it is hard to stand out from the crowd.

After fulfilling preorders and wrapping up the second major production run, it became clear that the pedal wasn’t generating a significant amount of profit for the time invested. I slowly began to sell down the last of my stock while developing a second product aimed at a different market. Going through the process a second time, I was well prepared to avoid many of the pitfalls that had struck the first time around.

Overall, I can highly recommend taking an electronic project into production. These skills are ones that are best learned by doing. If it’s your first time, choose a project that’s small, achievable, and one that the market has demand for. Aim on getting cashflow as soon as possible to support your operation, and see where it takes you. And of course, most of all, be sure to enjoy the ride!

I used to dabble in that market. It’s a really tough place to be. Not only are there large companies already making good product at reasonable prices, there are literally hundreds of boutique manufacturers competing for what market is left. You have to design a product that makes a emotional connection that says “BUY ME” to the customer and that is very difficult. Good luck! Remember. The best sales tool is having other musicians see you use it on stage. The grass is always greener on the other side, and you can own your own patch of that green for some cash in hand!

Yeah. It was a great learning experience, but truth be told, I don’t really miss it or have any interest in going back to it.

Sooooo do you have any of the pedals left? I wouldn’t mind one lol.

I believe I do. My supplies have dwindled to just a couple remaining.

I feel like Hackaday and I have a weird dejavu relationship.

As soon as I do a tape release for a friend, Friday Hack chat about cassette tapes.

As soon as I finish a pedal design for a friend, a pedal article.

The coincidences keep piling up, and I’m glad they are. This article is certainly insightful!

@RF Dweeb: We’re watching you!

Cue: Tears for Fears -Every step you take

first and foremost are you in the Pedalboards of Doom facebook group? And second thanks for writing this, I’m in the process of designing several guitar pedals, I’ve been thinking about these circuits for a few years finally going to design some boards and make pedals. Will be looking back here if any of my designs are worth bringing to market !

For marketing there is mainly utility, perceived scarcity, and novelty.

Utility: Does your device do something useful? or will a pencil though a speaker also work

Perceived scarcity: Is the market saturated? than a small production run will not be lucrative

Novelty: Is th product unique? or does it look like its from Ali-express from the consumer’s perspective (an innovative design will buy you about 3 months of sales)

Design pricing (Capitalism is dead, but geed is alive and well):

Ask yourself if you are you competing with $4.37/hour China/India production-line labor? Sure the customer will love a deal, but trust they won’t care if you and your family go bankrupt. More importantly, desperate manufactures must keep the factories running something — some will clone or outright steal anything to stay in a profit mode, and this global issue is especially pronounced in places with heavy industrial-espionage/citizen-surveillance-laws/douchebag-hackers. It doesn’t matter if a product is high tech and you requested the FCC seal your design files, as the financial barriers to market entry by your competitors are simply a math problem based on sales estimates.

Keep your mouth shut, and your ego in check:

Stay off the Internet for as long as you can, as statistically there is always some crazy person that thinks these rules won’t apply to them (Hack a Day is famous for things like $9 computer plans). By talking with people relevant to your business,,, you gain a clearer picture of what people want, and how they perceive your products. You should only care about your Paying-Customers, and should actively avoid as much of the vampire kit markets as possible. In reality, many people are obsessed with their narcissistic on-line persona, so they never even look up from their phones in public.

The ego part is a warning not to let friends/family/employees/dumb-ass-Internet-kids try to manage your risks for you. The fact even Intel said its going to expose itself to more risk is laughable — given none of the opinionated will suffer the consequences of failure.

Don’t try to do it all yourself:

Or put another way, have integrity even when people wrong you — your image within society will determine how people form trust around your brand. If you act like countless other bottom-feeders running startups, than your success rate is 1 in 24 (and the board will fire you eventually anyway). Chances are you are not a lawyer or corporate financial accountant, and I can’t tell you how many clowns I’ve seen shifting focus away from generating revenue to argue with experts — and even their own hires.

Don’t debt-finance (or give credit):

These often are offered as predatory short-term loans, Venture capitalists, and rolling credit lines. Unless the inventory is already pre-sold you shouldn’t even be running the line. You can get stuck bleeding money acting as a contracted-warehouse for some scumbag retailer.

Revenue:

This is the most important metric of whether you are a business person, or a delusional sucker.

Do you actually have a reasonable customer base, sales list, and move significant product?

I am not saying building a sales base for a brand is easy or cheap — but if you are paying yourself less than a real job it is not a real business.

