In July 1940 the German airforce began bombing Britain. This was met with polite disagreement on the British side — and with high technology, ingenuity, and improvisation. The defeat of the Germans is associated with anti-aircraft guns and fighter planes, but a significant amount of potential damage had been averted by the use of radio.

Night bombing was a relatively new idea at that time and everybody agreed that it was hard. Navigating a plane in the dark while travelling at two hundred miles per hour and possibly being shot at just wasn’t effective with traditional means. So the Germans invented non-traditional means. This was the start of a technological competition where each side worked to implement new and novel radio technology to guide bombing runs, and to disrupt those guidance systems.

Finding a Runway is Like Finding a Bombing Target

For the first four months of the campaign, Germany used a guidance system called ‘Knickebein’. This translates as ‘crooked leg’ and allegedly was derived from the shape of the transmitting antennas. In 1940, radio navigation was decades old technology and in wide-spread use. The Lorenz system for example was a landing aid that allowed pilots to precisely line up with a runway from as far as 30 miles away. Such systems were in international use since the mid thirties.

by Anders Dahnielson CC-BY-SA 3.0

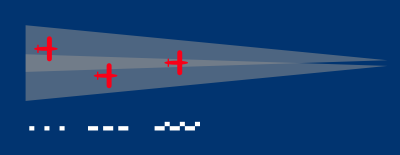

Lorenz beams works by emitting narrowly focused radio signals from a set of antennas positioned perpendicular to the runway. An approaching pilot would use his radio to listen to the signal that consisted of short tones with longer pauses (dots) when lined up to the left of the runway, and long tones with short breaks (dashes) when off to the right. When lined up with the runway, the pilot heard a continuous tone because the dot and dash signals overlapped in the middle. The system was easy to use and the required equipment was cheap, or even already in place, so it spread quickly.

Knickebein was little more than two Lorenz beams turned to eleven. The base stations were more powerful and the beams had a narrower focus, but the principle was the same. Two stations were used to mark a bombing target by intersecting their beams over it. A bomber crew then flew along one beam and dropped their bombs when they crossed the second one.

[Image source: pa0pzd.com]

The test flight that proved the existence of Knickebein almost didn’t happen. Since airplanes were in short supply the hunt for the signal took place from an old training aircraft that was just about to be decommissioned. The plane had no suitable radio on board and was fitted with an American made amateur radio receiver from a shop in London. On June 21 a successful flight received the signal and proved long-range use of Lorenz was possible. Reception worked because at the operating altitude of a long range bomber, the horizon is far enough away that it becomes possible to pick up high frequency signals from across the Northern Sea.

Straightening The Crooked Leg

The British had figured out how the Germans were guiding their bombers and needed an immediate solution to put a stop to it. An obvious option would be jamming the signal, but the required radio transmitters to accomplish such a feat were hard to come by. The newly founded electronic countermeasures unit hit it off with a hack. The head of the unit learned that medical diathermy machines — used for high-frequency therapeutic heat — operated in the same radio band as Knickebein. The machines were commandeered from hospitals all over the country and moved into the paths of the beams when a raid was imminent. The diathermy sets produced a lot of radio noise that suppressed the beams. More sophisticated methods were developed soon but the repurposed medical equipment provided critical first aid.

Later on transmitters that broadcasted ‘surplus dots’ were rolled out. They caused great confusion among the attacking aircrews and succeeded in throwing them off their tracks. The effort to render Knickebein useless culminated in synchronizing the decoy transmissions with the German signal to ‘bend’ the beams and move the bombings away from their intended targets.

Whether or not these surplus dots were actually used is up for debate. Wikipedia says yes, while the person in charge of the operation has given a BBC interview in which he reports that the capability was in place but never used for unrelated operational reasons. This didn’t really matter because by now the Germans had realized that Knickebein had been rendered useless and came up with a new idea.

Fooling a Fully Automated System

The successor was the X-Gerät or X-device. On the transmitting side it was little more than a more elaborate version of Knickebein. X-Gerät again used one Lorenz beam to set the bomber’s course and then three cross beams to time the drop. Early British countermeasures consisted of emitting surplus dots as before, which this time showed little effect. The reason for this may have been arrogance. When analyzing the German signals, the modulation frequency of its tones was wrongly measured as 1.5 kHz. The correct frequency was 2 kHz. When the error became known, the British considered it irrelevant, assuming that a radio operator in a noise plane would be unable to tell the difference.

It took them several weeks and a downed German bomber to realize that with the X-Gerät there was no radio operator involved. The system used an optical indicator to keep the plane on track and an electromechanical calculator to automatically release the bomb load. These units featured electronic filters that completely removed the surplus dots from the received signal. With this new understanding, the surplus dots could be brought to some effect.

It took them several weeks and a downed German bomber to realize that with the X-Gerät there was no radio operator involved. The system used an optical indicator to keep the plane on track and an electromechanical calculator to automatically release the bomb load. These units featured electronic filters that completely removed the surplus dots from the received signal. With this new understanding, the surplus dots could be brought to some effect.

Additionally another system was rolled out, the ‘False Elbe’ (the four beams used by the German side all bore the names of rivers). The time between crossing the last two, ‘Oder’ and ‘Elbe’ signals set the bomb timer. This was fully automated, allowing no human override. So to protect the high value targets, the British operated their own station that projected a beam that would be interpreted as the ‘Elbe’ signal right behind the ‘Oder’. The result was an early drop and a thoroughly plowed countryside just south of Britain’s industrial centers.

What’s In a Name?

At this point it became clear that approaches based on Lorenz beams were obsolete. The Germans had to come up with a completely different solution. While the system was officially designated as ‘Y-Gerät’ this pinnacle of creative naming didn’t sit well with the guy behind it, so it also got the code name ‘Wotan’. This information leaked to the British and the fact that Wotan was another name for the one-eyed god Odin made them suspect that Y-Gerät would work with just a single beam instead of several like its predecessors did.

The Y-Gerät was superior to Knickebein and X, in that it did not reveal the location of an intended target before a raid took place. On the other hand it was unable to direct a large number of planes at the same time. Also it was doomed from the beginning. Having gained understanding of the new system beforehand, combined with sheer luck, the British were able to mess with Wotan from day one. The carrier frequency used by the other side coincided with the one of a TV broadcast station that had been mothballed when the war broke out. To counter Wotan, the British transmitted their own responses when they received pulses, slowly increasing the transmission power over time.

With the system being new, the resulting inaccuracies were blamed on teething problems and lack of training. Not knowing that Wotan was being jammed, aircrews and radar operators accused each other of incompetence. The Y-Gerät was the last bomber navigation system the Germans brought to bear in the Battle of Britain.

“Whether or on this was actually used is up for detabe. this was actually achieved, is unclear.”

???

“sentence fragment” is also a sentence fragment.

Oof, I’ll take credit for that abomination since I did that in editing. Not sure why that thought became so mangled but it’s fixed now. Thanks!

> ” abomination…? ”

Really…?

Was that a Freuduan slip or just a lapse in general?

(Don’t answer. You’ve taken enough of a beating already…

Or, No – I won’t say it. The others must all be Brits and too

mannerly to mention this… choice of description. Heh heh.)

What is “detabe” used for ? :-)

He may have forgot the capitalization and hyphen. DEB-ATE

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-24018-3_7

B^)

Doh! DET-ABE

The grammar nazis attack ! we got jammed ! :-D

Sorry but I’m with them on this one. Messed up punctuation and minor misspellings can be overlooked, most times without the reader actually noticing, but this was a bit painful at parts. I had to stop reading part of the way through even though it was an interesting topic.

Coming soon!

A new Julia Roberts movie, “Beeping with the Enemy”.

B^)

“Gone with the beep”

Beep, Beep, I’m a Sheep

With Bob Marley’s “Jammin'” on the soundtrack?

B^)

check out “The Wizard War” by R.V. Jones, a fascinating account of the lesser known technological back and forth battle in the airways over the English channel.

The same author published “Most Secret War”

This might just be the British version of the book you suggest.

+1 An excellent read.