Most amateurs cap off at about $90k/year profit, and it seems independent of the number of hours they put in — at that point you need to hire someone that actually knows how to run a business.

Karma:

Being useful is good and profitable to both yourself and others — If your supply chain is healthy — you all do well.

Taxes/Law:

Remember point 4, and talk with these people >>before<< you start spending money or signing things. A good accountant will always make more money then they cost, and a good corporate lawyer will save you from losing your hard earned money later.

LOL,

Keeping it real with tough love I see. I think you may have scared them (and me for that matter). Where did you get your experience on this? Good tips.

#5 – No VC either? Maybe depends on the need, but what if the trade is for interest in the company only (not a loan)? I did get similar advice from Mark Thomas (Founder Right Hemisphere). He said “grow slowly” (assuming there’s no race to the top).

#2 – Not sure what you’re suggesting… Build offshore for $4.37/hr, but then they’ll steal your product anyway?

Cheers.

Wow! 18 years ago when I was in China, the average wage there was $0.25 USD / hour. Their wages have gone way up!

I am not in the Facebook group, I’m not big into pedals at this point.

I’d say a lesson I learned was from looking at a particular digital pedal posted on Hackaday. Truly unique and with beautiful design. It had people throwing money at the screen, but remained a small runs pedal due to hand assembly.

as a hobbyist being in e very relaxed situation i think i can comment for these buyers: my pedalboard has only 4 pedals on it and i really dont need any more except maybe one. currently there is a zoom g1on multieffect on it, a mooer compressor, a cheap chinese equalizer and a cheap chinese ocd clone (by far the most important pedal here).

the only pedal i will build in the future is something built around a chinese analog devices 1701 dsp board. nothing more. if you can build multi fx pedals- those sell i believe because a lot of customers think they are no pros and in need for specialiced stuff. if i want to try out 2 tubescreamers in the chain i simply dial them in on the g1on.

A CIA report said onky the US & 2 other countries don’t use metric, and ~2 of them are lying. I grew up Imperial but use metric easily. But why sid YOU have to use inches?

Many of the foibles you learned are commonly known. Network. Beg aomeone to visit and give for a few hints for the cost of a good meal (which gives you one more hour w them. Personally, I love a small startup. Your case damage – expoxy paint in a splatter shoot pattern. A Q-tip dabs out assidents. Dab. Got that?

The best available case manufacturer that works in the small runs I needed was using inches, so I used inches.

Why don’t you try using only half of whatever you are on.

I just use a computer running Ubuntustudio and Rakarack. 40 pedals of many sliders and settings of goodness. Free.

I would like to see a version loaded with presets running on a ‘pie or something without a screen etc.

You could spend the $12 on a USB adapter, and do the software yourself.

I canceled a very similar project after looking at the saturation, licensing issues, and team skill set.

One guy is still living the dream with 2 sales a quarter if I recall…

Note, a $100 laptop PC comes with it’s own battery, sound banks, and high speed network options. ;-)

Fun read. “True” would be my comment.

Lewin Day says:

“Thee best available case manufacturer that works in the small runs I needed was using inches, so I used inches.:

You are in Australia so I thought you case mfr would be also. If so, he already has a pipeline he could tap you into for piggyback shipping. Too late in any case… :>/ It does fill your resume impressively however! Even US – UK shipping is ridiculous for two close (and proximate) allies.

Lewin,

No matter what happens, how big or small, it’s the journey that counts. You’ll learn so much that will help with everything in life, especially if you get into Mfg or Engineering.

I’ve got my own startup and I keep getting tested in the most difficult ways. It’s like Tesla Stock, you just have no idea when/if it’s going to pop! But the experience almost landed me a job at Fender as a Pedal Designer last month – 2 interviews at VP level. Just means I have more to learn is all.

Best of luck and success!

Sorry this is a bit belated, but on your pedal to production project, your graphics looked great, very clean. What graphics design program (and templates) did you use for the artwork and drill templates? I have been doing it for a while in inkscape. I am always looking at ways to improve. Any thoughts on graphics tools to use would be appreciated! Mark@frogpedals.com

Yeah, just Inkscape and my personal taste!

My band has just received a ‘signature’ branded chorus pedal, designed and hand-made by a friend. Some of our fans have expressed a desire to buy one, but having each unit hand-built would be way too time consuming and expensive. So we’re looking to get a small run – maybe 10 to 30 units – commercially manufactured. Would you be able to share the names of the manufacturers you used? We have all the schematics, art etc. 100% ready (from the prototype). Any input/advice would be much appreciated!