(and yes, they are the US/UK titles for the same book)

Yes, I read it about thirty years go. I don’t remember much of it now, but I was impressed with it at the time. I think some of my impression was because it showed how they gathered information, and then interpreted it, They were getting raw information, made guesses, which steered them towards specific other bits. “Hacking”, to use an overused word, they had to uncover information rather than have it handed to them.

I guess I should reread it.

Michael

Hmm, for some reason reminds me of pigeon guided rockets.

The Finns jammed Soviet radio mines during WW2 by playing a complicated melody 24/7 on the radio frequency. The bombs were triggered by three particular tones in sequence, so the music either set the bombs off prematurely, or masked the trigger transmission. When the transmission frequency for the bombs was discovered, one of the national broadcasting company radio vans was hastily commissioned to the front lines and the record they happened to bring along was a popular polka. The record was played 1,500 times over until they could bring along better jamming equipment. Imagine sitting there moving the needle back every three minutes.

This was the record:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gZx1zl_sVTI

In US Army radio school, I was told that bagpipe music played constantly over the enemy frequencies may induce them to surrender! B^)

I thought bagpipes were prohibited under the Geneva Convention.

On a slightly related note, Terry Pratchett’s Nac Mac Feegle clans have a member called a Gonnagle who’s job is to play the bagpipes and recite (bad) poetry at enemies.

Bagpipes would make anyone surrender, even loose the will to live.

Where does the will to live go after you’ve set it loose?

How do we know, after all it is lost.

Oh dear …. that was good :-)

Not that likely, people are like cockroaches – they can tolerate almost anything!

In regard to that polka and the story behind it, it could be updated to include an explosion at the end of several stanzas, sort of like the cannon fire in the 1812 Overture.

Far Side Comic “welcome to Heaven here’s your harp” second panel “welcome to Hell here’s your accordion”.

I just captured that lively polka to play for our street fair.

If there are any Russians ‘listening’ in right now, here’s a blast from the past to jam to.

Interesting to see the bayon style keyboard in the picture, it’s way too good for the rest of us westerners hobbled with our archaic keyboard.

Ha! Polka, my new favorite weapon!

Get rid of the death penalty, and go straight to prisoners choice of either Polka, or Bagpipes.

B^)

BTW, the idea behind the Lorentz beams is still being widely used – e.g. the ILS landing system or even iRobot’s Roomba when it tries to find its charger (using infrared LEDs instead of radio).

Or the AN ranges widely used in the US until the 1960s…

Allied bombers at one point used the tones from widely dispersed stations to signal when they were over target. AIUI, It was more of Beat Frequency Oscillation instead of discrete beeps.

using am stations as an early nondirectional beacon (ndb) and tracking them with an early version of an automatic direction finder (adf).

Now we post bombarded with Rammstien du hast et.al. trauma: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W3q8Od5qJio

Edit, typo: “Now we’re” instead of “Now we”. I think the handlers jammed my thoughts again… wonder if they’re Germanic?

Considering that English was a later derivation of German, it’s possible!

B^)

Too bad English didn’t inherittheGermanuseofruntogetherwords to make anewword!

B^)

Too bad, it prevents us from having cool names like Hackaday.

Interesting read on the radio beam guided raid on my home city, Coventry, which was always rumoured to have been preventable, albeit at the risk of disclosing to the Nazis that we could jam their systems: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=yq6YCgAAQBAJ&pg=PT76&lpg=PT76&dq=coventry+lorenz+beam&source=bl&ots=ptAV9xAoSe&sig=dhYXtR1apYZmGCGMa4wB8TH1oro&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiK85n1oMLaAhWIAMAKHT2BCzYQ6AEIUzAE#v=onepage&q=coventry%20lorenz%20beam&f=false

Hmm…

I’m fairly sure I read in Turing’s bio that it was preventable because of enigma being cracked, and that’s what they didn’t want to let slip?

The same problem could be found on multiple fronts; if you suddenly flip from being vulnerable to an attack, to invulnerable, the attacker knows you have countermeasures and starts on a plan B. You need to ramp over time to make it appear as ineffectiveness or incompetence.

(For me, the most entertaining counterintelligence was creation of the myth that carrots are good for night vision, to try to mask the huge advances in radar brought about by the invention of the cavity magnetron. 75 years later we’re still telling kids it’s carrots.)